For some people, complex ideas resonate more when conveyed through artistic expression than through narratives or numbers.

Many readers will have heard of energy historian Daniel Yergin’s book, The Prize. Fewer will know his sequel, The Quest. In the latter book Yergin tells the story of how a petroleum engineer named Luis Giusti tried unsuccessfully to persuade then-Venezuelan president Rafael Caldera that the country would benefit from opening Venezuelan oil markets to foreign investment. Reports and data failed to move the president.

Then [Giusti] had an idea. Why not actually paint a picture? He knew a brilliant geologist who was also a talented landscape painter, Tito Boesi. … [Giusti] called Boesi and said that he wanted the geologist to paint a large canvas mural … The purpose would be to vividly demonstrate how increasingly complicated and expensive would be the further development of Venezuela’s petroleum patrimony [without foreign capital]. …

When Giusti [later presented the painting], he could see that President Caldera was angry. At first he thought it was directed at him, but then he realized that Caldera was angry with his own entourage, which, the president concluded, had not briefed him on the scale of the challenge facing the industry on which Venezuela depended. (pp. 120-121.)

In my book I talk a little bit about the role of art in influencing perception of energy issues: for example, The Simpsons influenced perceptions of nuclear energy, as did activist musicians. Some entertainment industry portrayals of fracking and climate change have been activist projects. But more than any other artistic medium, music has consistently been linked throughout modern history with social commentary, including commentary on energy and environmental politics.

Popular music includes songs expressing virtually every important idea or sentiment discussed in Climate of Contempt — environmental worries, laments about the destructive effects of modern media, and anthems that protest dysfunctional U.S. politics.

Like physical exercise, artistic expression can be an outlet for the strong emotions that can distort our perceptions of the energy transition – a place where figurative primal screams do less damage than they do in popular political debate. (Like millions of other hobbyist songwriters, I have channeled my own frustrations about politics into song lyrics.)

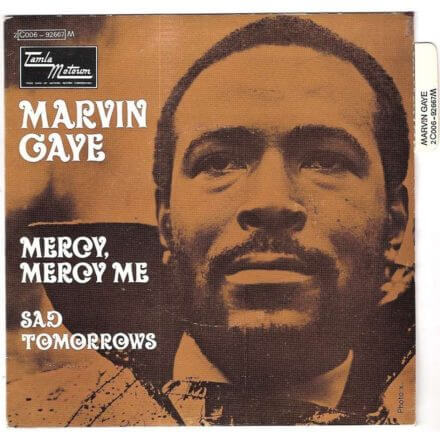

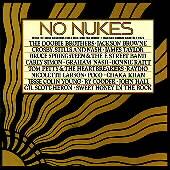

This website includes a link to a playlist of songs that address many of the ideas and sentiments that are discussed in Climate of Contempt in more clinical language. There are about 60 songs in all. (The list could include many more, but my musical tastes limited its size.) They include Marvin Gaye’s iconic environmental anthem “Mercy Mercy Me,” and a 1970s anti-nuclear power anthem “Power,” by musician-turned-congressman (turned-musician-again) John Hall.

But some of the lesser-known songs on the playlist speak most directly to the themes of the book. Rising Appalachia’s song, “Resilient,” includes the lines “I’ll show up at the table, again and again and again / I’ll close my mouth and learn to listen.” Readers of the book will recognize this sentiment from the Chapter 6 discussion of social scientists’ endorsement of this kinder approach to politics. That literature suggests that “the nascent social movement seeking to strengthen democracy in America … can reduce political sectarianism [and] produce a body politic that increasingly prioritizes democratic means over partisan ends.” I noted in an earlier post Barack Obama’s admonition that “our fellow citizens deserve the same grace we hope they’ll extend to us.” Obama was echoing this same idea.

In 2023 Illinois Gov. J.B. Pritzker — after whom the Northwestern University Law School is named — gave a graduation speech in which he said this:

When we see someone who doesn’t look like us, or sound like us, or act like us, or love like us, or live like us, the first thought that crosses almost everyone’s brain is rooted in either fear or judgement or both. That’s evolution. We survived as a species by being suspicious of things that we aren’t familiar with. In order to be kind, we have to shut down that animal instinct and force our brain to travel a different pathway.

Empathy and compassion are evolved states of being. They require the mental capacity to step past our most primal urges. This may be a surprising assessment because somewhere along the way in the last few years, our society has come to believe that weaponized cruelty is part of some well-thought out Master plan. Cruelty is seen by some as an adroit cudgel to gain power. Empathy and kindness are considered weak. Many important people look at the vulnerable only as rungs on a ladder to the top. I’m here to tell you that when someone’s path through this world is marked with acts of cruelty, they have failed the first test of an advanced society. They never forced their animal brain to evolve past its first instinct. They never forged new mental pathways to overcome their own instinctual fears. And so their thinking and problem solving will lack the imagination and creativity that the kindest people have in spades. … The kindest person in the room is often the smartest.

These are beautifully-expressed and profound ideas. But in today’s cynical, identity-focused political environment, some people may not be willing or able to hear them from Pritzker, either because he is a politician or because he is a very wealthy man (his family owns Hyatt Hotels). Maybe for those people music conveys these kinds of ideas and sentiments in ways that resonate better.

The title of this post comes from a line in another song on the linked playlist, “Kindness” by Ryan Adams. It expresses with simplicity the value of withholding presumptuous anger in human relations, including political relations. A social life lived online makes the world seem less kind than it actually is. So, it helps if we can get away from those influences. And perhaps music can help make the case for a restoration of a better-functioning democracy. – David Spence