Among energy and environmental policy wonks in the northeast, an obscure provision of a 1972 environmental law is at the heart of a dispute over a natural gas pipeline. The provision in question is Section 401 of the Clean Water Act, and it gives states a veto over federally-approved energy projects in order to protect the quality of state waters. But over time, it has become a tool states wield to further their broader climate and energy policy objectives.

Section 401 is a bit labrynthian. It includes procedural quirks that have triggered fights between states and federal agencies. But its substance is the more interesting part. It requires federal agencies that are considering permit applications for projects that may result in a discharge into navigable waters to secure a certification from the applicable state that the project in question will comply with various water quality protection provisions of the Clean Water Act.[1] (I told you it was labrynthian.)

Section 401 provokes controversy because it gives states a veto over some projects that the state would not otherwise have, even in cases where state regulatory authority is otherwise preempted by the federal licensing statute. Critics charge that some states use this authority in overlay broad or arbitrary ways that are unrelated to water quality.

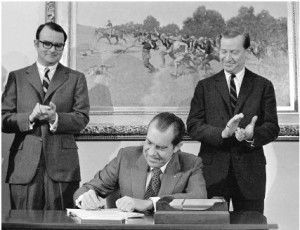

But courts have generally read state authority under this provision broadly. Litigation over the breadth of this state power arose first in the context of hydroelectric projects (much of it in New York State). The Federal Power Act preempts most state licensing power, and in late 20th century there arose multiple cases in which local opposition to new hydro projects led states to either (a) balk at the issuance of 401 certificates, or (b) impose conditions on those certificates that Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) considered to be unrelated to water quality and therefore beyond the state’s authority under section 401. The Supreme Court eventually resolved some of these disputes in PUD No. 1 of Jefferson County v. Washington Department of Ecology, 500 U.S. 700 (1992), authorizing the state to require hydro developers to maintain certain minimum flows in waterways because those water quantity restrictions were related to water quality.[2]

In the 21st century conflict over the breadth of state authority under Section 401 has shifted to the natural gas pipeline licensing, and much of it has been centered in New York State. Public opinion in New York State is sharply opposed to the use of hydraulic fracturing (fracking) to produce natural gas in the New York part of the Marcellus Shale, and the state has banned the practice. Since then the state has also denied 401 certificates to natural gas pipelines that would bring gas from the Pennsylvania part of the Marcellus into New England, New York City, and Long Island, where gas supplies are tight (and prices high) in the winter. After the State pursued the early closure of the Indian Point nuclear power plant, it created a downstate power supply gap that has been filled by natural gas, making gas-based price spikes more painful for electric ratepayers.

The State ties is refusal to issue 401 certifications for natural gas pipelines to its concerns about the impact of fracking on water supply and to climate concerns. This is a popular line of attack with New York voters, where infrastructure associated with “fracked gas” is unpopular.

Critics charge the state with misusing its authority under Section 401 in various ways, including the claim that its opposition is arbitrary because the risks to water quality from the construction and operation of natural gas pipelines are significantly lower than risks associated with other activities that New York permits in or around its waterways.[3]

For its part the Trump Administration sees Section 401 as an impediment to energy infrastructure permitting, and has tried to narrow its scope. Those efforts have so far yielded little. For a closer look at the federal policy flip-flops on these issues from 2016 to now, and the associated litigation over the scope of Section 401, see the Congressional Review Service’s summary here.

All of which is prelude to New York’s ongoing consideration of a 401 certificate for the Northeast Supply Enhancement Line (NSEL), a new natural gas pipeline that would bring gas from Pennsylvania (where fracking to produce natural gas is permitted) into the New York City area by way of New Jersey. New York had previously denied the project a certification, but the project has been resurrected in the wake of negotiations between the State and the Trump Admininstration over an offshore wind farm that New York wants.

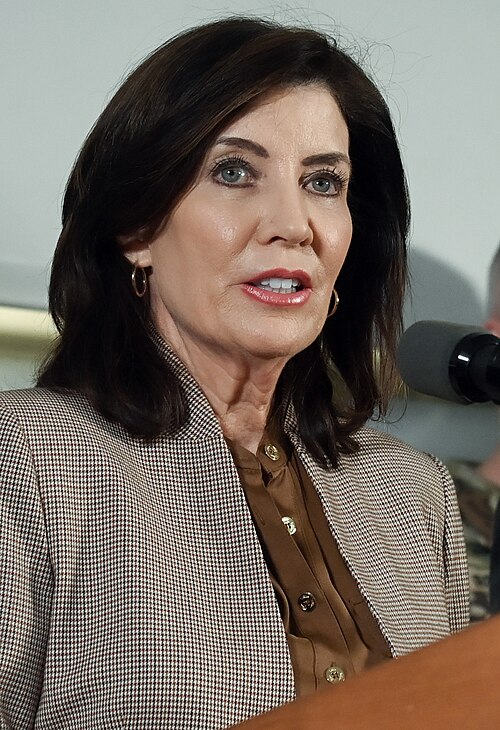

Critics of the pipeline, including more than 100 environmental organizations, allege a quid pro quo in which New York approves the NSEL in return for approval of the wind farm. Weighing at least as heavily on Hochul is the ferocity of anti-natural gas/anti-fracking sentiment in New York, particularly as she plans her 2026 reelection campaign. For now, both approvals remain pending.

Meanwhile, the scope of authority granted under Section 401 remains broad. New York State has permitted several existing pipeline river crossings for both oil and natural gas, as well as some combined sewer overflow discharges and industrial discharges into its waterways. Natural gas pipelines would of course not be intended to discharge to waterways, and methane from a leak into the water is not toxic. But any such leak would constitute a “discharge” under the law, and courts have granted states wide latitude under Section 401.

Whether New York grants or denies NSEL’s application, the result may be litigation — adding to New York’s long and tortured history of grappling with Clean Water Act Section 401. — David Spence

————-

[1] The statute defines a “discharge” broadly to include the addition of any foreign substance into the waterway. Therefore, almost any infrastructure project built over, under or near waterways may cause a discharge.

[2] For a fuller discussion of these early conflicts over certifying hydro projects, see Lisa Bogardus, State Certification of Hydroelectric Facilities Under Section 401 of the Clean Water Act, Virginia Environmental Law Journal, Vol. 12, No. 1 (Fall 1992), pp. 43-101.

[3] For contrasting views of this critique, see here and here.