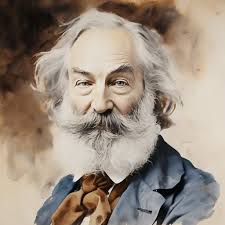

“America, if eligible at all to downfall and ruin, is eligible within herself, not without; for I see clearly that the combined foreign world could not beat her down. But the savage, wolfish parties alarm me. Owning no law but their own will, more and more combative, less and less tolerant of the idea of ensemble and of equal brotherhood….” — Walt Whitman, 1870

When I was writing Climate of Contempt, I found more useful quotations than I could possibly include in the book. They came from philosophers, writers, scholars and politicians, all capturing different aspects of the troubling political pathologies that I discuss in the book. Many of those warnings predated the modern social sciences, illustrating that perceptive philosophers, writers and politicians have long had an intuitive sense of how important these phenomena are, and how fragile our liberal democracy is.

One quote that I hadn’t seen before writing the book is the passage above, from Walt Whitman‘s “Democratic Vistas” (1871). (Thanks to my friend Jeff Clark for bringing it to my attention.) In it, Whitman zeroes in on the pathology that most threatens American democracy today: namely, the set of biases that close our minds to opposing views and so steadily strengthen inter-partisan animosity. In my book I illustrate this idea using quotations from mid-20th century jurist Learned Hand, philosopher Karl Popper, and academic psychologist Jonathan Baron.

These voices are emphasizing that both halves of the phrase “liberal democracy” are worth worrying about. Because democracy can destroy democracy.

American democracy depends upon cross-party respect for truth-seeking, the rule of law, fair political competition, the peaceful transfer of power, and pluralism. It needs a critical mass of people who can accept unwanted outcomes as legitimate as long as they are produced through a fair process, and whose reasoning skills allow them to distinguish between their preferred outcome and a fair process. That is, it cannot survive in an environment in which the losers of an election or policy fight routinely or reflexively claim that it must have been the result of an unfair process.

The November election is behind us, but this threat to our liberal democracy remains, sustained by ideological and social media, which constitute the most powerful propaganda machine in human history. The norms on which we rely to sustain respect for pluralism are eroding, steadily.

When Donald Trump pardoned relatives and close associates who committed crimes, it became easier for Democrats to excuse Joe Biden’s pardon of his son. And because so many GOP voters regard the criminal prosecutions of Donald Trump as political persecution, it will be easier for GOP voters to excuse the use of the FBI and Justice Dept. to persecute Trump’s political enemies, should they make good on those promises.

It is a vicious cycle. Each breach of traditional democratic norms by one side feeds fear, anger and resentment in the other. Sophisticated propagandists (read: ideological media) tell us continuously that the worst of the other party is typical of that party. For now, it it looks as though online subcultures will continue to breed ever more intense fear, anger and resentment of political adversaries.

It is not a prescription for a happy new year, or for a happy future beyond 2025. So let’s make it happier (or less unhappy) by talking to people across partisan and ideological boundaries — not about partisan politics or politicians, but about the issues you care about. Not accusatorily but inquisitively.

Chapter 6 of my book summarizes the advice of many experts from a variety of fields on the challenge of sustaining communication amid disagreement, and there is a surprising amount of agreement on this issue. Ask people why they believe what they believe, and why they favor the policies that they favor. When they answer, don’t respond with reasons why they are wrong; think instead about how or why they came to that belief system. Think about their fears and biases — empathize — and keep the conversation going. And do it in person. Bilateral, private conversations are much more likely to be productive than online, public conversations.

And remember that even in private conversation the other person may come to the conversation with trepidation or insecurity, and that (what Cook Political Report calls) “the diploma divide” looms over political dialogue like a dark cloud.

My late father-in-law was orphaned at a young age in a tough Boston neighborhood. He enlisted in the Air Force while in his teens, became a sergeant, and served for 20 years. He was one of the sweetest people I have even met — a generous, giving soul. I miss him. But when I was in grad school he was inclined to tell me the following joke:

You know what B.S. stands for, don’t you? Well, M.S. is “more of the same,” and Ph.D is “piled higher and deeper.”

If your family or friends regard you as the over-educated smartypants, or member of the coastal urban elite, don’t let that stop you from talking to them about climate change and energy. But try to see things from their point of view when you do.

As a matter of climate activism, what have you go to lose? Angry online ridicule of climate “denial and delay” doesn’t seem to be persuading voters to prioritize this issue in their voting decisions. These conversations across political (and cultural) boundaries, when approached with respect and care, can be very rewarding. You might learn something. And you might become the counter-example that bursts someone’s hateful misconceptions about a group that their media bubble demonizes.

Again, countless quotations make this same point, many of them from song lyrics. “Reach out and touch a hand.” “Talk to every stranger, the stranger the better.” And so many more.

In Climate of Contempt I repeat over and over the statement that “it is unfamiliarity the breeds contempt.” So don’t let the propagandists be the only source of information about politics and policy for your friends and family. Talk to them, and let’s make a happier 2025 and beyond. — David Spence