To my mind, some members of the climate coalition spend too much time and energy fighting with one another about which carbon-reducing technologies to support or oppose. Particularly in these politically problematic times, we ought to be humbly agnostic about those questions. Why not celebrate every technological advance that makes lower-carbon energy better, cheaper or easier? But we don’t. Pro-energy transition populations online regularly denigrate particular energy transition technologies that they don’t like. I have never really understood that.

For example, many good people — researchers, investors, and companies — are working to help make carbon sequestration better and more affordable. I have posted before (see here) about the disdain with which (mostly progressives) treat “carbon management” efforts, and maybe carbon sequestration will turn out to be too expensive or ineffective. But they cannot possibly know that now. Which makes me wonder about the thought process that produces their certainty.

Within the last month or two my professional news feed has included the following stories:

- a LinkedIn post by my University of Texas colleague Ben Leibowicz describing (with justifiable pride) the work of his students and faculty colleagues in this field

- a Politico story about new investments by ExxonMobil in carbon management and sequestration

- an unsolicited email from a young African lawyer whose work aims to further the energy transition by focusing on carbon management in his country, and who wants to collaborate,

- the City of Palo Alto’s recent deal with Occidental to sequester carbon, adding momentum to that company’s carbon sequestration projects one of which is scheduled to come on line later this year, and

- another Politico story about how Louisiana legislators are torn over whether to support development of carbon sequestration projects because it might look like they are acknowledging that climate change is a real problem

As the GOP turns against the energy transition, internecine disagreements within the climate coalition about technologies seem even more frustratingly counterproductive, irrespective of their sincerity.

The quotation in the headline of this post is one I use in Climate of Contempt. It is often misattributed to Yogi Berra (or Niels Bohr), and it captures why we ought to be more humble about predicting the techno-economic future. Yet the public debate is rife with selective optimism about how reliable, economical and scalable (dis)favored technologies will be in the future. If we want a future powered only by wind, water and solar energy, then we can easily start to view that future through rose-colored glasses, and alternative paths as wrongheaded. If we want a nuclear powered or gas+CCS powered or geothermal powered future, then we can easily become optimistic about the future costs and technological capabilities of those technologies as compared to alternatives.

Crucially, energy experts don’t have a great track record predicting which technologies will be cheapest or “best” in the future. Odds are that one or more will get a lot cheaper and better, but we don’t know which one(s). Consider this history:

- More than 70 years after experts declared that nuclear power would soon be “too cheap to meter,” we are still waiting for that prediction to come true.

- In my lifetime predictions about nuclear fusion energy have been like the joke my Brazilian friends make about their country: “Brazil is the country of the future and always will be.”

- The first edition of the energy law text of which I am co-author described shale oil and gas as an energy source of the distant future, a resource locked away in rock that would be far too expensive to exploit during our lifetimes.

- Similarly, the decline in the cost of photovoltaic solar panels over the last two decades was much more rapid than even the most optimistic among us predicted.

Sometimes energy pundits point to specific predictions that came true shortly after they made them. But usually those pundits are sampling on the dependent variable. There were frackers and solar developers who predicted the breakthroughs that benefited those technologies in the 21st century, but they did so annually for many years until those breakthroughs happened. The fact that the last of those predictions came true shortly thereafter did not make those people prescient.

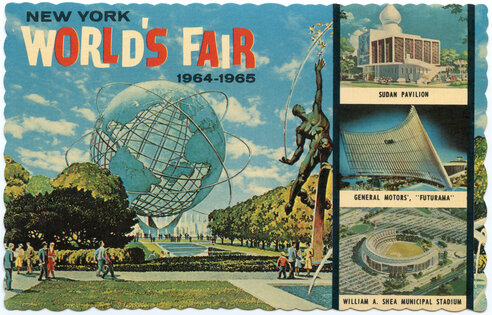

Ten years ago an auto industry analyst assured me that driverless cars would have replaced taxi drivers by now. Fifty-plus years before that, while attending the New York World’s Fair as a kid, we were told that the AT&T “picture phones” on display would become the norm in 5-10 years. And 50 years before that World’s Fair, Thomas Edison apparently expressed optimism about the imminent commercial exploitation of the wind and the sun for inexpensive power. These predictions are all coming true in one form or another, but far later than their boosters predicted.

Punctuated technological change is a feature of energy markets, but an unpredictable one. I tell my students to read specific predictions about the energy future with a very critical eye.

The good news is that the purveyors of all energy technologies are engaged in a constant effort to make them better and cheaper. So are researchers in universities and think tanks. Every week there are papers presented at energy transition conferences diving into the technical and economic minutae of how this or that technology might (or might not) have a role in a net zero future. The people that present those papers are trying to solve an important problem, even if they disagree on how to do that. They will lobby us to think more positively about their preferred technology than others; that’s human nature. So we need to be discerning consumers of energy technology news.

My book tries to explain how and why we can achieve that discernment by being curious, not judgmental. Most of the commercializable clean energy breakthroughs of the future will be the product of somebody’s desire to do good, ambition to make money, and/or to burnish their reputation. Those innovations will come when they come. And when they do, the news will surely be run through the meat grinder of online lobbying and partisan policy competition. “That sounds like [INSERT INDUSTRY] propaganda!”

Don’t be part of the meat grinder. Instead, tip your hat to all the researchers who work to solve these kinds of energy transition problems. They are doing the real work that will create progress. – David Spence