In Climate of Contempt I lament the way today’s political information environment breeds so much interpartisan fear, anger, and distrust that we “under-attend[] to the health of our democratic institutions.”[1] But one thing I did not do in my book was to describe today’s GOP as “fascist.”

I have avoided that label up to now for three reasons. First, there is popular confusion about what the word means (see more below), just as there is with the term “socialist.”[2] Second, the term evokes historic Nazi cruelties that the Trump Administration, despite its own conspicuous cruelties, has not matched. And third, I am old enough to remember how loosely the word “fascist” was thrown around by the activist left in the 1960s, and don’t want to contribute to that sort of rhetorical sloppiness.

But since my book came out (August 2024) the second Trump Administration has weakened or destroyed liberal democratic institutions with amazing breadth and speed, abandoned century-old traditions of good governance in the executive branch, and has empowered white nationalists in ways that mimic prior transitions to fascism. With refreshing candor, Donald Trump has admitted his belief that some people “want a dictator,” and that he can do “anything I want.”

Consequently, in even in relatively sober online platforms like LinkedIn and Substack, my feed includes more and more content premised on the notion that the GOP is fascist. So, it’s time to reexamine the wisdom of applying the “fascist” label to today’s GOP.

What is fascism?

Some dictionaries recognize the looser ways in which many people use this term. The Oxford English Dictionary, for example, includes multiple definitions, one of which is “any form of behavior perceived as autocratic, intolerant, or oppressive, … [or] that seeks to enforce conformity.” (Emphasis added.) But political fascism is narrower than that, and this broader definition would include all sorts of behavior on the populist right and left that is unrelated to the use of government power.

Merriam-Webster defines fascism this way:

a populist political philosophy, movement, or regime … that exalts nation and often race above the individual, that is associated with a centralized autocratic government headed by a dictatorial leader, and that is characterized by severe economic and social regimentation and by forcible suppression of opposition.

The Cambridge Dictionary is similar, but a bit more succinct: “a political system based on a very powerful leader, state control, and being extremely proud of country and race, and in which political opposition is not allowed.”

Do these definitions fit the Republican Party of 2025?

The Trump Administration, with assistance from the Supreme Court, has pursued the centralization of power and suppression of political competition with considerable success (so far). It has destroyed the tradition of nonpartisanship at the Department of Justice and FBI, using both agencies as instruments of the president’s personal political vengeance in ways that would make Richard Nixon blush. It has promoted a cult of personality around the president in part via televised cabinet meetings that are positively North Korean in their performative sycophancy. It has significantly weakened the capacity of executive branch to “faithfully” execute laws — laws that congressional Republicans were unable to repeal or weaken by statute. It has punished whistleblowers at EPA and FEMA, and fired the government ethics officers in charge of whistleblower protection. And Trump has personally demanded that GOP states engage in mid-decade gerrymandering in order to skew future electoral results in the party’s favor, setting off a gerrymandering arms race in the states.

The GOP has not outlawed opposing parties or put potential candidates in jail. Nor has Trump declared martial law or canceled elections to extend his reign (though some see his deployment of federal troops to major cities as a precursor to that). But he is open about seeking suppression of partisan competition in subtler ways.

Likewise, the two Trump presidencies have invigorated nativists and white nationalists within today’s GOP in ways that resemble the dictionary definitions of fascism, even if they fall short of Nazi-like attempts to exterminate people. The president’s own history of racism is sufficiently extensive to merit its own Wikipedia page. And academic investigations support the idea that right-wing media “primes” voter racism. So things like deporting immigrants to hellish locations other than their countries of origin, evading court-imposed limits on the persecution of immigrants, and the opening of the “Alligator Alcatraz” detention center can be seen as a kind performative cruelty that is only partly about deterring immigration, and partly about pleasing bigots in the party’s base.

Today, the MAGA faithful are dictating GOP policy, and like the fascists of old many are fueled by a deep, long-simmering sense of being left behind culturally and politically, and and of being looked down upon by the urban, intellectual left. Ideological media fan those resentments 24/7, and they eventually fester into group hatreds. That, in turn, makes partisan retribution popular with the resentful base.[3]

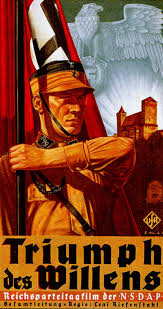

That sense of grievance and victimhood was also characteristic of 20th century fascists. Most of the world experienced the Great Depression in the 1930s, but only a few countries turned to fascism. The economic oppression visited on a defeated Germany by the Treaty of Versailles prepared the ground for a demagogue who pointed the finger of blame at Jewish economic elites. Italy was among the victors in WWI, but Italians resented their loss of territory and colonies under the Versailles Treaty, a resentment Mussolini cultivated and exploited. Propaganda also played a role in those demagogues’ rise.

But of course, there are degrees of fascism. Indeed, one of the reason critics apply the word to adversaries is precisely because it evokes the Holocaust, which gives it extra sting. Today’s GOP has not (yet?) exhibited that same degree of depravity as 20th century fascist regimes. And while some of the damage it is doing to the rule of law is irreversible (e.g., pardoning more than 1500 convicted January 6th insurrectionists), some of it will eventually be overturned by the courts. Some GOP politicians say that they are troubled by the Administration’s actions, but in today’s bitterly-divided, hyper-partisan, post-truth era, all that really matters is how people vote — how members of Congress vote, and how (and whether) citizens vote. So far, neither Republicans in Congress nor Republicans in the electorate have risen up against Trump’s dictatorial agenda.

So, if we stick to the dictionary definitions listed above, today’s GOP is at least “fascist-ish.” Indeed, at this point few observers would be surprised if Trump were to flout the 22nd Amendment by running for a third term, or even if most Republican politicians were to support that decision.

Semantics vs. Political Strategy

So it seems intuitive that we ought to condemn these lurches away from representative democracy, openly and in the strongest possible terms. Some people believe that it is already too late to recover our democracy, so why not call a spade a spade? Others place hope in “soft secession,” coordinated efforts by Democratic governors and mayors to resist movement toward fascism through noncompliance with federal edicts.[4] A growing segment of the left believes it is naive to adhere strictly to the law while the other side flouts it: that only by mirroring GOP departures from democratic norms can we win power and restore those norms. And watching the national party accede to Trumpism (and the Supreme Court facilitate some parts of it), it feels honest to call the GOP fascist.

These are understandable views, so I don’t begrudge anyone calling today’s GOP “fascist.” But the question in the title of this post is not simply a semantic one. It is also a strategic one. Calling the GOP “fascist” may mobilize activists on the left, but it is not an essential part of firm resistance to fascism. And in today’s informational environment it may also alienate parts of the GOP coalition whose votes are particularly pivotal in today’s national elections (for reasons explained previously in this space).

Today’s GOP includes more than the MAGA faithful. It also includes (a) cultural and economic conservatives who understand the ongoing damage to democracy, but go along for policy reasons, as well as (b) the less engaged voters who are either unaware of or indifferent to the GOP’s de facto embrace of authoritarianism and white nationalism.

Of course, the fascist regimes of the 20th century also included passive enablers, and we now regard those enablers as complicit in atrocities committed by those regimes. However, Hitler and Mussolini completed the transition to fascism, but the United States is still traveling along the transition-to-fascism curve. The trick for the autocrat is to centralize power [read: effectively weaken or rig legal and electoral institutions] before his vengeful policies jeopardize the autocrat’s hold on power by alienating the rest of his electoral coalition. Hitler and Mussolini threaded that needle, but today’s MAGA-led GOP may not yet have done so.

Stopping that process peacefully depends upon those other two parts of the GOP coalition. Without their votes that cannot be done. Does it help the cause to call them fascists, or complicit in the transition to fascism? A growing number of Democrats believe that doing so is a necessary part of “resistance” or “fighting back.”

Let me explain why I disagree.

Let’s think first about the less engaged voters. Thirty years ago many of them would have heard (from mainstream news) about the worst of the autocrat’s behavior. Indeed, that drip-drip-drip of ugly truths eventually sank Richard Nixon’s presidency, even though Nixon’s transgressions were far less numerous or dangerous to democracy than what the Trump Administration is doing now. But today those same low information GOP voters will not learn the ugly truths about their party. They don’t know which news to trust, and any “news” they consume is likely to sugarcoat ugly truths about Trump Administration actions, or omit them altogether in favor of stories covering things those voters don’t like about Democrats and the left.

And what about the go-along conservatives? Whether we agree with them or not, many go-along conservatives do not (yet?) believe that their party can be properly described as fascist. Many believe that the legal system will eventually restore the democratic norms the Trump team is currently trampling (which is likely to be partly true). And most are alarmed by renewed talk of packing the Supreme Court or the Senate. If that is what “soft secession” means, it scares them.

So, when these groups hear people applying the fascist label to their party (or to them), it sounds hyperbolic, or like sour grapes. Worse, ideological and social media sorts that “news” in ways that instantly weaponizes that sort of language. It turns both real and perceived hyperbole against the speaker, reversing its net persuasive effect. (Chapter 4 of my book cites a series of social scientific studies explaining this phenomenon.)

Silence is not the answer

Still, no one wants to remain silent as this transition toward autocracy continues. Nor should they. We can all engage the non-MAGA parts of the GOP coalition in discussions about the many, specific, unpopular actions taken, and policies embraced by the Trump Administration. Senate Republicans who claim to care about public health, sexual assault in the military, the gutting of FEMA and the EPA, and the professional integrity of the intelligence community, FBI, and the Justice Department voted to confirm executive branch nominees who are (predictably) undermining those values. Senators who claimed to champion the constitutional right to an abortion voted to confirm Supreme Court justices who destroyed that right. These are the specifics that many of the non-MAGA GOP voters dislike, but do not hear much about from right-leaning advocacy news outlets.

So, we can talk to our friends, family, neighbors and co-workers about those things, preferably in as empathetic and civil a way as possible. We can contest these objectionable actions without labels that express contempt for entire groups of people. We can be the source of the drip-drip-drip of ugly truths that ideological media hides from GOP voters. In short, we can leave our Republican friends and family the emotional space to change their minds.

In my book I describe the research supporting the value of this sort of patient, bilateral dialogue, but I also describe that path as the best nonviolent path to restoring democratic norms. Violent paths are certainly possible; indeed, they are looking more and more likely. Blue states and cities have few options left except soft secession: i.e., coordinated noncompliance with federal orders, protests, and the like. A Trump Administration emboldened by a compliant GOP and Supreme Court seems likely to respond with force. Therefore, we may not be far away from the kind of constitutional crisis seen in other, supposedly less stable democracies, one that turns on the question of “which side” the army (or police, or national guard) chooses to support.

Given all that, calling the GOP “fascist” seems less important than being resolute and strategic about pursuing the best hope for a peaceful restoration of democratic norms. At least it does to me. But after the last six months I can see why reasonable others might disagree. — David Spence

——————–

[1] Climate of Contempt, pp. 19 & 25. Of course, writers like Timothy Snyder and Anne Applebaum have been ringing these same warning bells for some time; my book’s contribution was to show how these forces distort our understanding of the energy transition.

[2] Climate of Contempt, p. 25.

[3] There is an analogous group hatred problem on the left, one that seems to be manifesting in more personal ways. But when it comes to voting behavior, the MAGA segment of the GOP electorate is much bigger and more powerful within the party than the mirror image negative partisans on the left.

[4] “Soft secession” is a nice term for Democrats engaging in mirror image actions — competitive gerrymandering, abandoning other good governance norms — that hurt democratic institutions in furtherance of Democrats’ electoral and policy goals, one of which is ostensibly the reestablishment of democratic norms. Troublingly, some versions of this rely on pre-Civil War views of state nullification of federal law that we have considered invalidated by the war and the amendments to the Constitution that followed it.