While we anxiously awaiting the inevitable MAGA assault on climate policy progress and the regulatory state, it doesn’t do much good to react to or comment on it until it actually takes shape. So let me distract you with another observation about a type of misdirected anger I sometimes see online.

In some social media climate communities, opinion leaders sometimes deride grid engineers as a bunch of (white male) risk-averse dinosaurs wedded to the past, slowing the energy transition. They worry too much about the intermittency of renewables. They don’t have enough faith in demand-side, behind-the-meter resources. Etc, etc. (I provide some examples of this in my book.)

I am not an engineer but I have worked with engineers on energy and environmental issues for most of my adult life. In Climate of Contempt I describe grid engineers as problem solvers for hire. They will find ways to solve the problems that policymakers present to them.

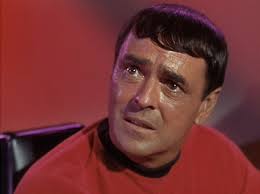

Yes, they are sometimes too worried about or skeptical of drastic change. This characteristic was captured in the Star Trek character, Chief Engineer (Montgomery Scott). In various iterations of the Star Trek franchise, “Scotty” repeatedly claims that the tasks he is asked to perform are impossible, but he almost always comes through in the end.

So it has been with grid engineers. For almost a century their job was to provide customers with reliable, affordable power. That began to change about 60 years ago when we started to care more about the environmental impacts of how we generate and use power. Today that environmental focus is on climate and carbon emissions, and rightly so. Consequently, most grid managers must try to provide affordable reliable power with a minimum of climate impact. And in states that have mandated a path to net zero carbon emission in the electricity sector, engineers are working to reconcile electricity reliability with that goal.

At one time, grid engineers didn’t think they could integrate nearly as much weather-dependent renewable power as we do now. But they found a way. And they are currently finding ways to make better use of behind the meter resources. They will figure it out.

Take a look at this short Twitter/X thread from a British power systems engineer. It reflects the kind of thinking I am used to seeing from engineers. The author is proud of the way engineers solved problems in the past, and he sounds eager to take on the challenges of the future. He is positively nostalgic about coal-fired power plants as engineering marvels, but realistic in acknowledging that their day is past. They emit far more deadly pollution and more greenhouse gases than other generating technologies, and those other lower-emitting sources can now do what those old coal plants did less expensively and just as reliably.

The future requires managing this energy trilemma* in an rapidly changing techno-economic and policy environment. Defining the right balance is a question for policymakers, and they answer it differently in different places. Once they choose a balance, grid engineers will try to find the best mix of options that supply that requested balance.

Since Congress has refused to regulate greenhouse emissions, state and regional policymakers are free to prioritize any one of these values over the others. Some policymakers want energy to be as inexpensive as possible. Some err on the side of protecting reliability.** And increasingly, many want the energy system to be as clean (or low carbon) as we can make it. While engineers warn that pressing too hard on any one goal puts pressure on the others, they also seem to find ways to manage those tradeoffs better than they expected to.

So when engineers warn us about these tensions and tradeoffs, they are helping us see problems more fully — not doing the bidding of enemies of the transition. At worst, they may simply be underestimating their own ability to solve the problem. And when their solutions don’t allow us to have our cake and eat it too, they don’t deserve scorn. They are doing what their policymaker overlords ask them to do.

Because technological progress moves in one direction, the technical aspects of the energy trilemma will get easier to manage over the long run (even if we can’t predict, how, where, or when that will happen). That is reason for hope about the energy transition in perilous political times. So raise a glass to grid engineers, who will play a big role in figuring out how to make the transition work. — David Spence

—————-

*A Google search will tell you that this term was coined by the World Energy Council in 2010, but I first saw it in a law review article in 2008. See John A. Sautter, James Landis, and Michael H. Dworkin, The Energy Trilemma in the Green Mountain State: An Analysis of Vermont’s Energy Challenges and Policy Options, 10 Vt. J. Envtl. L. 477 (2008).

** Some portray policymakers who prioritize cost or reliability as duplicitous, using those goals as cover for delaying the transition or the corrupt influence of utilities or fossil fuel interests. I have explained elsewhere (and at length in my book) why this is a leap of logic — and an inaccurate one as a generalization. The simplest reason policymakers prioritize things that way is because voters prioritize reliability and affordability over environmental impact.