It is no secret that the fragmentation of our media environment along ideological lines is undermining scientific literacy and belief and scientific truths. We have seen this in climate and energy policy for decades. But today it is even more pronounced in public health policy around the issue of vaccines and virology.

How vaccine skepticism grew

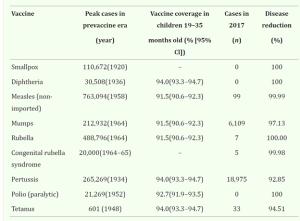

It is difficult to overstate the positive effects of vaccines in human history, as the chart below shows. (Click here to enlarge; click here for the source document.) So the rapid growth of vaccine skepticism in the United States is troubling.

Belief in falsehoods about vaccines predates the appointment of a leading source of vaccine disinformation as Secretary of Health and Human Services; indeed, it predates the pandemic. (See here and here.) But it has accelerated in the era of social media, podcasts, and the resulting “democratization” of expertise. Within the last few months I had separate encounters with two good people that I know that brought home just how powerfully online propaganda can spread distrust of public health programs like vaccines.

One encounter was a friend’s online reaction to a Facebook video by a doctor correcting misinformation about vaccines that was spread by Senator Rand Paul. Paul, a long time vaccine skeptic, said in a congressional hearing that “no healthy child” had died from COVID-19. The correction video simply cited empirical data and studies demonstrating that Sen. Paul’s claim was false. My friend’s reaction to the video was a heated one (“you fucking leftists”), and raised other anti-vaccine claims, including that the COVID-19 vaccine causes (myocarditis-related) heart failure, and that some people who were forced to take the vaccine died as a result.

For reasons I don’t want to get into here, I didn’t respond to my friend online. But I did go looking for peer reviewed scientific studies addressing his claims. I found several studies in various scientific and medical journals, as well as webpages summarizing the research on the myocarditis claim from The British Heart Foundation, the US National Institutes of Health (NIH), and the Centers for Disease Control (CDC). They all say basically the same thing, which is that the incidence of myocarditis following receipt of certain COVID-19 vaccines DID increase, particularly in young men, but that the risk was very low, and lower than the risk of developing myocarditis from contracting COVID-19 itself.

Public health policy is and ought to be based on that kind of data. Multiple peer reviewed ideological studies demonstrate that the widespread administration of the Covid COVID-19 vaccine saved millions of lives and many billions of (perhaps more than a trillion) dollars. But for people who lost a loved one to heart failure after receiving the vaccine, those probabilities don’t matter much. The lockdown meant that some people felt forced to take the vaccine against their will; and when members of that subset experienced serious health consequences after receiving the vaccine, it is easy to see how they and their loved ones might gravitate toward belief in anti-vaccine propaganda.

The other encounter was a conversation with a very smart and accomplished person (with whom I am close) who told me that “Anthony Fauci should be drawn and quartered as far as I’m concerned.” The comment took me by surprise in its vehemence, and because it revealed an understanding of Fauci‘s record of public service on COVID-19 matters that is very different from my own. I was vaguely aware of congressional Republicans expressing the belief that Fauci lied about the origins of the COVID-19 outbreak, and that they blame Fauci for decisions by the first Trump administration and the Biden administration to support lockdowns (masking, social distancing, stay at home orders) and vaccinations as a way of containing the spread of the virus. And I was aware that those views had become common online in certain information ecosystems. But I also thought that it was generally established that these attacks on Fauci were not credible, and that state and local governments had been the source of most lockdown decisions.

So, I once again went looking to see what I could find about these issues. Just as I had recalled, the case against Fauci for allegedly lying about the origin of COVID-19 is a pretty weak one that involves semantic disputes over what constitutes “gain of function research” in epidemiological circles. And despite widespread congressional Republican support for indicting Fauci, no such indictment has been issued — even by the Trump Administration Department of Justice (so far), whose willingness to bring speculative lawsuits is well established.

As to claims about the adverse effects of the lockdown, those cannot be so easily dismissed. One 2021 meta-analysis of 24 studies from Johns Hopkins concluded that the lockdown had only a very tiny impact on mortality, reducing mortality by only 0.2% (in the United States in the European Union) while imposing “enormous economic and social costs.“ The authors later revised that estimate upwards in response to comments, to 3.2%. A later World Health Organization meta-analysis found a much larger beneficial effect, but cautioned that some of the studies it examined lacked methodological rigor, and that measuring these effects is extremely difficult because of the fluid nature of public understanding of the threat, federal state and local government policies, and behavioral reactions to the COVID-19 threat throughout the pandemic.

Of course, even the low estimate (3.2% increase) in averted deaths represents a significant number of people who survived because of lockdown measures. But the social and economic cost of a lockdown were indeed enormous. We won’t be able to measure the harm associated with school closures for a long time.[1] And I have no intuitions about how to measure “saved lives” against those “social, educational costs to children” and “lost economic activity.” But both sides of that brutal cost of benefit analysis seem large to me.

Accepting complexity and extending grace

But in the midst of intense political warfare it is difficult to extend a little grace to one another, to give the other the benefit of the doubt. We need someone to blame for our pain. So supporters of a strong public health response to the pandemic are reluctant to acknowledge the pain of those who suffered from that response; opponents of vaccines and lockdowns are reluctant to acknowledge that public health officials were doing their best to address an unprecedented and complicated deadly threat.

The pandemic was a uniquely powerful and extended driver of mental anguish around the world. It imposed varied and unprecedented costs on people: some from contracting the disease itself, and others from the measures taken to fight the spread of the disease. That it provoked motivated reasoning about science is no surprise. But it is also a prototypical example of the way the ideological and social media amplifies negative emotion, to the advantage of politicians and partisans who want to exploit that emotion.

In chapter 6 of my book I summarize research that suggests the value of trying to (i) recognize that others are winding us up in this way, and (ii) avoid rushes to judgment, particularly on questions of moral blame. When we turn public policy disagreements into morality plays, the temptation to grab onto false or misleading blame narratives is powerful. And when too many of us do that, we provide an equally powerful incentive for politicians to take up those narratives in order to win our votes — creating a destructive feedback loop between politicians and voters. It is a vicious cycle.

Rand Paul’s suggestion that no healthy child died from COVID-19 was an attempt to minimize one side of that risk in order to cast blame on the well-meaning public officials. He protects himself against primary challenges in Kentucky by burnishing his MAGA/MAHA credentials. But the public officials he villifies were people grappling with a complicated scientific question, an unfamiliar and deadly threat. However sincere Sen. Paul is, he is nevertheless misleading the public (and perhaps himself).

He is not alone. In the case of vaccines, podcasters like Joe Rogan have helped people reject the scientific consensus on vaccines and to rely on anecdotal evidence and unfounded theories that pharmaceutical companies have captured the FDA so as to promote ineffective and dangerous vaccines. (See also here.) Rogan has a huge following, particularly of disaffected young men who frequent online communities. If everyone in your online social media group believes something, it is easy to conclude that that’s something is true, particularly if it is reinforced day after day.

That is how we end up with irresponsible leaders of our public health system like Robert F. Kennedy and Dr. Oz. Pockets of online misunderstanding and skepticism harden and grow, and become impenetrable by the real truth. Activist skeptics vote in primary elections, forcing members of congress to cater to their beliefs — or at least not to oppose them.

Climate science experienced something similar in the 1990s and early 2000s, when fossil fuel companies funded groups like the Heartland Institute, which disseminated disinformation about climate science, undermining the efforts of climatologists to spread awareness of climate risk. The encouraging news is that since then, the number of climate deniers has dwindled. Most high profile science deniers have conceded that the climate is warming, and that human activity is driving that change. The discouraging news is that the United States still lacks a strong national climate policy.

But the climate debate is now focused on the question of whether the cost today of reducing carbon emissions quickly is worth the benefits it will bring tomorrow and for decades thereafter. This is a complex question, analogous to whether lockdowns provided a net benefit to society. A large body of scholarly research supports the conclusion that the benefits of reducing carbon emissions now greatly exceed the costs. But more extreme claims of climate harm are more speculative.

We can all do better if we extend a little more grace to one another: to public officials grappling with scientifically complex problems and to our fellow citizens who see things differently than we do. We all tend to want to avoid the inconvenient truths, and neither COVID-19 policy nor climate/energy policy offers only easy, win-win choices. But when we feel urgently about which is the right choice, we tend to turn a blind eye to the difficult consequences of that choice. If we keep doing that, we will keep getting the kinds of leaders and policies we have been getting lately. — David Spence

—————–

[1] Full disclosure: I was president of the Board of Trustees of a Montessori school throughout the lockdown, and had a front row seat to the anguish of parents — first about the risk of their child contracting COVID-19 at school, and later about the lost social and educational development that came from long school closures.