[NOTE: This is the first of two posts about taking care when drawing political lessons from the election results. The second will appear here on 11/11. — DS]

———-

When Democrats lose elections it is common to see immediate, impulsive “takes” from all sides of the party, most explaining how “my theory of politics” was vindicated by the results. And so already we see some blaming Democrats’ “abandonment” of the working class, or Harris’ reluctance to more strongly oppose Israel’s war in Gaza, or racism on the part of White women, or misogyny on the part of Black and Hispanic men, or liberal elitism (see here and here), or big money control of politics. Indeed, one can spin plausible versions of many narratives from the exit poll results.

Why? Because every voter’s voting decision has multiple drivers, and each set of drivers is unique (and uniquely weighted) to that voter — her values, the information she has consumed, her social environment, etc. Pundits (professional and otherwise) analyze the election returns looking for trends in aggregate voting results, or within demographic or other subsets of the vote totals. When pundits identify trends or tendencies of a particular group of voters, other people sometimes understand them as a generalization that applies to all the members of the group.

If we don’t like the trend, we may express displeasure with that group of voters as a group (e.g., “White women” or “Hispanic men”). Before social media, those careless-if-human reactions would be heard only by a few friends or family. Now they are broadcast to a much wider audience where they can alienate members of the group to whom the generalization doesn’t apply. As Ricky Gervais once observed, “Twitter is like being able to read every [bathroom] wall in the world.”

So in a sense, all the pundits are correct. Each diagnosis describes some subset of voters. At the same time, all are incorrect as descriptions of entire demographic groups. But we can only know their importance as drivers of votes based upon more rigorous, careful study. So “hot takes” should be viewed with skepticism.

Let’s look at the arguments crediting racism, sexism and misogyny first.

VP Harris’ 2024 vote total (68.1 million) was more than 13 million votes fewer than Joe Biden received in 2020 (81.3 million). Indeed, Donald Trump’s victorious 2024 vote total (74.2 million) was also less than his 2020 total (74.2 million). Furthermore, down-ticket Democrats tended to outperform Harris, and she lost ground among young men (compared to Biden). Voters supported local propositions in many states favoring Democrats’ priorities, like strong climate policy and protecting abortion rights.

All of which could suggest that it was something about Harris (race, sex) that alienated some voters. Some read exit poll and anecdotal data showing that Hispanic men broke for Trump, or that white women broke for Trump, as evidence of misogyny and racism, respectively. But is that a solid inference?

Might it also be that many of these voters blamed the Biden-Harris Administration for the inflation they experienced or the immigration crisis at the border — or that they preferred non-traditional candidates (like Trump) over “professional politicians”? I despise Trump’s inaccurate, defamatory, fear-mongering descriptions of migrants, but for the first time in over 100 years the Texas Rio Grande border counties voted for the Republican candidate. Many of these voters are Hispanic people who experience the border crisis first hand. They may understand that Trump is lying AND believe that the current administration has not handled the problem well.

Some pundits blame Democrats’ embrace of progressive cultural norms. What about that hypothesis?

GOP candidates across the country campaigned against “woke-ism,” reflecting their belief that it was a winning issue. In Ohio in late October I saw a barrage of TV ads for Bernie Moreno, who flipped Sherrod Brown’s senate seat from red to blue last week. Moreno’s ads ended with tag line “Bernie Moreno is for you. Sherrod Brown is for they/them.” Did anti-woke-ism gain votes for Republicans? Perhaps. See, for example, this paper showing (through various empirical studies) that opposition to anti-racism is a force distinct from racism, and a better predictor of white voter support for Donald Trump than measures of implicit or explicit racial bias.

These sorts of results echo claims by moderate Democrats that the “defund the police” slogan hurt the party in competitive districts in 2020. For Democrats who believe that more inclusive gender norms make for a kinder world, or that antiracism can address a lingering social problem, the question is this: Do we ascribe white voters’ aversion to these ideas to their moral failures? Or do we engage those voters in a search for more effective ways of achieving a kinder, fairer society?

What about the claim that Harris lost support because she was insufficiently pro-Palestinian when discussing the Gaza war?

The data in Michigan, a key swing state with a high percentage of Muslim voters, show that those voters broke for Trump. And perhaps some of Trump‘s considerable gains among young voters may have been expressions of dissatisfaction with the Biden Administration’s policies in the Middle East. Or maybe this, along with Harris’ more moderate campaign positions, contributed to low turnout among progressive young people. If so, all of those voters may be in for a rude awakening. It seems highly unlikely that a second Trump administration will be less supportive of Israel than the Biden administration was.

What about the idea that the election results were mainly a generalized expression of anger at comfortable, urban, liberal elites?

My book offers some support for this proposition in its discussion of research showing that wealthier, white urbanites lead the most politically isolated lives. It may be that the Trump campaign, with a big assist from social and ideological media, was able to steer voters’ sense of economic and cultural inequality toward a sense that sophisticated, urban, liberal elites disdain them. Whether or not that is true, it is not hard to imagine why it might have resonated.

Cities run by Democrats are filled with educated urbanites pursuing interesting, well-compensated work and living fulfilling lives. Their NIMBY opposition to high-density housing effectively excludes from their communities many of the people who make those interesting lives possible: the nurses who provide them with healthcare, the Uber drivers who move them around, the people who clean up after them and maintain their streets and sidewalks, and the clerks who sell (or deliver) their groceries. Those nurses, drivers, and clerks endure long daily commutes to do their jobs, and have less time with their families as a consequence.

Democrat Andy Kim, who won his race for New Jersey’s senate seat, offered some support for this idea. In a thoughtful Twitter/X thread last week, Kim credited his own constituents’ “disgust” with politics and politicians to Democrats’ political isolation and indifference. His prescription echoes chapter 6 of my book:

There is too much hubris in our politics. Too many people who think they have all the answers. Let’s go out and have deep and thoughtful conversations with people. Listen to them. And then earnestly work to address their concerns and rebuild trust.

In a tweet on Nov. 6, Senator Bernie Sanders blamed “the Democratic Party” for “abandoning” working class people. It’s not clear if Sanders was trying to echo Kim’s point, of if he was aiming his criticism at the Biden-Harris Administration. If the latter, his tweet makes little sense. No administration since FDR has been more pro-union or embraced muscular government spending to promote the creation of manufacturing jobs than the Biden-Harris Administration.

What about the idea that the election demonstrates the power of corporate money to drive election outcomes?

This claim is also inconsistent with the facts. By every measure, the Harris campaign significantly out-raised and out-spent the Trump campaign — in swing states and everywhere else, on advertising and on the so-called “ground game.” From January 2023 to October 2024 Biden-Harris campaign committee raised $997.2 million and spent about 85% of that money; the Trump’s campaign committee raised $388 million and spent about 90% of that total. Before the election most observers were touting the overwhelming superiority of Harris’ canvassing and ground organization.

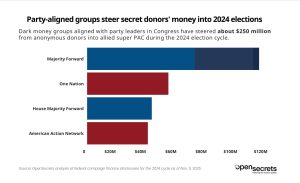

Nor did dark money favor Republicans; to the contrary. This chart (above) from Open Secrets documents the sizable advantages Democrats enjoyed among dark money groups. This is consistent with the political science literature I review in Climate of Contempt. It just isn’t true that money controls outcomes, especially in today’s information-congested environment.

What about the propaganda machine?

I would be remiss if I didn’t note that these data can be fit to my propaganda-based explanation too. As the New York Times put it a couple of days ago, Trump’s “essential bet” was they he could leverage voter frustration and rage into votes by talking incessantly about grievances, both real and imagined.

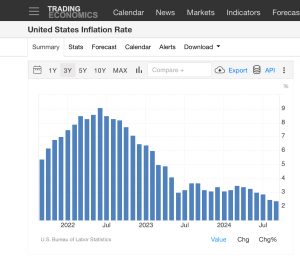

For example, it is a fact that inflation was triggered everywhere by lag between post-COVID resurgence of consumer demand and restarting global supply chains, that the U.S. economy handled those forces better than most other economies, and that the Fed got inflation under control in late 2024. But people believed otherwise.

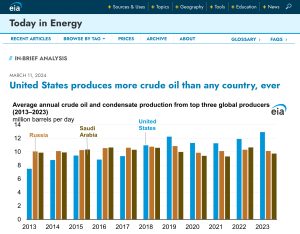

It is a fact that under the Biden Administration the U.S. has produced more oil than ever in U.S. history, and more than other producers in the world. But some people believed otherwise.

And there are many other disconnects between facts and voter beliefs that may have helped Trump, on all sorts of issues from vaccines to gender. We know from the research I summarize in chapter 4 of my book that social and ideological media foment resentment and grievance, and cultivate and maintain false beliefs, hyper-efficiently.

Conclusion?

So, election results can be fitted to more than one narrative about what drives political outcomes. But we don’t need to place blame on any one thing. It is human nature to want to do so, and to do so in ways that confirm our prior beliefs — especially when emotions run high.

Nor are the emotions the problem. No one should accept with equanimity the election of a venal, intellectually lazy, narcissistic adjudicated rapist who promises to take a wrecking ball to the foundational institutions of American democracy — even if the threat to democracy didn’t resonate with voters. Donald Trump is a convicted felon facing still more criminal indictments. He committed a crime in 2020 when he pressured states to send GOP electors to the electoral college in place of the Democrat electors selected by voters.

But while fearing a transition to authoritarian government is reasonable, jumping to conclusions about voters is not. We need to be circumspect, and to appreciate the multiplicity of reasons different voters have for their votes. Blaming White women, Hispanic men, Generation X, or any group of people for an unwanted outcome ignores that complexity, and disrespects some members of those groups.

So try to read all the election takes, including this one, with a critical eye. Pay more attention to data and less attention to invitations to draw specific inferences from them. Meanwhile, Andy Kim’s advice (quoted above) about avoiding hubris and engaging others can’t hurt the cause of the energy transition.—David Spence