One of the few low-carbon energy technologies that the Trump administration is not actively trying to hobble is nuclear power. (Geothermal energy is another.) Nuclear power boosters have been heartened recently by the tech industry’s interest in 24/7 clean power to power its data centers, as well as recent state government interest in developing new nuclear power plants. If their efforts can bring the cost of nuclear power down it will be a boon to the energy transition in these tough political times.

The recent announcement by Governor Kathy Hochul that New York State is committing itself to building new nuclear power plants is one of a the series of recent developments signifying the rehabilitation of nuclear power in the eyes of Democrats and the ideological left. Twelve states still restrict construction of new nuclear power plants — all about one of them solidly controlled by the Democratic Party. But a decade ago that number was much larger. And New York aside, most of the recent pro-nuclear rumblings come from red states like Texas, Tennessee and South Carolina. (Compare the UK, where the left-leaning Labour government is the more aggressive proponent of new nuclear power plants.)

Is a note of caution in order?

Despite all this, those of us who have been around energy policy for a long time will be hesitant to predict a “Renaissance“ for nuclear power just yet — if only because we have seen so many similar predictions turn out to be wrong.

Since the accidents at Three Mile Island (1979) and Chernobyl (1986) there have been periodic attempts to kickstart new project development — most notably, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission’s (NRC) 1989 streamlining revisions to its licensing process, and the generous financial incentives for new nuclear projects contained in the 2005 Energy Policy Act. But in the 21st century only three new commercial reactors have been added to the American nuclear fleet. And after nearly a decade of optimism about next-generation small modular reactors (SMRs), SMR projects have not fared well in the marketplace.

The 2005 congressional incentives stimulated many new project license applications, but ultimately resulted in only two new reactors, Vogtle Units 3 & 4, completed just this year in Georgia. Those two plants depended on additional financial help from the state of Georgia to make it across the finish line, and came in at more than twice their originally budgeted cost. A third new plant, Watts Bar Unit 2 in Tennessee, came online in 2016; its construction was begun way back in 1972, but was delayed between 1986 and 2007. But most of the plans for new nuclear power plants stimulated by the 2005 legislation were all abandoned after the Fukushima accident in 2011.

The primary stumbling blocks for new nuclear projects have been both financial and political. By most measures of cost, nuclear power has difficulty competing on price with renewables or natural gas fired power. The rejoinders offered by proponents of next generation nuclear power are that: (i) tech-to-tech, per-kwh cost comparisons omit nuclear’s weather-dependency advantages over renewables, and its emissions advantages over natural gas; and (ii) new, smaller modular reactors built in the factory ought to achieve economies of scale that bring down costs.

However, it is not certain that cost parity would stimulate investment in new commercial nuclear plants. In parts of the country with competitive wholesale power markets (about 60% of the market), investors in new power plants are not guaranteed positive net returns on their investment. For these prospective investors, the high up-front capital costs and future market uncertainty make nuclear power seem too risky. The Vogtle and Watts Bar plants were built under institutional arrangements that insulated investors from market risk and guaranteed a positive return on investment.

Still, nuclear power is a reliable, low carbon source of electricity, which is why the tech sector likes it. A Texas consortium led by former governor Rick Perry hopes to lure data centers to the Lone Star State by providing the kind of financial security that will enable new plants to be built. In South Carolina, policy makers are reconsidering their 2017 abandonment of two partly-constructed reactors for the very same reasons. Meanwhile, in Tennessee and New York, it is government-owned developers who are planning to invest in new nuclear, making an end run around the private market. And an internet search for “small modular reactors and data centers” will reveal many more stories chronicling tech sector plans to build new small modular reactors to support new data centers.

What could slow all this momentum? Local political opposition to nuclear power. Nuclear power optimists sometimes under-estimate how fierce, formidable and longstanding that opposition can be.

The politics of nuclear power

Anti-nuclear activism was a staple of the environmental movement in the 1970s. And the aforementioned accidents at TMI, Chernobyl, and Fukushima seemed to vindicate fears that the technology is unsafe, embedding the Simpsons’ portrayal of the nuclear industry into popular culture.[1] Many people still hold that view, or will come to embrace it when someone proposes building a nuclear reactor or nuclear waste disposal facility near them.

Consider the saga of the 1980 Low-Level Radioactive Waste Policy Act (LLRWPA), which obligated states to make a choice: either establish an in-state disposal site for in-state waste, or enter into a compact with other states to build a common disposal site for those states’ low-level radioactive waste. In the end, many states chose neither.

State compacts proved unstable because the states selected to host the disposal site simply exited their compacts. States that tried to site their own disposal facilities found that local opposition was so intense that the public officials involved in site selection had to travel incognito and drive rented cars to avoid threats and vandalism directed at them. Ultimately New York State refused to select a site and sued to have the law overturned.

Or consider the 1982 Nuclear Waste Policy Act, which required the Dept. of Energy to develop a federal repository for high-level radioactive waste. Members of Congress came under intense pressure from constituents worried that their state might be selected to host the repository. So in 1987 Congress mandated creation of the Yucca Mountain site in Nevada — over the objection of Nevada Republicans and Democrats alike. But Nevadans were persistent in their opposition and in 2008 extracted a promise from then-candidate Barack Obama to stop the development process. He made good on that promise after it helped him win a close primary election in Nevada in 2008.

NIMBY opposition to nuclear energy or nuclear waste is fierce.

Tempered Optimism

On the other hand, it feels like the politics of nuclear power is changing, particularly as climate-related harms become more and more expensive. And as people begin to look more closely at nuclear power, they find the industry harder to demonize. Here’s what I said about nuclear power in the Introduction to my book:

The spark of interest that led to my own forty-year career in energy law began that way. When I was twenty years old, the Three Mile Island nuclear power plant melted down about thirty miles from where I was living. That experience triggered my subsequent support for anti-nuclear-power activism. At the time, I was persuaded by messaging that the nuclear industry was dangerous and deeply corrupt, even evil. There was a social and cultural element to the way I formed those beliefs, one that involved not only my friends and fellow inhabitants of the political left of center (where I still reside on most issues) but also pop-cultural influences. But as I studied and worked on power-sector issues, I began to see that I had been tarring the industry with too broad a brush. The moral clarity I felt about nuclear power and electric utilities became muddied by a more complicated reality, and my views of these industries and their people moderated significantly.[2]

A similar evolution may be softening left-wing opposition to nuclear power today. This year Oregon came close to lifting its ban on new nuclear construction, and many climate hawks have come to see it as a part of the mix of clean firm power necessary to back up renewable energy.

So while we ought not to turn a blind eye to the obstacles, tempered optimism about the next Nuclear Renaissance may be justified. Perhaps the strongest basis for optimism lies with its tech sector enthusiasts, who are swimming in so much cash that they may be willing to pay above market rates for the clean, firm power that nuclear reactors offer. For now they seem willing to seed enough new investment to realize some of the economies of scale in production that nuclear boosters have promised.

But the final step will be securing enough public acceptance to get individual new nuclear reactor projects across the finish line. That will require champions other than project sponsors. It will also require the kind of dialogue and active listening that I discuss in chapter 6 of my book. And for many reasons, that mind set seems to be in ever-shorter supply in the Internet age. Still, if the Trump era incubates and weans the next generation of nuclear reactors in the ways described above, that will help the energy transition in the long run. — David Spence

————

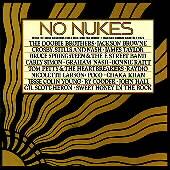

[1] For readers not familiar with the cultural context of antinuclear activism in the late 20th c., it is worth noting that the Three Mile Island accident occurred less than two weeks after release of the blockbuster Hollywood film The China Syndrome (with Jane Fonda, Jack Lemmon, Michael Douglas), in which owners and operators of a nuclear power plant try to cover up an accident at the plant. Shortly after the real-life accident, many of the popular musicians of the day (Bruce Springsteen, Bonnie Raitt, James Taylor, Jackson Browne, Carly Simon, and Crosby, Stills, and Nash, among others) staged a series of anti-nuclear concerts in New York City under the banner of an organization called Musicians United for Safe Energy (MUSE). That effort yielded the polemical concert film No Nukes, most of which can be found on YouTube. Another film about the nuclear industry, Silkwood (with Meryl Streep, Cher), posited that the automobile crash that killed a real-life industry whistleblower was an intentional homicide orchestrated by industry officials to prevent her from disclosing the existence of dangerous corner cutting in the construction of a nuclear power plant.

[2] David B. Spence, Climate of Contempt, p. 4.