In Climate of Contempt I argue that, in politics, we are too casual about developing negative judgments of others in the absence of complete information about what drives their choices. This pops up in various ways throughout the book, one of which is the introductory chapter’s admonition that ideas deserve to be evaluated on their own merits irrespective of the faults of those who articulate them.

This is just as true of the foundational ideas of environmentalism as it is of economic ideas. Increasingly, writers have attempted to tarnish both sets of ideas by associating them with their expositors’ moral failings. Chapter 2 and Appendix C of my book provide examples of this in the context of public choice economics; this post focuses on environmentalism.

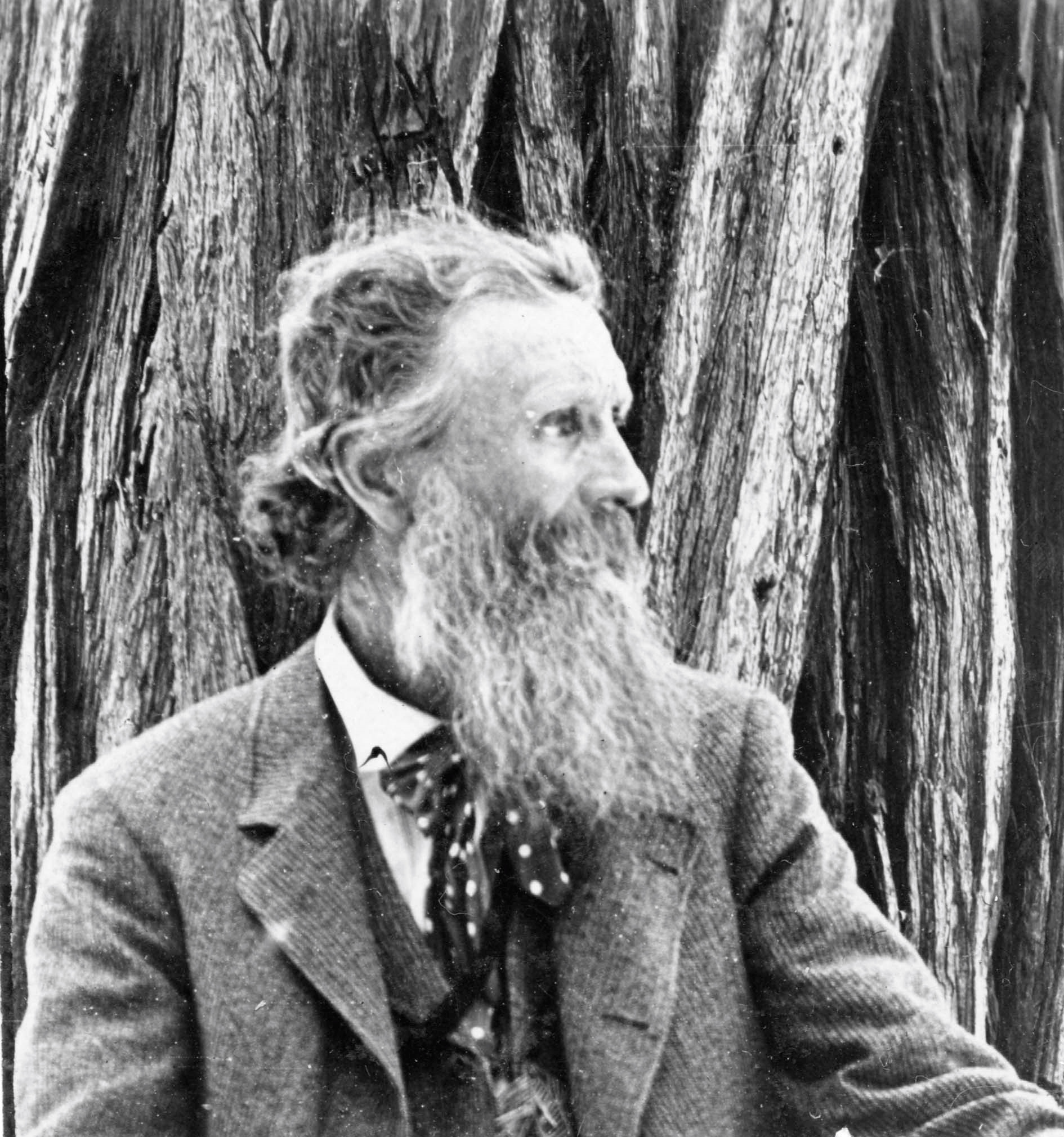

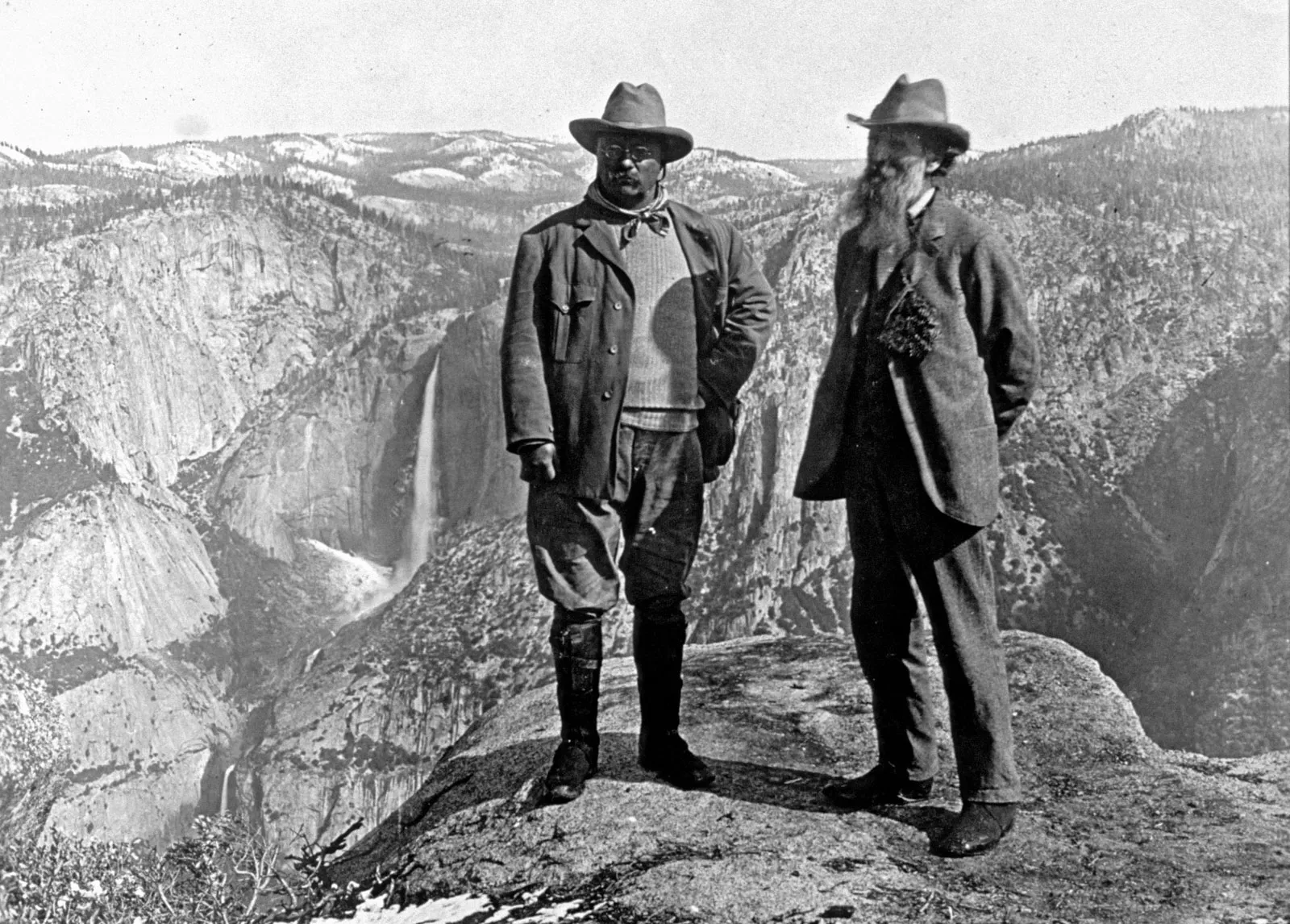

If anyone is the father of American environmentalism – at least its preservationist branch – it is John Muir. Muir was the driving force behind the creation of Yosemite National Park and development of the U.S. national park system. His love of wild places, his prolific writings on the value of preserving those places, and his founding of the Sierra Club place him firmly on the Mt. Rushmore of environmentalism.

Muir came to Wisconsin from Scotland at age 11 with his family in the 1870s. In his young adulthood he lived in Indiana, explored Canada, and once walked from southern Indiana to Florida – all before making his way to California, where he lived for most of his life.

At least three different places claim to have exerted the formative influence over John Muir’s environmentalism: (1) California’s Yosemite Valley, (2) Florida’s Gulf Coast, and (3) Muir’s childhood home in East Lothian, Scotland.[1] We see the vestiges of these claims in the John Muir Trail in California’s Sierras, the Muir Ecological Park in Yulee, Florida, and the John Muir Way in Scotland. I have never been to the first two, but I was fortunate to walk a portion of the John Muir Way earlier this summer.

The 134-mile long John Muir Way crosses the whole of Scotland from west-to-east, and ends (or begins, depending on which direction you are walking) in Muir’s hometown of Dunbar. It is a beautiful walk, as I am sure are the other trails that bear the Muir name.

The Muir birthplace and museum in Dunbar includes an exhibit that explains Muir’s ideas on human ecology – sometimes described as his “biocentrism.” But the exhibit is precise. It is true that Muir did not want wild places spoiled by logging, mining or other ecological and aesthetic disturbances. He thought wild places should be preserved, but he wanted them preserved for people to enjoy. For Muir places like Yosemite and Yellowstone and East Lothian and the Gulf Coast were sacred places in which humans could commune with (and see evidence of) God, and enjoy a kinder sort of spirituality than the cruel, spartan life forced on him by his father’s version of Christian fundamentalism.

Muir’s prolific writings made these ideas enormously influential, even foundational to the first environmental movement in the U.S. More recently, however, Muir’s legacy has been reevaluated according to modern sensibilities governing language and treatment of historically persecuted subgroups of U.S. society.

In 2020, in an article entitled “Pulling Down Our Monuments,” the Sierra Club’s Michael Brune took Muir to task for “derogatory comments about black and indigenous people,” a charge Brune supported by linking a 2016 article about Muir by Justin Nobel. Nobel’s article is long and delves into Muir’s expressed disdain (in some of his writings) for technologically backward people of all ethnicities (calling them “savages”), and it notes the irony of lionizing Muir for walking distances through unspoiled country in ways that native Americans had done for many centuries. Either ignorant of or indifferent to the repression of indigenous tribes and black people, Muir denigrated wigwams as the dwellings of savages, and inferred from the unsanitary and dirt poor conditions in which black people lived in the 19th century south that those people were backwards or uncivilized.

Brune’s essay is here. It is about more than Muir. It is partly a mea culpa for the role of racists in Sierra Club’s history, one that condemns Muir mostly in support of that mea culpa. Indeed, part of Brune’s indictment of Muir is based Muir’s association with racists and eugenicists (as opposed to ascribing those views to Muir himself).

Nobel’s article is here. It dives more deeply into Muir’s life and attitudes. Nobel is not hesitant to apply today’s ethical norms to the language and writing of a 19th century transplanted Scot. But there is also some understanding and sympathy in the essay’s title (“The Miseducation of John Muir”) and in the fullness of the context that Nobel provides.

Brune’s essay provoked a powerful reaction within the Sierra Club. One can find a chronology of that reaction with links to all of the relevant documents here. Most Muir biographers believe that Muir’s attitudes grew more tolerant as he matured, a fact acknowledged in the Nobel essay (but not the Brune essay). Like Eleanor Roosevelt’s youthful-but-casual anti-semitism, Muir’s intolerance and disdain for the lifestyles of persecuted peoples apparently faded away with age. Nobel put it this way:

It is also true that Muir’s views did change over time. He was 29 on his walk to the Gulf, and not much older when he first entered California. Later in his life, he traveled to Alaska. Muir lived among various tribes, including the Chukchis and Thlinkit. “He grew to respect and honor their beliefs, actions, and life styles,” wrote scholar Richard Fleck, in a 1978 article in the journal, American Indian Quarterly. “He, too, would evolve and change from his somewhat ambivalent stance toward various Indian cultures to a positive admiration.

To their credit, the Sierra Club has not erased Muir from the club record. It still maintains on its web site something called the “John Muir Exhibit,” albeit with the proviso that “its contents do not necessarily represent the viewpoint of the Sierra Club.”

The human brain sometimes struggles with moral ambiguity. We seem to want to reach “thumbs up” or “thumbs down” conclusions about people. This is doubly true in the heat of battle, and triply (if that’s a word) true in the internet age, when we are constantly invited to hold others in contempt based on a single fact or event.

But people are complicated. They do good things and bad things. They change over time. We ought not to use their foibles to influence our sense of the value of their ideas. We will understand the politics of the energy transition better if we approach its discussion with more curiosity and lessl judgment. – David Spence

—————-

[1] Most Americans associate Muir’s environmental philosophy with his love of Yosemite. See e.g., Robert Engberg’s John Muir: To Yosemite and Beyond. But Jack Davis’ The Gulf: The Making of an American Sea credits Muir’s Florida experiences with “convincing [him] that positioning humans above nature was one of Western society’s greatest conceits.” (p. 244). And unsurprisingly, the UK’s John Muir Trust and Muir’s homestead and museum in his bucolic hometown of Dunbar, Scotland claim the honor of inspiring Muir’s philosophy.