We have known for some time that climate change can increase the intensity and frequency of wildfires. And in recent years wildfires sparked by electric utility infrastructure have become more common. California, Hawaii and Texas have experienced particularly destructive and deadly fires caused by utility poles or lines.

If you contributed money to the relief efforts of the Hawaii Community Foundation after the 2023 Maui wildfire, in March of 2024 you would have received the first of five monthly “thank you” emails. The March note began this way:

Aloha [NAME],

I want to express my sincerest mahalo. You have made a difference for the people and places impacted by the Maui fires with your generous support of the Maui Strong Fund and, most of all, through your aloha for Maui.

“Aloha” is more than just a word; it is a way of life. It means mutual regard and affection and extends warmth and caring with no obligation in return. For the next five months we will introduce the acronym below that demonstrates values that help us achieve aloha—values we see in you!

Akahai

Lokahi

Oluolu

Ha‘aha‘a

Ahonui

This month, we start with Akahai which means ‘kindness expressed with tenderness.’ All of us at HCF have been inspired by the wave of kindness demonstrated by donors like you, from all around the world, to give hope and support to our community in its time of greatest need. …

The tone of these thank-you notes reflects native Hawaiian culture’s communitarian values, something Hawaiians work hard to maintain.

At the same time, the Maui and other wildfires have provoked hyperbolic reactions about the relationship between climate change and wildfire risk. From the pages of the New York Post, former climate science denier Bjorn Lomborg excoriated the New York Times for its “alarmism” (and use of the phrase “a world on fire”) in its reporting on climate and wildfire risk. Lomborg then went on, characteristically, to cherry pick the scientific record to misrepresent the relationship between climate change and wildfire risk. (Indeed, given his prominence in right wing circles, one might be excused for not knowing that Lomborg has no training in the natural sciences. He is, like me, a political scientist.)

The Maui fire was started when heavy winds toppled utility poles, igniting dried vegetation. Climate change did not cause it. But climate change is changing wind and precipitation patterns in ways that increase both the probability of a fire and its intensity. So say the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. As a consequence, these sorts of utility equipment sparked wildfires are becoming a larger problem.

As in Hawaii, the California wildfires occurred against a backdrop of inadequate investment in prevention. My friend Michael Wara and his colleagues at Stanford University’s Woods Institute are doing some of the best work analyzing the relationship between climate change, wildfires and the electric grid. Not surprisingly, there are tough tradeoffs and value choices at the core of these relationships.

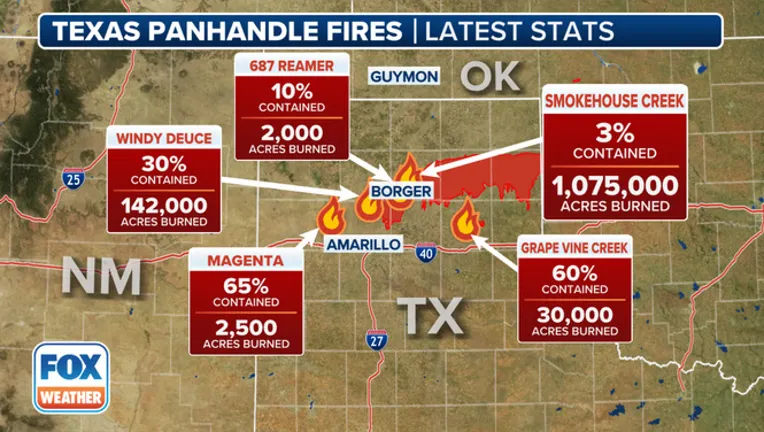

In her terrific book about PG&E and the 2017 Camp Fire, California Burning, Katherine Blunt tells how the utility diverted money and people away from safety inspections on aging transmission equipment and toward other company activities in the years before the first. High winds dislodged high voltage lines from their aged and decaying mooring on a remote electrical tower, sparking the Camp Fire. The same combination – high winds and Xcel Energy power lines – sparked the 2024 Smokehouse Creek Fire in the Texas panhandle, though Xcel disputes the claim that it under-invested in prevention.

Wildfire liability risk plunged PG&E into bankruptcy in 2019. The Maui Fire and Smokehouse Fire triggered sharp drops in Xcel Energy’s stock price and Hawaii Electric’s stock price, respectively. (Both stocks have partially recovered since.) And as of June of this year PacificCorp had agreed to pay more than $900 million to victims of 2020 fires in Oregon.

Preventing wildfires in newly windier, drier remote locations entails some combination of “undergrounding” lines and increased resources and investment in replacing aging above ground infrastructure. Both (either) mean higher electricity rates. Higher energy costs make politicians and policymakers nervous; more importantly, they hurt the most economically vulnerable consumers.

PG&E emerged from bankruptcy bruised but intact. Neither the State of California nor any other private or public organization was willing to take over the utility on terms that could be agreed among the parties. The obligation to keep the lights on, provide universal service, and do so in ways that reconcile those objectives with other public policy and shareholder goals is no easy task.

In some locations, climate change is making it a thankless task. It is one that entails new costs that must be paid by someone, costs that will continue to increase with atmospheric carbon levels. The legal system will sort out questions of liability for the awful damage done by these fires. Preventing them and mitigating their effects is (or ought to be) a collective project. The extreme harm they cause is visited on an unfortunate few, but we cannot predict who they will be.

After the dust bowl, the federal government responded by creating (a) the Emergency Farm Mortgage Act, (b) the Civilian Conservation Corps (which worked on soil erostion), (c) the Federal Surplus Relief Corporation (which diverted surplus agricultural commodities to relief organizations), (d) Frazier-Lemke Farm Bankruptcy Act (which limited the ability of banks to dispossess farmers during recessions), (e) the Emergency Relief Appropriation Act (which provided drought relief established jobs through the Works Progress Administration), (f) the Soil Conservation Service, and (g) the Rural Electrification Act (which brought electricity to rural populations). But as I describe in chapter 1 of my book, Congress was almost a one party institution during the six years of the New Deal. Democrats’ smallest margins were 196 seats in the House and 23 seats in the Senate. And in the 75th Congress (1937-39) the partisan breakdown in the Senate was 76D/16R, and in the House 333D/89R.

Today’s politics are obviously quite different. But regardless, natural disasters can strike anyone, which suggests the need for collective action — a sense of community — to help the unlucky. The final “ALOHA” thank you letter from the Hawaii Community Foundation’s went out a short time ago, and it filled out the acronym:

Akahai – kindness expressed with tenderness

Lokahi – unity

Oluolu – agreeableness and pleasantness in words and actions

Ha‘aha‘a – demonstrating humility

Ahonui – patience and mindfulness

A successful energy transition will require the support of a broad cross-section of the country. For a variety of practical reasons explained in part II of my book, earning that support probably requires more behavior along the lines of these lovely Hawaiian values. – David Spence