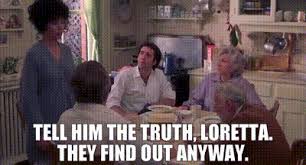

The line in the title of this post comes from the 1987 romantic comedy “Moonstruck,” and the truth at issue in the film’s plot concerns infidelity. But the idea applies to politics as well, and is reflected in the adage that “the cover up is worse than the crime.” So it is with the difficult tradeoffs and value choices that we must make collectively as we transition to a net zero carbon economy.

And over the last five years or so, more transparency has been creeping into the online rhetoric of the climate coalition. Most experts have always known that getting to zero involves complex and difficult decisions about how to balance environmental ambitions against other important public values. But in euphoria of the 2018 “blue wave” election and enthusiasm about a Green New Deal, some activists and experts assumed away (or avoided discussion of) some of that complexity, sometimes even treating those who raised those issues as enemies of the transition. I chronicle some of that in Part 2 of Climate of Contempt.

It was in 2018 that several colleagues and I established the EnergyTradeoffs.com website, dedicated to publicizing and discussing the work of academics who study the nitty-gritty, nuts and bolts aspects of balancing the need for an energy supply that is both reliable and affordable as we transition it to net zero carbon emissions. That website was our reaction to the sanitized rallying rhetoric of the day, and we are currently recording new conversations to be added to that site this fall.

No doubt, the post-2018 setbacks in Congress and the courts have broadened people’s appreciation for the political complexity of the transition. In 2021 Congress failed to pass the Build Back Better bill, which would have imposed greenhouse, gas emissions limitations in the electricity sector. The next year, the Supreme Court struck down the EPA’s use of the Clean Air Act to limit GHG emissions, articulating a new standard of judicial review that probably prevents the use of the existing Clean Air Act to regulate GHGs.

Whatever the reason, there is a growing acceptance among the climate coalition that it is better to acknowledge complexity and difficult tradeoffs openly than to try to persuade voters and politicians by ignoring them. Consider two examples: the adoption of electric heat pumps in place of fossil-fueled home heating systems, and local opposition to green energy infrastructure.

Heat Pumps

Assuming low- or net zero-carbon electricity, replacing oil- or gas-fired home heating/cooling systems with electric heat pumps can go a long way to reducing building sector carbon emissions. Heat pump technology is improving rapidly, but existing heat pumps work efficiently only within a (broadening) range of temperatures. At extremely low temps they switch to resistance heating which uses much more electricity and can become very expensive to use. And they can trigger other significant up front costs when retrofitted on to an existing house.

For a while, it was common for climate influencers and experts to rally others to make the switch to heat pumps by downplaying these limitations, and by accusing those who raised them with trying to derail the energy transition. But in recent years personal testimonials about the cost of installing and using heat pumps have flooded online fora, creating a more realistic picture of that part of the transition. (See e.g., here, here, and here.) It is now easier for non-experts to see that, over their life cycle, heat pumps can be a sensible economic choice for many people, but not for those who live in certain locales or who lack the means to make the up-front investment.

One of the best places to get bluntly honest information about this issue is from a blog called “Nate the House Whisperer.” Nate shares the goal of a rapid energy transition, but doesn’t let that steer his attention away from the difficulties along the path to that goal. Given that broad political acceptance of that goal is the key to reaching it, blunt honesty is the best policy.

NIMBY Opposition

Getting to net zero requires building A LOT of new infrastructure: massive amounts of new generating plants, energy storage facilities, and transmission and distribution lines and associated equipment. And with both political parties pushing to replace imported upstream equipment with domestically manufactured equipment, that means building new mines and manufacturing facilities too.

As with all new energy infrastructure, most of the costs (pollution, noise, visual impacts, etc.) are borne by local communities while the benefits flow to others. Naturally, local so-called NIMBY opposition arises to these projects. Yet it has not been uncommon to see members of the climate coalition denigrate local opposition, either (i) as “astroturf” opposition — a front for companies trying to avoid competition or right wing groups who oppose the transition, or (ii) as a form of “privilege” enjoyed by relatively white or wealthy groups. The truths behind these sorts of claims aim to discredit rather than engage the real locals around whom opposition coalesces. But that is changing as local opposition arises to most of the new projects being built with Inflation Reduction Act subsidies.

The government regulators who make permitting decisions for new energy infrastructure have to deal with those local people and their concerns, regardless of their wealth or the identity of their allies. Ignoring or denying the sincerity and interests local opponents does nothing to persuade those decision makers, and alienates the real, sincere local opponents in the process. Fortunately, we are seeing more and more people in the policy community — indeed, too many to list — who are now advocating respectful engagement of local opponents, and proposing ways to find common ground. This is an important point because sincere, local opposition is ubiquitous (and I have begun collecting news articles to illustrate just how ubiquitous).

With experience comes perspective and wisdom. There is no shortcut through which we can avoid building a broad majority for the energy transition. That is a political challenge. If time is of the essence, we need to elect more climate champions, which implies the need to persuade some skeptical voters. In the long run, we will not fool them by presenting some sanitized or idealized picture of the transition that omits difficult tradeoffs. They will find out anyway. — David Spence