The parties’ nominating conventions are over and their platforms set. The GOP platform emphasizes “energy dominance” and doubling down on fossil fuels. (And see my previous posts discussing the energy particulars of Project 2025 here and here.) The Democratic platform leans into Inflation Reduction Act-style green energy subsidies. And while some pundits are predicting that Kamala Harris will meet or exceed Joe Biden’s considerable climate policy ambitions, Harris has not articulated that bolder climate policy message in her campaigning to date, disappointing some climate activists. Presumably both parties are tailoring their appeals to (what they believe are) voter preferences.

As most people know, winning presidential elections is about capturing the most electoral votes, not winning the popular vote.* So electoral math is mostly about key states that are “in play” — those where either party could win. In some places, no doubt, bold messaging rallies the base to turn out and provide the margin of victory. But not everywhere — which is why national messaging is complicated and fraught.

A national party’s positions and ideas may be relatively unpopular within particular congressional districts or states. So, maximizing electoral outcomes across different races at the same time can be tricky. Over the last few electoral cycles, moderate Democrats in the House of Representatives have complained that progressive messaging on policing and cultural war issues damaged their standing with moderate swing voters.

That may be why House Democrat Jared Golden, who represents a Maine district that Cook Political Report rates as more Republican than Democrat, recently promised to fight his party’s leadership on climate, and to “reject party loyalty, the idea that there should be some kind of national party with a series of cascading litmus tests and everyone’s gotta follow suit … I don’t want to talk about a climate bill, I’m not doing any more of that.”

Golden is represenative of a smattering of Democrats representing districts that are either toss ups or lean Republican. It may be that GOP efforts to frame the energy transition in culture war terms, as “woke capitalism,” are resonating with voters in Golden’s district.

So, how might the parties’ respective energy platforms matter in the congressional election?

Generally speaking, when pollsters ask voters about their issue concerns, energy and environmental issues rank low on voters’ priority lists. But they may drive votes for certain voters, or as part of a bundle of concerns for many voters. On the other hand, issues seem to be taking more of a back seat to partisan identity in today’s elections. And for congressional elections, partisan identity is all that matters when predicting the outcome of most races, because most districts are dominated numerically by partisans of one party. Consequently, Cook Political Report rated only 22 of 435 House elections as toss-ups, and another 21 as “leaning” in one direction or another. All the rest were either likely (~ 25 seats) or safely (~ 370 seats) in the hands of one party or another.

If only 10 or 15 percent of the House seats are truly competitive, then national energy messaging matters, if at all, in those few competitive races. We can keep an eye on the competitive races where energy issues might matter, either for economic reasons (jobs) or identity reasons (way of life). How might partisan identity interact with energy issues in those places?

The two biggest coal producing states, Wyoming and West Virginia, have become more solidly Republican over time, and none of the toss-up or “lean” districts mentioned above come from those states. Democrats have worried about the loss of support in coal country, and they hope to build loyalty to the energy transition by incentivizing investment in communities have been hurt (or will be hurt) by the energy transition. This was a central philosophical plank of the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act and the 2021 infrastructure bill. But right now, at least, those states are solidly GOP.

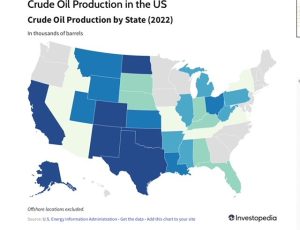

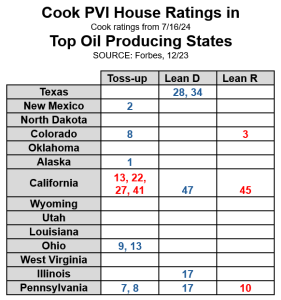

Major oil producing states still contain some competitive House districts, however. The two figures below show the nation’s 32 oil and gas producing states (the map), and the competitive House districts (by district #) in the top oil producing states (the chart). The color of the numbers in the cells indicates which party holds the seat now, heading into the 2024 election (blue for Democrat, red for Republican).

Note that 10 of the districts listed in the chart are from California and Pennsylvania. If we take a closer look at those districts, perhaps we can speculate about how energy policy might matter to voters there.

First, a few caveats. Just because oil is produced in a state doesn’t mean energy issues matter much to voters in these districts. Like wind farms and solar farms, oil wells don’t employ many locals after the construction stage. And if oil production is present, some voters may want it there and others may not. But these districts are nevertheless interesting to watch. In California there is relatively little new drilling, even in oil producing regions. In Pennsylvania, there is new drilling (and hydraulic fracturing) in the Marcellus Shale region.

California

At first glance, if we think of California as a progressive state, the 5 competitive districts in California that are currently represented by Republicans look like pickup opportunities for Democrats. Only two of them (CA-13 and CA-22) are located in the San Joaquin Valley, where most of the state’s oil and gas production is located. Most of the others are in or near Los Angeles. And with the exception of the Palm Springs area (CA-41), all of these districts lean very slightly Democrat. They are listed as toss-ups because of factors specific to this election year.

The San Joaquin Valley districts, where oil is produced, also contain renewables projects. One of them, CA-22, is a truly all-of-the-above energy district, containing oil and gas production, hydroelectric resources, and massive renewable energy capacity. How these Republican incumbents manage their national party’s energy messaging (embracing it, or distancing themselves from it) when campaigning this fall will offer clues about how voters in those districts feel about the energy transition.

The agriculture industry is also strong within both SJV districts, and rural communities have been trending Republican for a long time. Cook lists these districts as D+4 and D+5, respectively, meaning that Democrats have a built in edge, all else equal. Not coincidentally, both are represented by Republicans who sit ideologically to the left of their party’s median member.**

The 2024 Democratic Party platform calls for the agricultural sector to achieve net zero carbon emissions by 2050. It also touts government subsidies to enable that transition as an economic opportunity for farmers. Whether that framing resonates with rural voters remains to be seen.

The Los Angeles districts contain very little energy production, but do host some of the state’s oil refineries. If locals are unhappy with the presence of energy infrastructure in their neighborhoods, perhaps strong energy transition messaging will help the Democrat incumbents, at the margins.

Presumably, if energy messaging influences electoral outcomes in any of these California districts it will be at the margins. But small margins sometimes matter. So we will check in after the election to see whether energy seemed to matter in these races.

Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania, like New Mexico and Colorado, is an oil producing state that sometimes elects Democrats to statewide office. The politics of fracking has complicated races in the state for many years, and is apparently complicating both the Senate and presidential races there this year. Donald Trump and J.D. Vance are betting that a pro-fracking, pro-oil and gas production message will resonate enough in Pennsylvania to capture that state’s electoral votes for Republicans.

The Pennsylvania districts are a similarly mixed bag. The 7th and 8th districts contain traditional coal and steel regions like Allentown, Scranton and Wilkes-Barre, a history that is reflected in the name “Carbon County,” which is part of PA-7. But neither district includes the parts of the Marcellus Shale where the most intense oil and gas production occurs. PA-17 is in the western Pennsylvania, and does includes some oil and gas production areas, as well as a controversial new (and massive) Shell petrochemical plant.

All three of these rust belt districts are represented by Democrats whose ideology scores put them to the right of their party’s median. These are the kinds of places where Pennsylvania’s Governor, Democrat Josh Shapiro, has outshone other Democrats in statewide elections. Cook rates PA-07 and PA-08 as R+2 and R+4, respectively, and PA-17 as “even.” PA-17 is the same district formerly represented by Democrat Conor Lamb, who like current Pennsylvania Senator John Fetterman, positioned himself in opposition to the party’s progressive wing on energy issues. One could imagine energy-as-identity affecting some older voters in PA-07 and PA-08, and energy-as-livelihood influencing voters in PA-17.

PA-10 is a bit of an outlier in this group in that despite its competitiveness it is represented by a Republican (Scott Perry) who is much more ideologically conservative than his party’s median member. His district (R+5) is centered in Harrisburg, and the rural surrounding areas of south-central Pennsylvania. It includes no real energy infrastructure to speak of, and Rep. Perry’s conservatism may reflect his belief that rural Pennsylvania communities are moving in his direction ideologically.

So we will check in with these 10 districts after the election and try to get a sense of whether the national parties’ energy messaging played a role in voters’ decisions, and if so, what kind of role. Stay tuned for that. — David Spence

——–

*Of the four instances in U.S. history in which the winning presidential candidate lost the popular vote, two have occurred in this century — George W. Bush’s election in 2000, and Donald Trump’s election in 2016. And since 2010 the GOP has won a higher share of seats in the House of Representatives than its share of the popular vote in every election, thanks in part to gerrymandering and voter sorting.

** As measured by the DW-NOMINATE data set available at voteview.com.