One feature of the modern information environment is that it allows conspiracies and utopian fantasies of the left and right to grow undisturbed by reality. Utopian ideas are often the product of the irresistible notion that “if everyone thought like me, everything would work well.” Fictional movie villains often take this impulse to destructive ends. Marvel comic bad guy Thanos professed good intentions when he justified eliminating half the world’s population to save natural resources from depletion.

Lately, bad utopian ideas seem to be particularly attractive to left-brained tech entrepreneurs who have achieved enormous financial success in the business world, and/or to those predisposed to believe that most collective problems have one logical “right” answer.

People who achieve great success in the competitive market through ingenuity, creativity, and dogged (messianic?) persistence learn to trust their own instincts. But their instincts can be a dangerous when applied to domains beyond their business expertise. So it is with the latest “Emperor‘s new clothes“ utopian fantasy: The Network State.

The proponents of The Network State imagine a world in which pesky pluralism is not a problem because all the members of society are “aligned.” In their words:

A network state is a social network with a moral innovation, a sense of national consciousness, a recognized founder, a capacity for collective action, an in-person level of civility, an integrated cryptocurrency, a consensual government limited by a social smart contract, an archipelago of crowdfunded physical territories, a virtual capital, and an on-chain census that proves a large enough population, income, and real-estate footprint to attain a measure of diplomatic recognition.

At its end state this a world in which members can be left alone without having to accommodate their activities to the interests of others. It is (for very similar reasons) every bit as illusory the dictatorship of the proletariat described by Karl Marx in The Communist Manifesto. (Both are harmonious societies without the need for a government – democratic or otherwise.) The fuller description of the Network State is replete with futuristic jargon worthy of L. Ron Hubbard, including “multisig,” “1-network,” and “Triforce.” Like Marx, it envisions a trajectory of change that starts modestly and lurches into absurdity at its end.

But because this idea has the partial or full support of the tech billionaires closest to Donald Trump and J.D. Vance, we have to pay attention to it (unfortunately).

The Network State seems to be a stepchild of the cryptocurrency movement of the 2010s, some of whose adherents are involved in this new venture. Recall that crypto was touted as a better, more secure replacement for government-backed legal tender (a/k/a “fiat currencies”). But it turned out to be a mere commodity of wildly fluctuating value, though it is sometimes used as a medium of exchange by its devotees. Crypto’s lack of stability hasn’t dampened enthusiasm for it among those who long for a stateless collective. But the notion that the messy byproducts of pluralistic conflict can be banished from society or governance is a fool’s errand.

In Climate of Contempt, I write the following:

Too many voters seem to be losing site of the symbiotic relationship between government and markets. On the one hand, markets depend on government to function and thrive. Fewer laws do not mean more economic freedom. To the contrary, the creation of economic value requires law and regulation. Aspiring entrepreneurs in dangerous lawless regions do not enjoy meaningful economic freedom; nor do small businesses that are smothered in the cradle by underregulated monopolies or oligopolies. …

On the other hand, the law creates only the conditions for value creation; it does not create that value. Countless decisions made by economic actors – to invest, to create and innovate, to persist in the face of challenges, and to engage in exchanges – are the source of that value. This connection, too, ought to be self-evident. (pp. 11-12)

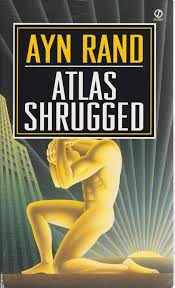

The Network State embraces the second truth so tightly that it ignores the first. In so doing it stands in a long line of utopian libertarian ideas throughout American history. It seems to be particularly close relative of Ayn Rand’s Galt’s Gulch. Rand’s utopian fantasy was first published in 1957, during the “International Geophysical Year” (IGY). IGY was a meeting of physical scientists that produced optimistic predictions about how technology would improve the lives of us all. Three decades later musician Donald Fagen mocked those predictions in a song called “I.G.Y..” That song also seems to have foreshadowed some aspects of the Network State: “A just machine to make big decisions / Programmed fellas with compassion and vision.”

The Tea Party movement of the early 2000s also posited that government was the enemy of freedom. It too was satirized mercilessly in an episode of the Fox animated series Family Guy, in which the hapless family patriarch leads a tea party movement to dissolve his town’s government. Predictably, anarchy ensues and people are unhappy. So the protaganist calls a meeting of the townspeople:

Now that we’ve freed ourselves from the terrible shackles of government, it’s time to replace it with something better. The first thing we need is a system of rules that everyone must live by. And since we can’t spend all our time making rules, I think that we should elect some people to represent us, and they should make rules and choices on our behalf.

Now this may be kind of expensive, so I have a plan. Everyone should have to give some money from their salary each year. Poor people will give a little bit of money and rich people will give a larger amount of money, and our representatives will use all that money to hire some people who will then provide us with social order and basic services. Some of our representatives may end up being bastards. But you know what, that’s OK because later we are going to have more elections and we can use those elections to get rid of the bad guys and replace them with good guys, and then the system will just keep going on and on just like that.

So who’s with me? Will you join me in trying this new crazy thing? Then let’s do it.

Yeah, and we did it all without government.

Liberal democracy is a system of collective governance that accepts the reality of pluralism. It aims to reconcile freedom with pluralism. Utopian plans that rule out pluralism or tame it by way of an imagined benevolent dictator are fantasies.

The Network State is not a democracy:

Can that founder break up the Triforce, splitting their authority into some kind of multisig? Sure, just like the founder of a startup company can choose to give up board seats. But it’s easy to give away power and hard to consolidate it, and you need that power sometimes to make hard but important non-consensus decisions. That’s why dual-class stock to maintain control is used by both the US establishment and their opponents.

Trump whisperer Peter Thiel has famously said that he is done with democracy. He has also funded efforts to create societies on ships or islands in international waters, beyond the reach of any national government – so-called “seasteading.” This is Galt’s Gulch redux. Unsurprisingly Thiel is one of tech billionaires who support The Network State. And Donald Trump has embraced the idea of “Freedom Cities,” an idea that sounds suspiciously like the sort of state-within-a-state ideas found on The Network State web site.

Thiel is representative of an increasing number of voters who seem unwilling to accept democratically-produced policy outcomes that they don’t like. This would seem childish and silly if it wasn’t such a strong indicator of the declining legitimacy of American liberal democracy. The internet allows meritless ideas like these to seem profound, by shielding their adherents from information and people that would challenge them. It walls off the marketplace of ideas from competition, allowing deficient ideas to thrive in the same way that trade barriers protect inefficient firms.

We live in a big pluralistic society. That is a pesky fact of life. No acceptable system of collective governance can avoid that. In the reality-based world, democracy does a better job of accepting that fact of life than any other form of government. — David Spence