[Reader warning: This is a wonky post that is aimed at people who have read Climate of Contempt or who otherwise have a deep and granular understanding of how electricity markets work.]

——

Chapters 3 and 5 of Climate of Contempt discuss expert disagreement over which electricity market structure will best facilitate the energy transition: competition and market pricing, or price regulation and monopoly provision of electric service? This is a complicated question that may have no right answer.

The Cliff’s Notes version of that discussion is as follows: traditional price regulation tends to incentivize building generation reserves, which enhances supply reliability but can lead to overbuilding and higher rates. And monopolies have incentives to impose barriers to entry for new technologies like wind and solar generation. Price competition, on the other hand, exerts downward pressure on costs and prices, and often comes with low barriers to entry, both of which can favor cheap, easy-to-build wind and solar farms. But competitive markets tend to undersupply generation reserves (absent government intervention) and sometimes fail spectacularly in ways that impose huge costs on customers and other market players. The uncertainty that market pricing entails scares politicians and investors alike.

Two 2024 court decisions illustrate this dilemma. In June 2024 the Texas Supreme Court upheld state regulators’ decision during winter storm Uri to raise wholesale power prices to $9000/mwh for 72 consecutive hours, a decision that cost Texas ratepayers more for power those three days than they paid for power during the other 362 days of the year combined, and one which many experts criticized. And in February the D.C. Circuit approved a decision by NYISO (a competitive electricity market) to tweak the formula by which it acquires reserve generating capacity in ways that will impose an estimated $100 million in costs on New York ratepayers.

For students who are trying to develop a deep understanding of this “markets vs regulation” debate, the task is difficult enough on its own. It is made more difficult by the fact that much of the information they encounter comes from advocates of one institutional structure or the other. Nor is it as simple as “Republicans like markets and Democrats like regulation.” Rather, people of all ideological stripes seem to develop strong, conflicting beliefs about these issues, even within partisan and ideological groupings. Regrettably, this group includes experts who sometimes put advocacy before education in their public remarks.

That means learners must sample a variety of perspectives. One way to do that is to read the scholarly work that I cite in chapters 3 and 5 of my book. Another is to seek out news and analyses from multiple and varied sources. And generally, reading long form news and analyses is the best way to do this. Usually doing so will cure the careful learners of their certainty that this or that market structure is unambiguously best.

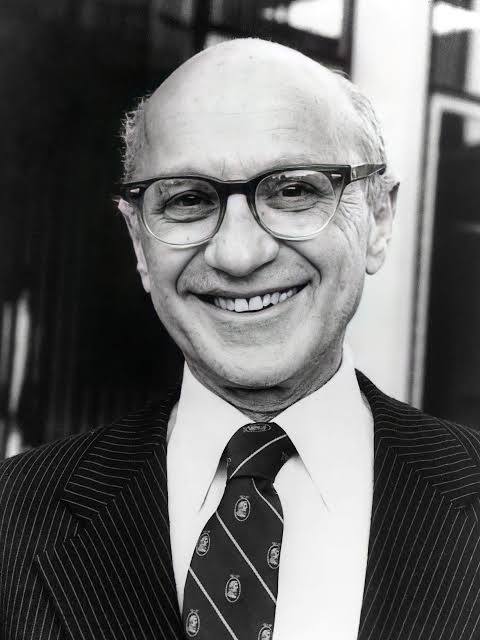

But if podcasts are your thing, consider as examples two podcasts from earlier this year that dive into this question of whether market competition or government leadership is better for the energy transition. The first is Bryan Lee’s conversation with R Street Institute economist Michael Giberson on Lee’s Energy Markets Podcast.

In addition to his affiliation with R Street, Michael Giberson has taught at Texas Tech University and runs a website called “Knowledge Problem” with Lynne Kiesling, on which both explain why they champion competitive energy markets. Giberson (like Kiesling) is a careful academic economist, and in his conversation with Lee he responds to the host’s leading questions using careful language, asserting only what the academic research supports and no more.

Lee seemed to want Giberson to endorse the notion that competition brings lower prices consumers and more renewables for energy transition advocates — full stop. But the story is more complicated than that, and Giberson said so. Which is why it is worth a listen.

The conversation also revealed some interesting numbers about how much less expensive electricity is today (in real terms) than it was 40 years ago, and the reasons for that. And Giberson allowed that while he may suspect that competition is lowering retail prices more than in regulated jurisdictions (all else equal), that is a difficult proposition to prove.

The discussion also included an interesting claim (endorsed by both host and guest) that only the Texas ERCOT market really “quarantines the monopoly” — prohibits monopoly utilities from undercutting other market participants — in ways that create fair competition among electricity suppliers. Giberson and Lee singled out states in which the old monopoly supplier is responsible for providing service to customers who have no other options or who simply chose never to switch suppliers when markets restructured. If that (subsidized) service is inexpensive, this arrangement discourages customer switching.

It was a fascinating discussion of the merits of competition and market pricing of electricity, one from which energy policy students can learn a lot.

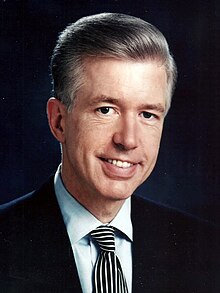

The second example is David Roberts’ conversation with geographer Brett Christophers on Roberts’ Volts podcast, and it is every bit as interesting and illuminating as the Lee-Gilberson conversation. Christophers is an academic geographer at Upsala University in Sweden and author of The Price is Wrong: Why Capitalism Won’t Save the Planet. His book takes aim at the inference that because renewables are now the cheapest form of electricity generation on a levelized cost basis, market competition will facilitate their rapid growth.

The gist of Christophers’ argument is that while renewables are cheap, their growth is slowed by the fact that they are not as profitable as natural gas-fired generation. He offers three basic reasons for this. First, because natural gas usually determines the spot price of electricity (see chapter 3 of my book), when natural gas prices decline that decline drives down electricity revenues for all generators. When that happens, natural gas plants — and only natural gas plants — experience a simultaneous drop in their variable costs (the cost of the gas they burn). Second, because natural gas plants can provide power during whatever time of the day or season power is most needed and valuable, they are better equipped to thrive as volatile electricity markets evolve. Third, because wind and solar are built far from load (where land is cheap) they bear higher transmission interconnection costs than fossil fueled plants, and those transmission costs are omitted from the LCOE estimates that make renewables look cheaper.[1]

All of these problems, says Christopher, make bankers wary of financing renewables. The continuing growth of wind and solar, he says, owes more to government subsidies than to their low costs.

The Volts conversation dives into each of these points in relatively clear and understandable ways. There are rejoinders to Christophers’ arguments, almost all of which Roberts raises. Under questioning Christophers qualifies his claims a bit. And in the end, the listener comes away with a deeper – and (appropriately) less certain – sense of how these very real dynamics will drive the energy future.

Indeed, policymakers may respond to the problems Christopher identifies differently in different places. In blue states, regulators may decide to provide price certainty for low-carbon generation (renewables and firm generation), while red states may allow natural gas plants to exploit the advantages Christophers’ identifies in order to retain or grow their market share. (Or, as in the case of my home state of Texas, they may actively put a thumb on the policy scale to subsidize natural gas-fired generation in their “competitive” market.)

The point is that taken together, these two podcasts provide a fuller, richer picture of the how different market rules influence the energy transition than either could alone. Sampling information from different ideological buckets in this way is a good preventative for the kind of premature certainty that can close one’s mind to complexity. These sorts of deep dives into the relationship between governments and markets lay bare the faults of oversimplified anti-government or anti-market philosophies. Most experts agree that governments and markets need one another; they only disagree about how that reciprocal dependence ought to play out in policy choices.

So when you encounter claims that challenge your prior beliefs, be curious, not judgmental. Steer away from online forces that urge you to ignore or disbelieve part of the truth. Try to find the deep, comprehensive, journalistic treatments of energy transition issues amid the sea of “advertorials,” press releases, advocacy journalism, and misinformation. Go find “the other” side of an issue you care about, so you can understand it more deeply. Savvy learners need to be multi-directional. – David Spence

—————–

[1]This is not precisely true. It is true of the widely-cited Lazard LCOE estimates, but not the Energy Information Administration’s LCOE estimates. The EIA data includes estimated transmission costs for each generation technology. And consistent with Christophers’ claim, those costs are three to four times as high for wind and solar as for natural gas.