U.S. electric customers are facing sharp rate increases, and they are not happy about it. Climate change is part of the problem, but most of it boils down to market forces: too much projected demand for the projected supply. Those supply and demand projections, in turn, is generating some interesting reactions from politicians who are worried about their next election, and from policy types who are reconsidering the ways we regulate electricity markets.

The Problem

Before we get to that, a few basics about the polyglot that is the U.S. electricity market.

- There is a lot of local variation in the structure of U.S. electricity markets. Wholesale markets are regionally-managed by private entities that are overseen by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission; retail markets are managed by state public utility commissions. In some places prices are set by regulators; in others, the price is determined by market forces.

- There is a lot of local variation in the fuel mix of U.S. electricity markets. Generally speaking, blue states have tried to encourage a cleaner generation mix, requiring power providers to source power from renewable sources or imposing greenhouse gas emissions limits on generators. Red states less so.

- Most utilities and other electricity market participants are privately-owned, but about a fourth of them are not. The latter group includes municipal utilities and other state or federal power agencies, as well as rural electric cooperatives.

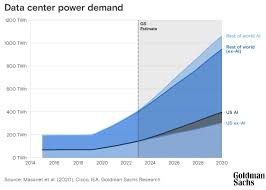

In all of these different market settings, rates are going up. In some places, climate change is creating new risks like more frequent and intense wildfires that raise system costs. In California, for example, PG&E wildfire liability expenditures are a major driver of rate increases (see here and here). But the biggest driver of rate increases nationwide is increased demand for power. Indeed, demand is projected to increase at rates not seen in three-quarters of a century. The sources of that demand growth are electricity-hungry data centers, electrification of transportation and other industries, bitcoin mining, and more.

Plenty of investors are willing to invest in new supply to match that demand, and are ready to build hundreds of new power plants across the country. Unfortunately, grid managers and regulators have been slow to grant those plants the approvals they need to begin construction. In many places regulators seem overwhelmed by the number of applications; in other places the lack of transmission capacity has slowed the approval process. And the threat of NIMBY opposition — to power plants and new transmission alike — acts as drag on the entry of new supply into the market.

The vast majority of the plants waiting for the regulatory OK are solar farms and battery storage facilities; wind farms and natural gas plants constitute most of the remainder. Investor preferences for clean energy reflect the economic advantages of renewable power, and the unmet demand for electricity storage in many parts of the grid. Renewable power is cheap, and renewable energy power plants and battery plants can also be build more quickly than natural gas generation.

Politicians want Solutions

This situation has politicians running scared. A sample:

- In places where rates were already high — mainly the northeast and California — politicians are looking for ways to dampen those rate increases.

- In Connecticut and New Jersey, lawmakers and regulators are using taxpayer money to subsidize reduced rates. And the Democratic nominee to be the next governor of New Jersey has pledged to freeze utility bills for one year.

- In Pennsylvania, Governor Josh Shapiro filed a legal complaint with the FERC, challenging rate increases in the wholesale market that will be passed on to Pennsylvania ratepayers.

- Hoping to bring prices down by increasing supply, Maryland lawmakers recently passed laws to build more power plants in their state, and to streamline regulatory siting approvals for renewable power plants.

- The governors of Indiana, New York and California have complained about the rate increases, and the California legislature is considering emulating New Jersey and Connecticut by subsidizing electric bills. [Severin Bornstein has provided a terrific explainer into the bill changes coming in California.]

- Elsewhere, some people are talking about rolling back parts of the move to competitive electricity markets: e.g., (i) re-regulating electricity prices in places where market pricing exists today (see here and here), or (ii) letting investor-owned utilities get back into the business of owning power plants in competitive markets.

Some of these policies will shift costs from ratepayers to government (read: taxpayers). For politicians, this is attractive because the benefits of subsidies are much more apparent to voters than their costs: i.e., voters can see how subsidies reduce their electricity bills, but tend to be oblivious to how they increase their tax bills (or the budget deficit). And in states where the tax regime is progressive, subsidies shifts costs from poor to rich. Indeed, this was the theory behind the Inflation Reduction Act, which drastically lowered the cost of building new energy transition infrastructure: not just wind and solar farms, but clean energy manufacturing, carbon sequestration projects, electric vehicles, hydrogen production and more.

Is Public Ownership the Answer?

Regardless, private capital must be mustered to cover the costs of providing a reliable electricity supply one way or the other, whether directly from private investment in energy infrastructure or indirectly from taxpayers. All of which has some academics and pundits wondering whether it makes more sense to encourage public ownership of electric power provision.

UCLA’s William Boyd, Penn’s Shelley Welton, and others have made the case that free markets permit sellers of electricity to capture rents at the expense of buyers. They suggest that public provision of electricity can guard against that effect,[1] and better organize investment in the energy transition. Democrats mostly agree that the market is failing to build the transmission we need or to approve the renewable plants investors want to build. But as the 2026 election season heats up (pun intended), Democrats will squabble among themselves about whether government ought to steer investment in those directions via regulatory change, or instead to build the needed infrastructure itself.

And of course, public ownership is not a pancea.

First, as a class, government-owned utilities do not have a better track record on environmental performance measures than investor-owned utilities. For every Austin Energy (good performer) there is a TVA (bad performer). Second, government owned utilities will reflect the priorities of their political overseers. Given the GOP’s recent turn against clean energy, government-owned utilities can lead the energy transition only when and where Democrats are in charge.[2] Indeed, IOUs in blue states (as a group) have not exactly resisted the energy transition; some, like PG&E, embraced renewable energy with gusto.

Third and finally, as climate change makes the reliable provision of electric service more difficult and costly, one wonders whether governments will be willing to take over investor-owned utilities’ generation and transmission assets and the liability risk that comes with them. Governments (taxpayers) would have to pay for those assets. And when massive wildfire liabilities forced PG&E into bankruptcy, neither the state nor its municipalities were interested in buying out the PG&E system. That left regulators facing a conundrum: how to protect ratepayers from rate increases while keeping PG&E solvent. A federal court ordered the company not to pay dividends to shareholders until it had complied with tree trimming and other safety rules relating to wildfire risk. Katherine Blunt’s execellent book, California Burning, picks up the story from there:

On one level, [the judge’s] solution made sense. If the company couldn’t fulfill its basic safety commitments, why should investors benefit? But in attempting to address one set of risks, the proposal introduced another. PG&E’s financial health after bankruptcy would depend on its ability to make regular dividend payments, a significant factor in attracting more patient investors that . . . would stick around long enough for the company to have a chance to stabilize. . . . Even if the company fell out of compliance on tree work, dividends would help it raise money to make other safety investments.”[3]

On the one hand, public ownership of PG&E would eliminate the need to pay dividends, and to attract capital directly from capital markets. But the capital would still be needed, and it would have to come from taxpayers. In that event, state politicians would have to take responsibility for the way in which the publicly-owned utility manages such a complicated set of responsibilities and risks. If a government utility were to make the kinds of mistakes that PG&E did, the resulting public anger would be directed at state politicians rather than PG&E.

As U.S. ratepayers face a future of increasing rates, politicians will have to grapple with this question of how to share the cost of ensuring reliable service between ratepayers and taxpayers in an increasing-cost environment. It will be interesting to see how different states make that choice. Their decisions will have significant political implications, as they already have in the New Jersey governor’s race. And they may shake up the way we regulate electricity markets in new and different ways. — David Spence

—————–

[1] But see a rejoinder to this argument from Harvard’s Edward Glasser.

[2] Though perhaps Democrat-run cities within red states may be able push the energy transition, assuming state legislatures do not intervene to stop them.

[3] Blunt, California Burning, p. 210.