Why can’t we be transparent about tradeoffs?

The task of delivering power that is reliable, affordable, and clean is complicated. Anyone who wants to understand it can do so, but they must travel along a lengthy learning curve. When you get far enough along that curve, you develop a fuller appreciation for the tradeoffs involved. However, throughout the journey the temptation to assume away those tradeoffs in service of some urgent policy or political goal is strong.

Nevertheless, the tradeoffs remain. So, the more transparent we are about them, the more likely we are to generate durable political support for the balance we want to strike between reliability, affordability and environmental performance.

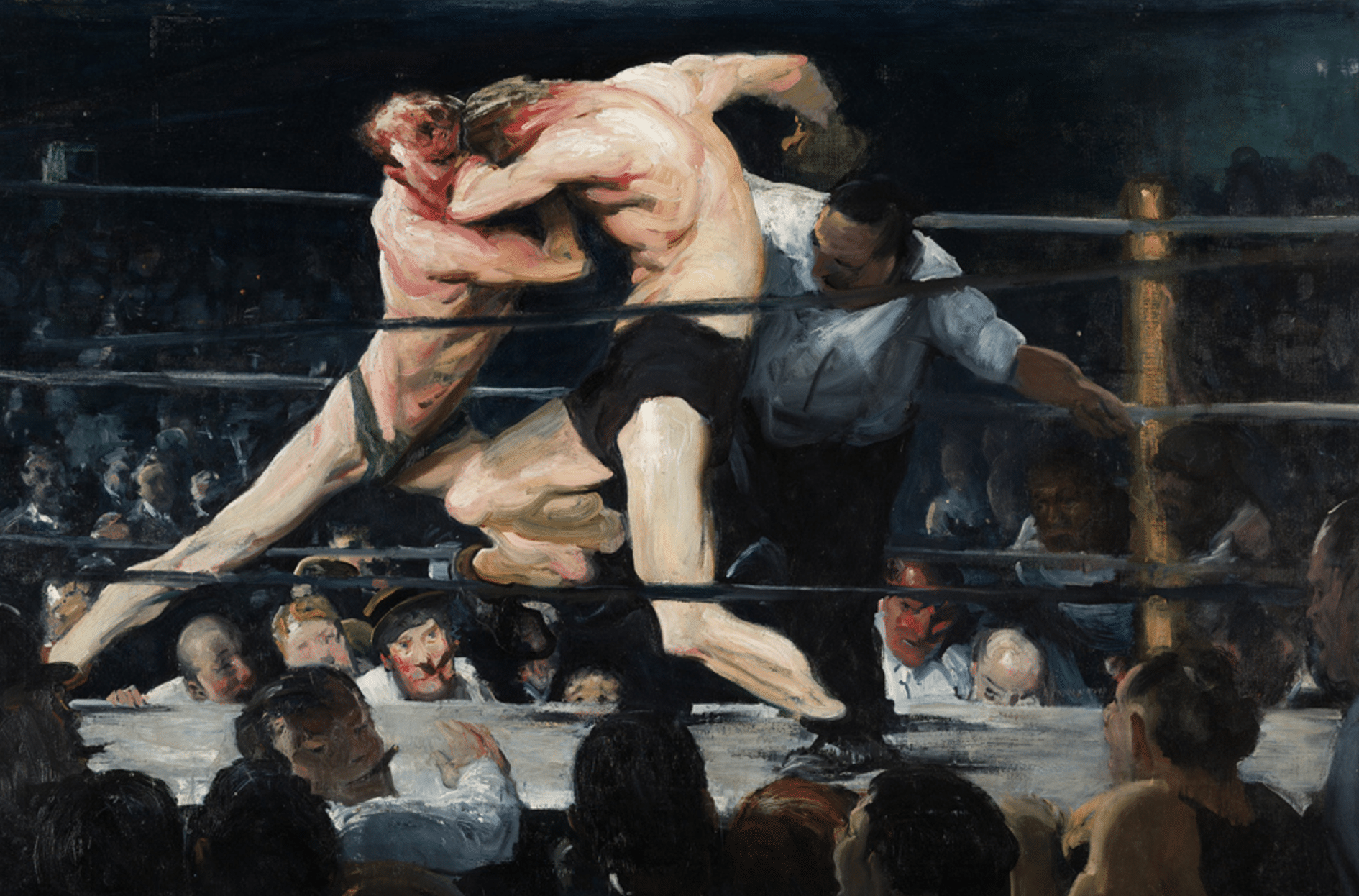

Reasonable people can differ over what that balance should be, but strong feelings tend to inhibit open-minded, respectful discussion of electric grid issues — particularly when the pace of the energy transition is implicated. To many, that particular policy conflict feels like war, and truth is often an early casualty.

So it has been with public discussion of two recent energy policy stories: (1) blue states’ reconsideration of generous net metering compensation schemes for rooftop solar energy, and (2) the recent massive blackout on the Iberian Peninsula.

Net metering reconsidered

The states of California and New York are reconsidering the way they compensate homeowners who send excess power from their rooftop solar units to the grid. Like many states, California and New York have compensated rooftop solar by subtracting the amount of power they send to the grid from their monthly power consumption — that is by “netting” their retail consumption – and paying for the net amount at the applicable retail rate. This is what is meant by the term “net metering.”

States like California and New York are backing off of this idea for two reasons. First, from the grid managers’ point of view, it is expensive. Wholesale rates paid to utility scale solar producers are often much lower, anywhere from 1/3 to 1/8 of the retail rate. When enough rooftop solar units are compensated at the retail rate, it can push everyone’s rates higher. Or at least that is what these two states have concluded.

A February 2025 analysis by the California Public Utility Commission identified net energy metering programs as one of “the biggest drivers” (along with wildfire-related costs) of higher rates, which is why the state is looking to change the way of compensates rooftop solar owners. And the New York Public Service Commission recently altered its compensation rules for rooftop solar, citing “affordability concerns.” (Advocates of a more decentralized electricity system dispute these conclusions.)

Second, in places where grid operators rely on power sales to cover all or some of the costs of maintaining the grid, net metering shifts some of the fixed costs from rooftop solar owners to other customers. Since rooftop solar owners tend to be economically better off than the average customer, net metering can be a regressive cross-subsidy in that situation. The California report cited above mentioned this concern as well.

This is a decades-old and hotly-contested argument (see e.g., here, here and here), which may be why the combatants have difficulty acknowledging both the tradeoffs involved and that reasonable people can disagree about those tradeoffs. This primer, however, illustrates that these concerns exist and need to be acknowledged.

In chapter 5 of Climate of Contempt I summarize the views of people who advocate a more decentralized grid, one that shifts power and responsibility for ensuring a reliable, affordable electricity supply away from utilities and toward customers. They believe sincerely that their vision is realizable, and they could turn out to be right, or not. Either way, realizing that vision is extremely complicated, and entails change that some oppose. Many of those opponents are neither stooges of the utility industry nor opponents of the energy transition. But the intense feelings on both sides of the issue divide make it difficult to discuss all of that complexity respectfully and honestly.

The Iberian power crisis

The recent outages on the Iberian Peninsula offer another example of the way, complicated power sector developments become instantly weaponized in arguments over the energy transition.

When power came mainly from plants that relied on spinning turbines — e.g., coal fired power plants, hydroelectric facilities, and nuclear power plants – grid operators counted on “rotational inertia“ to soften the impacts of a sudden loss of power from a plant. The grid must maintain frequency within a narrow range (50 Hz in Europe, 60 Hz in North America), and a sharp, unplanned change in supply or demand can threaten that. Because turbines keep spinning after a plant stops burning fuel (or splitting atoms, or running water through the turbines, etc.), that continued rotational inertia smooths the effect of the shut off, making it gradual.

We have long known that non-rotational resources like wind and solar have the capability of mimicking the “smoothing” effects of rotational inertia – a/k/a “synthetic inertia.” Given the right incentives they can and will do so. Other measures, like adding fast-response resources (batteries) and so-called “grid forming inverters,” can also help. The Texas grid, for example, has a lot of variable renewable power and lots of batteries and synthetic inertia available when rotational resources are low. Spain’s grid may have been short on all three things: rotational inertia, synthetic inertia, and batteries.

But that doesn’t mean that we ought to be complacent about the continuing technical challenges of moving to a low-carbon energy system. “We can do it!” is not substitute or open discussion of the new challenges the transition presents. In the long run, transparency is the best policy, even for those who are lobbying others to get on board with their preferred policy.

The recent outage in the Iberian Peninsula reportedly involved a sudden frequency shift in one location, which in turn triggered a cascade of automatic shut offs across the larger grid. Some grid officials initially blamed the lack of turbine-based rotational resources online at the time, which led critics to blame renewables for the outage. Champions of renewable energy dismissed that as irrelevant. But we won’t know exactly what happened until detailed post mortem studies are completed.

That hasn’t stopped online policy combatants from framing the crisis to fit their policy views and impugning each other’s intelligence and character. For example, when renewables critic Roger Piehlke blamed “instability” caused by high penetration of solar on the Spanish grid, a pro-renewables consultant (on an email list to which I belong) chalked up Piehlke’s views to the Dunning-Kruger effect.

It is simultaneously true that (1) the presence of more variable resources complicates the task of balancing supply and demand as rotational resources exit the grid, and (2) that problem is likely solvable using existing technologies. The transition does present new challenges as variable renewables replace less variable, rotational resources. We are traveling along the learning curve. Replacing those exiting resources with synthetic inertia and batteries may entail higher costs, though we don’t know that yet either. Some grid engineers question the viability of those solutions; others are more sanguine about solving this problem. The few sober analyses that followed the incident (like this one) emphasized all this uncertainty.

Engineers will learn from this. That learning will add new data to our understanding of the tradeoffs between getting to net zero, keeping the lights on, and doing so affordably. It’s just too bad that so many policy warriors use these events to lobby rather than to learn. It would be better if they could step out of their bunkers long enough to wait for the lessons, and to use them in a more civil and substantive debate about how we want to make the tradeoffs inherent in the transition to a lower carbon future.

In the bitterly partisan world of social media, too many people come to certainty too quickly. And certainty is the enemy of learning. – David Spence