This year’s gerrymandering wars are a predictable consequence of the forces that are driving our political polarization: not the bogeymen imagined by populists on the left and right, but rather the amplification of the angriest, most ideologically extreme voices by partisan sorting, ideological news, and social media. These forces combine to cultivate the growth of ends-justify-the-means politics that is undermining respect for pluralism, truth-seeking, and fair competition. Those are core values on which our constitutional design depends.

Here is what I said about this problem in Climate of Contempt:

[A]ntiliberalism (or illiberalism) is on the rise in political discourse, particularly online and most alarmingly among political communities that openly support authoritarian ideas. Republican megadonor and Donald Trump adviser Peter Thiel has said that he “no longer believe[s] that freedom and democracy are compatible.” Some American conservatives now openly express their affinity for a more authoritarian form of government, and for autocrats like President Viktor Orban of Hungary; indeed, the influential Conservative Political Action Conference invited Orban to address its annual gathering in 2022. The state legislatures of Wisconsin and North Carolina have been particularly transparent in their attempts to enshrine minority GOP rule in their respective state governments through gerrymandering and various other legal maneuvers. These developments, in turn, provoke on the ideological left anguish and fears of transitions to “fascism,” which are then dismissed as hysteria by some on the right. This self-feeding cycle of growing centrifugal forces whirls ever faster.

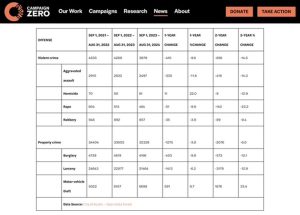

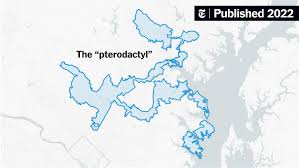

Nobody likes gerrymandering because it is anti-democratic. It offends our sense of fairness when state legislators fix voting rules to their party’s advantage. In Texas, 58% of voters voted GOP in the 2024 elections for the U.S. House of Representatives. But thanks to the way the GOP state legislature drew the district lines for those U.S. House seats, the GOP candidates won two-thirds (66%) of the state’s seats. Texas is not alone; the list of badly gerrymandered states includes red and blue states alike, according to the Princeton Gerrymandering Project.

And even though district lines are traditionally drawn every 10 years, most recently after the 2020 census, the Texas legislature is proposing to redraw the lines again so as to increase GOP representation to an expected 78% of seats. In response, the legislature’s Democrats have fled the state to deny the legislature the quorum it needs to make decisions. Now, other states have joined the gerrymandering battle, provoking a kind of gerrymandering arms race.

It didn’t have to be this way.

In 2018 the Supreme Court hinted in Gill v. Whitford that extreme gerrymandering cases might violate the Constitution. But when it faced this question squarely one year later in Rucho v. Common Cause, it held that claims of extreme partisan gerrymandering present political questions that the courts cannot adjudicate. One of the amicus briefs in the Rucho case came from political scientists who have shown mathematically that many gerrymanders now allow the party receiving fewer votes to win the majority of seats reliably and durably. But the Rucho court was unswayed by that fact, and dashed any hope that courts will limit gerrymandering.

Rucho foreshadowed the Roberts Court’s submissive friendliness to the GOP agenda,[i] and has unleashed a predictable race among politicians to please their most bitter and extreme partisan voters – the ones who vote in primaries and control most politicians’ futures – by rigging voting rules in ways that enshrine single party rule, even in instances when most voters choose the other party.

Is there a way out of this mess? Ideas like nonpartisan redistricting systems or switching from single-member districts to proportional representation would indeed solve the gerrymandering problem. But they require the cooperation of the very politicians doing the gerrymandering, which seems unlikely.

As always, the problem must be solved by voters. Unless and until voters vote en masse for politicians who champion real solutions, rule of law and our other democratic norms will continue to crumble. Gerrymandering increases the number of voters required to effect change in this way. But there is no (peaceful) alternative. The best thing we can do is to help our fellow voters to see this.

That means helping to extricate them from the modern media environment, which tends to show voters only the “news” that reinforces their existing partisan and ideological preferences. It frames every new development in ways designed to strengthen attachment to one party.

For example, the Trump Administration’s recent claims that violent crime is on the rise in Washington, DC are demonstrably false. But on right-leaning media outlets those claims are consistently presented as true. Indeed, almost every incident of violent crime in a Democrat-run city is weaponized online to support that same narrative.

After the tragic shooting at a Target store in my home town recently, tweets like this flooded Twitter/X:

Other social media posters suggested that a (federal or state) takeover of Austin’s police department is in order. In fact, Austin’s violent crime rate is 74th among major cities, and has been declining.

This sort of misinformation is of course ubiquitous, and it contaminates our politics by hiding too much truth from too many people, and by inviting us all to create our own truths. Indeed, the Internet is perfectly designed to mislead and anger us.

Elbridge Gerry, from whom the term “gerrymandering” derives, was James Madison’s vice president and member of the constitutional convention of 1787.[i] He was an ardent anti-demagogue, and feared populism and parties. It is ironic, then, that his name is associated with a tool of sharp-elbowed partisanship.

Given the Roberts Court’s acquiescence in these attacks on fair political competition, only voters can disrupt the gerrymandering wars, one person at a time, by engaging our friends, relatives, neighbors and co-workers on the importance of restoring democratic values. We do that helping them understand that their vote is what matters.

When enough of us vote in ways that punish the state legislators who gerrymander — and reward politicians for upholding rule of law, truth-seeking, fairness and respect for pluralism — only then can we expect things to change for the better. — David Spence

[i] The Court has, in Donald Trump’s words, “kept me out of jail.” It has refused to stop the Trump Administration’s unilateral destruction of large swaths of statutorily-created regulations and regulatory institutions. And its timidity in the face of the Administration’s summary deportation of legal residents has sent a signal to Trump, emboldening more power grabs.

[i] Gerry was one of three members who didn’t sign the Constitution, however, because he thought the design unfairly advantaged large and southern states.