Sometimes, in contentious, factually-complex situations, people want simplicity and moral clarity. Those two forces — seeking moral clarity and appreciating complexity — are difficult to reconcile sometimes.

In December of 2023 the presidents of Penn, Harvard and MIT hemmed and hawed when asked by Rep. Elise Stefanik whether advocating the genocide of Jews would violate their campus speech policies. To most outside observers the question seemed simple. To these three leaders, the question may have felt like some sort of rhetorical trap, coming as it did from one of Congress’ most mercenary converts to Trumpism.

The congressional hearing in which the question was posed came only a few months after the October 7 Hamas slaughter of Israeli civilians, and before Israel’s brutal military response. At the time the three university presidents were trying to manage intense campus protests, incidents of violent intimidation against both Muslim and Jewish students, and pressure from donors to crack down harder on protests critical of Israel.

The presidents may have known that some pro-Palestinian protests included the chant, “from the river to the sea,” which can be understood to call for Israel’s destruction. Was that the speech Stefanik had in mind when she referred to “genocide of Jews”? Many academics instinctively resist demands that speech be suppressed, but they ought to have answered the question asked by acknowledging that calling for “genocide of Jews” in so many words is incitement to bigoted violence.

The university presidents are scholars, with all the caution, care and precision that label implies. But they weren’t testifying before Congress as scholars. They were there as institutional leaders. There’s a difference.

When we scholars are acting as in our capacity as educators, we should embrace complexity and nuance in the service of the whole truth. We should be hesitant, and careful to qualify our conclusions with caveats. And we ought to pause and reflect in response to demands that we reduce complex reality to pithy or pat statements.

But today, political polarization and the easy access to wider online audiences pushes us all to abandon careful circumspection in favor of grabby simplifications that might better persuade an audience. We see this in the embrace of scholarship before it has been vetted and accepted for publication. We see it in the way social media selects its public intellectuals, and the insatiable demand for “takes” — especially “hot” ones — on those platforms. Little wonder that some scholars are willing to oversimplify in order to meet that demand for a point of view.

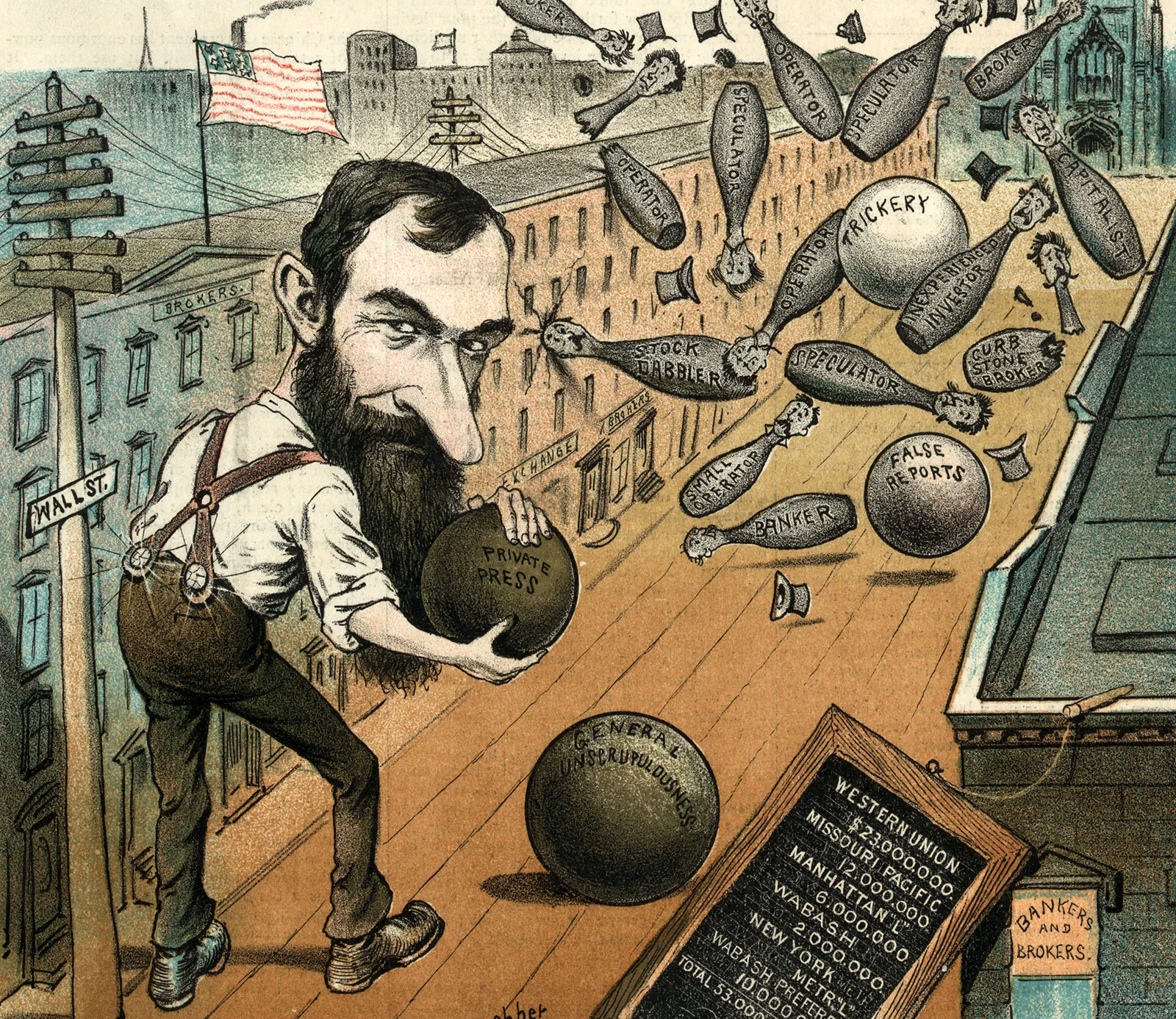

One way this manifests is in meeting the demand of a cynical online public for scholarly support for its cynical views of regulatory politics. At conferences I will hear generalizations like “The railroads wrote the Interstate Commerce Act” or “The Federal Power Act was passed because [utility magnate] Samuel Insull wanted it.” In today’s hyper-populist political environment, politicians play to this cynicism more than ever, portraying themselves as champions of the people fighting against elites.

But as I explain in chapters 1 and 2 of my book, this is not an accurate picture of the politics of policymaking, and it never was. The truth was messier, more complicated.

The historical record shows that railroads intervened on both sides of the fight over the Interstate Commerce Act. Some railroads enjoyed market power in the markets they served, and preferred the status quo. Others faced “ruinous competition” in their markets and sought regulatory relief. Among those opposing the statute were the railroads owned by some of the most powerful Robber Barons of the Gilded Age, people like the Vanderbilt family and Jay Gould.

In the words of one historian, “railroads were not the major advocates behind the [Interstate Commerce Act]”; rather, farm and business interests on both sides of the fight drove the debate.”[1] Another historian called the idea that “railroad corporations . . . supported [Act] as being in their own best interests … historically invalid.”[2]

Likewise, attributing passage of the Federal Power Act to Samuel Insull is equally misleading. During congressional consideration of the law Insull was worried about the prospect of a government takeover of his utilities. He acceded to passage of the statute as the lesser of two evils.[3]

Advocacy and scholarship are two different things. Chapter 5 of Climate of Contempt explains how this temptation to wash away complexity distorts today’s discussion of the many possible technological or policy paths that the energy transition might take. Too often advocates (or critics) of one particular technology or policy fail to interrogate their own side of the argument as fully and energetically as they interrogate the opposing view.

Scholars and other experts should be careful and cautious about their public speech because others rely on them to learn. When a scholarly or news article is designed to persuade more than inform, or if it reads like an attorney’s legal brief, it undermines respect for experts. It leaves readers not knowing who to trust. Policy debate among experts ought not to be like a courtroom, a mere platform for combatants. We ought to acknowledge and address the criticisms of our preferred positions – not simply perfunctorily, or as straw men, but as transparently and objectively as we can.

That’s hard for all of us to do, especially in these politically fraught times. But we have a duty to try. Ours is a cynical age, one in which the information environment makes it difficult for students to learn the whole truth about complex problems. It is the responsibility of experts to help them overcome that difficulty, not contribute to it. – David Spence

————–

[1] Edward A. Purcell, Jr., “Ideas and Interests: Businessmen and the Interstate Commerce Act,” The Journal of American History 54(3): 561-578 (1967), pp.562-564, https://doi.org/10.2307/2937407

[2] Albro Martin, “The Troubled Subject of Railroad Regulation in the Gilded Age—A Reappraisal” Journal of American History 61: 339-371 (1974), p. 339.

[3] Philip J. Funigiello, Toward a National Power Policy: The New Deal and the Electric Utility Industry, 1933–1941 (1973). P. 19; . John F. Wasik, The Merchant of Power: Sam Insull, Thomas Edison, and the Creation of the Modern Metropolis (2006), p. 103.