Of all the political communication pathologies worsened by modern media technology, one of the lesser-known is “rage-farming.” It’s an old idea in new clothes.

Their biographers detail the pettiness of the extended feud between Alexander Hamilton and Thomas Jefferson, and how each tried to amplify the other’s missteps for political gain. Indeed, politicians and lobbyists have long understood the political value of pouncing upon and broadcasting the worst of the other side.

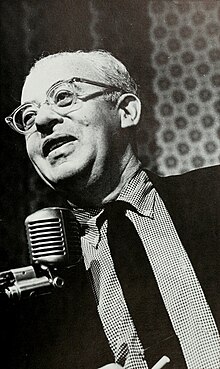

In Climate of Contempt I discuss two 20th century gurus of rage farming-as-political strategy: Roy Cohn on the ideological right, and Saul Alinsky on the ideological left. Both men believed that their respective ends justified their means, and both saw value in provocation. Cohn said “I bring out the worst in my enemies and that’s how I get them to defeat themselves.” Alinsky put it this way: “It’s hard to counterattack ridicule, and it infuriates the opposition, which then reacts to your advantage.”

While the idea of provoking outrage for political benefit is very old, the label — “rage farming” — is very new (coined, apparently, in 2022). Which makes sense. Its recent entry into the lexicon reflects the unprecedented efficiency and power of using the internet to inspire anger among the in-group toward the out-group – instantly, constantly, and at massive scale.

It is perhaps unsurprising, then, that experienced propagandists were among the first to recognize this power. The 2016 election cycle is the first in which experts detected the use of Russian bots and fake social media accounts to try to foment populist alienation on the right and left, though the effectiveness of those efforts is disputed. More recently, Chinese bots and fake accounts have become politically active online in similar ways. This is consistent with longstanding foreign policy strategy in both countries that aims to destabilize adversaries.

In U.S. politics the populist wings of both parties have used rage farming as a successful growth strategy. But according to empirical research, the MAGA wing of the GOP seems to rely far more heavily on manufactured outrage and brazen falsehoods than the populist left does. As I describe in my book, media historians chronicled the ways right wing media embraced a kind of intellectually-sloppy, nastier, provocative style earlier and more proficiently than left wing media did, creating a generation of viewers that carried rage farming to the online world.

For example, the years of the Obama presidency saw attempts to question the president’s citizenship, the tan suit controversy, the “terrorist fist bump outrage,” and the amplification of the “war on Christmas” narrative each December — among many other manufactured stories. These techniques worked; indeed, Donald Trump’s transition to politician was built in part on his promotion of lies about Obama’s birth certificate.

The success of these efforts puts pressure on serious GOP politicians to embrace this angrier populist style in order to win votes. Bobby Jindal, Nikki Haley, and countless others who openly counseled their party against rage farming have subsequently embraced a more populist style in order to preserve their careers within the party.

The MAGA wing of the GOP faces little cost in promoting falsehoods about the 2020 election, the “Biden crime family,” and an ongoing steady stream of conspiracy theories about Democrats. One way to punish the dissemination of misinformation is through defamation litigation, but few of the victims seem inclined to sue, perhaps because public figures must overcome tall hurdles to prevail under U.S. law.

To be sure, some Democrats favor employing a similarly polarizing rhetorical style from the left. Consider for example this “fact check” of Genevieve Guenther’s claims that bioenergy carbon capture and storage will “expose human bodies to DNA-severing electrons.”* It’s not clear how much of the left favors this approach. On the one hand, Guenther has a substantial online following. On the other, recent primary losses by two members of “the squad” may signal the fragility of support for bolder, left-populist rhetoric within the party. But if a second Trump term is as destructive to the regulatory state as its planners promise, might that amplify mirror image demands for more contempt-based rhetoric on the left? Perhaps. Time will tell.

In his speech at the 2024 Democratic Convention, former president Barack Obama urged Democrats not to choose that strategy.

If a parent or grandparent occasionally says something that makes us cringe, we don’t automatically assume they’re bad people,” he said. “We recognize that the world is moving fast — that they need time and maybe a little encouragement to catch up. Our fellow citizens deserve the same grace we hope they’ll extend to us. That’s how we can build a true Democratic majority, one that can get things done.

For now, rage farming seems to be a feature of political debate about climate and the energy transition too. Part 2 of the book contains examples of hyperbolic rage farming to denigrate others who hold different views about particulars of the energy transition.

In July former FERC Commissioner Neil Chaterjee posted a puzzling tweet that said “For the sake of my daughter I hope Dems run Biden” because a Trump victory would “send a terrible message to young girls” and Biden would be blamed for it. Chaterjee’s responses to those who took issue with the tweet had the hallmarks of a gleeful online rage farmer: “Thanks for giving [my] post oxygen!!!” I found the tweet disappointing* because as FERC Commissioner Chaterjee did not strike me as the MAGA warrior type, and I had labeled him as a non-MAGA conservative because of his connections to Trump enemy Mitch McConnell.

But if he wants a future within the GOP, he has to try to reconcile some very difficult to reconcile (i) the fact that no Republican politician can survive within the national party by challenging the climate of contempt that seems dominant in party messaging, with (ii) an awareness of what a second Trump administration has planned for the dedicated careerists at the FERC with whom he worked — the people who help make our complex energy markets work.

One reaction to that kind of cognitive dissonance is to create narratives that place the blame for the harm done by a Trump presidency on Democrats, as Chaterjee did. It is not that identifying the political missteps of the Biden administration is wrong, or even observing that a second Trump presidency was made more likely by those missteps. But it ought to be self-evident that those who oppose Trump bear no moral responsibility for the consequences of his election, and that those who understand the dangers and support him nevertheless are much more culpable (morally).

Meanwhile, rage farming seems to be here to stay, at least until viewers and voters stop rewarding it by buying what rage farmers are selling. – David Spence

———-

*I tweeted my disappointment in response. But it was an ill-conceived response on my part. It was immediately apparent from the tone of the exchanges between Chaterjee and others that this was not likely to be a productive exchange anway. So I deleted my reply.

**That quote comes from Guenther’s new book on climate politics, which came out about the same time as Climate of Contempt. She has more than 75,000 followers on Twitter/X, and I cite examles of Guenther’s hyperbole in my book — particularly her casual application of the terms “genocide” and “murderer” to those she regards as climate villains.