The most recent version of the World Values Survey (WVS) came out a little more than a year ago. The Economist had a particularly lucid and useful explanation of its conclusions, including some excellent graphics to illustrate their points.

The survey is the creation of the late comparative politics scholar, Ronald Inglehart, and has been conducted every five years since 1998.

Thirty-plus years ago as a political science graduate student, I read Inglehart’s book Culture Shift. Though I was primarily focused on American politics in my graduate program, PhD students at Duke were required to take qualifying exams in other fields as well. I chose comparative politics (and was lucky enough to be able to study that topic with two terrific comparative politics scholars — Robert Bates and Herbert Kitschelt).

Inglehart’s theory was that in our modern, post-subsistence world we would see cultural values steadily harmonize across nations. A worldwide “post-materialist” value consensus would eventually form. That idea seemed persuasive at the time. We also read Samuel Huntington‘s Clash of Civilizations, but as a sort of significant-but-passe approach of mostly historical importance.

But of course, our optimism was misplaced.

Today, the rise of right populist authoritarianism in Europe and the United States has rekindled interest in Huntington’s argument. And the most recent WVS data suggests that culturally divergent values are sticky, even as societies lift people out of poverty. The world is not yet converging around post-materialist values, at least not yet.

The survey locates national cultural values along two dimensions: a y-axis of religiosity that puts the most secular nations at the top and the most traditional at the bottom, and an x-axis of individualism that places collectivism on the left and individualism on the right. As described by The Economist:

If you look back at the map of 1998 you will see countries scattered across all four quadrants. In the map of 2022, by contrast, most are in just two. … Most countries are now aligned along a diagonal that starts in the bottom left, with strong traditional and collective values, and rises toward the top right, with more secular values and individualism. …

If poorer countries were indeed converging with rich ones in terms of values, you would expect that they would be the ones where values are changing fastest … In fact the survey finds the opposite. Countries that are already the most secular and individualistic are changing fastest and becoming even more secular; those that are most traditional and clannish are changing less and sometimes becoming more traditional, not less. …

The WVS implies that secular and liberal values are no more universal than religious and authoritarian ones. … [B]oth are ways in which people adapt to their circumstances, whether secure or insecure.

In international relations and comparative politics culture matters. China and Russia, or example, fall toward the collectivist/traditional parts of the two-dimensional map; the U.S. and Europe at the opposite end of the diagonal. Samuel Huntington’s culture war thesis seems to have been vindicated, at least partly.

While the WVS characterizes the U.S. as more secular and individualist, that larger cultural divide is obviously present in U.S. politics. A sort of religious/cultural affinity may also explain the appeal of Russia and Putin to MAGA conservatives, assisted by the power and sophistication of Russian propaganda (see here and here).

Democrats and a minority of Republicans struggle to understand why so many of their fellow citizens would vote for a candidate who openly professes admiration for authoritarian regimes, who has lived a life so full of lying, bullying, law-breaking, misogyny, and bigotry, and whose prior presidential term was so inept that virtually all of his closest advisors oppose his re-election. But some voters disregard all that in the hope of getting the policies they want. And for others, fear and resentment of cultural change are powerful emotions that override logic and generate a herd mentality. Those emotions push otherwise good people to pull the lever for Trump and other MAGA candidates who seem to wear their anger and alienation from “elites” like badges of honor.

You may believe that their fears — of losing out economically, socially and culturally — as so unreasonable that they must be a pretext for some ethically inexcusable impulse. And maybe their votes are ethically inexcusable given the risks Trump poses to our democracy and fellow citizens. But these voters feel threatened, and they vote. As described in chapter 4 of Climate of Contempt, the internet amplifies and sustains their fear and resentment in historically unprecedented ways. It is the strongest, most effective propaganda tool in human history.

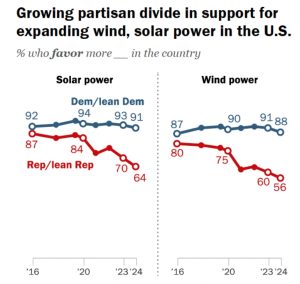

In my book I note how GOP narratives lump climate policy in with culture war issues, which may be why “Republican support for renewable energy and climate policy may be starting to wane.” (p. 122) A Pew Research survey published 5 months after my book went to press offers further support for that proposition.

This may be an artifact of negative partisanship: i.e., rather than choosing a political party based upon its issue positions, voters now choose issue positions based upon their opposition to the “other” political party.

All of this is deeply disappointing, even alienating, to those of us who remember a functioning two party system. It feeds voter alienation and broad-brush revisionist histories that paint the GOP and conservatism as nothing but a tool of economic elites working against the public interest. But bitter partisan tribalism is now a political reality across the political spectrum, even if it is stronger on the right than the left.

Given the speed and proficiency with which right wing media exploits extremism on the left, and the way emotional urgency distorts our perceptions of reality, it would behoove the climate coalition to think more strategically about how those forces affect voters on both sides of the partisan aisle. If we want to forge a congressional majority in favor of a clean energy transition, that sort of deeper understanding will be the first step. – David Spence