[This is post number 3 in a series of posts reviewing new books addressing what we know, and don’t know, about today’s politics. The first two posts are here and here, respectively.]

The Next Two Books: Understanding Angry Voters

Yesterday’s books focused on rural communities and their ambivalence about climate regulation and the energy transition. These next two books help us understand the voters who dominate primary elections in the form of authoritative, concise, and readable explanations of the the growth of bitter partisanship. These books help us understand why Congress is incapable of translating majority preferences about climate politics into policy — even though neither book is about climate politics per se. The books are:

- John H Aldrich, Suhyen Bae, and Bailey K Sanders, The Fundamental Voter: American Electoral Democracy, 1952–2020 (Oxford U Press, 2024).

- James N. Druckman, Samara Klar, Yanna Krupnikov, Matthew Lewendusky, and John Barry Ryan, Partisan Hostility and American Democracy: Explaining Political Divisions and Why They Matter (University of Chicago Press, 2024).

The Analyses

Written by three political scientists,[1] The Fundamental Voter updates a classic political science text on voting behavior — Campbell, Converse, Miller & Stokes’ The American Voter (1960). That earlier book concluded that the only omnipresent, long-run driver of voting behavior — the only voting “fundamental” — was party afffiliation. Yes, short-term, candidate- or election-specific factors might exert strong short-term or election-specific effects on voting behavior, said Campbell et al., but those effects were too ephemeral to be considered “fundamental.” In The Fundamental Voter, Aldrich et al. use data from the University of Michigan’s National Election Study (NES) to show that there are now four additional long-term drivers of voting behavior, making a total of five fundamentals: party affiliation, ideology, (certain recurring) issues, race, and the economy.[2]

These additional fundamentals began to appear in the 1960s and 70s, signifying that voting had become, in the authors’ words, “infused with a greater amount and variety of substantive politics.”[3] That is, the electorate became more ideologically- and policy-aware during these years, say the authors, and that awareness produced durable views about ideology (including the relationship of regulation and markets), race, the economy and a few other recurring issues.[4] Crucially, after the 1984 election[5] these four newer fundamentals began to sort along party lines, a trend that continues today. This sorting is exacerbating the polarization and negative partisanship I describe in Climate of Contempt.

Because the newer fundamentals now all “point in the same direction,” say Aldrich et al., fewer and fewer voters hold combinations of beliefs that favor some ideas that Republicans champion, and others that Democrats champion. As a consequence, split ticket voting has decreased sharply, party loyalties have hardened, and victory by the other side has come to seem catastrophic because it will defeat all of voters’ fundamentals-based hopes at the same time. The Fundamental Voter credits this dynamic with exacerbating negative partisanship, noting that the latter problem is growing within both parties. (This “both sides” idea offends the sensibilities of some,[6] but the NES data[7] make the point essentially inarguable.) The Fundamental Voter stops short of crediting the changing media environment for the evolution of the fundamentals in the 21st century, though it does discuss some of the authors who point to media forces as drivers of partisan bitterness.[8]

In some ways Partisan Hostility and American Democracy picks up where The Fundamental Voter leaves off, diving more deeply into the causes of negative partisanship (as distinguished from partisan polarization). The authors, Druckman et al., are political scientists and media/communications scholars who see growing partisan animosity as partly the product of ideological sorting, but credit other contributors as well, including modern media.

This book uses a recent, multi-year panel survey to examine how partisan animus interacts with other variables to drive oppositional behavior among partisans, influencing voters’ beliefs and attitudes toward candidates and issues in new and troubling ways, and further strengthening centrifugal forces in our politics.

We find broad-ranging effects of animosity on policy positions, responses to the COVID-19 pandemic, evaluations of public figures, support for political compromise, and support for undemocratic practices … In each of these cases, animosity polarizes individuals: as animosity increases, so does the partisan gap in issue positions … [H]igher animosity correlates with larger gaps in opinions.

…[High-animosity partisans] are more ideologically extreme and sorted, and they also discuss politics and post about politics on social media more frequently than those with lower animus. … [C]itizens assume that the images they see on mass media and on social media reflect reality, and thus that the other party consists of extremists … [They] perceive the other party in ways that could be problematic to pluralism…[9]

This last point tracks my analysis in Climate of Contempt, which is unsurprising since I cite some of these same authors there.[10]

Druckman et al. present an experiment showing that when we attach a party label to an issue, high-animus partisans change their views about the issue and its importance. In the authors’ words, “everyone likes compromise, but when it is clear which party will be doing the compromising, animus matters. For high-animus respondents compromise means the other side makes the concessions.”[11] Party elites have the power to attach that party label to otherwise bipartisan or nonpartisan proposals. Indeed, Donald Trump demonstrated as much when he “killed” a bipartisan immigration reform bill in late 2024. Trump’s intervention turned Republican champions of the bill into opponents almost instantly, simply by defining the GOP position in the eyes of voters who GOP members of Congress could not afford to anger.

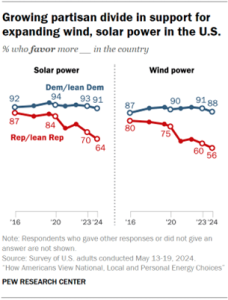

This is a worrying state of affairs not only for democracy, but also for the energy transition. Donald Trump dislikes renewable energy. GOP party elites have been turning more strongly against the energy transition and climate policy since the first Trump Administration. But that turn did not begin to appear in rank-and-file opinion until the Biden years. And the second Trump Administration’s more aggressive attack on renewable energy and climate science is likely to accelerate it.

How Problematic for Democracy?

Both of these books note (as others have) the similarity between today’s partisanship and the sorts of intense, durable “factions” about which the nation’s founders worried. Aldrich et al. see danger to democracy in the sorting of fundamentals along party lines because it makes losing seem too consequential. They see parallels to the antebellum era, and liken the sorted fundamentals of today to the kind of broad, deep political cleavage that slavery produced in the pre-Civil War United States. (And of course they see race as a key component of division in both eras.) That earlier cleavage ultimately broke the republic.

For their part, Druckman et al. are a bit more sanguine. They see danger in the outsized influence of especially “hateful partisans” (their term). And they worry about the speed and effectiveness with which today’s party elites can transform voter animosity into new beliefs and positions. But at the same time, they see room for hope in the fact that the high-visibility partisans who toxify public debate (and politicians’ behavior) are not representative of the electorate as a whole. They express doubt that that animosity will necessarily feed a “doom loop” of ever-more hatred and disagreement, because most of the electorate is less ideologically extreme, less politically engaged, and displays less animosity than active partisans do.

Furthermore, Druckman et al.’s results suggest that propaganda gets less effective when voters’ personal stakes — the consequences of being wrong — are high enough. In those situations, say the authors, people work harder to find out the truth. They show that this was true of vaccine skeptics whose unvaccinated loved ones died of COVID. Perhaps, therefore, as more people experience the high costs of climate change they will abandon partisanship as a guide to their voting behavior.

Still, both books stop short of declaring that “the truth” will win out in the end. They instead seem to suggest that there is hope that it will. In that respect their approach feels similar to my own. The high-animus, always-on-line warriors may be a lost cause, but others should be more moveable. These are the people who I call the “persuadables” in chapter 6 of my book. Perhaps they will pull American democracy back from the brink in the end.

Conclusion

Of the five books I am reviewing in this series, these two — The Fundamental Voter and Partisan Hostility in American Democracy — best reflect the circumspect ways in which political scientists discuss the workings of political process. These two books will do the most to inform lay readers’ understanding of today’s climate and energy politics. Again, that may sound odd since neither book focuses on climate and energy, but they focus on something more important: why voters have chosen as they have. In my opinion, these are the kind of data-driven analyses that climate policy scholars, pundits and reporters ought to read, engage and respect.

——————–

[1] Full disclosure: The lead author of the book, John Aldrich, was my Ph.D advisor at Duke. I cite him in my book, am a great admirer of his work, and consider him a friend.

[2] These five fundamentals are of course overlapping categories and Aldrich et al. offer appendices in the book and online to explain how they identified them as distinct and fundamental drivers of votes.

[3] The Fundamental Voter, p. 113.

[4] The five recurring issues the authors identify as (one combined) “fundamental” are attitudes toward (i) government health care, (ii) government responsibility for ensuring good living standards, (iii) defense spending, (iv) the size of the welfare state, and (v) government services aimed at minority groups.

[5] “Beginning in or around 1984, presidential contests became increasingly close races between the two parties and any influence of the candidates, even of incumbents, which once loomed so large, has on net receded.” The Fundamental Voter, p. 4.

[6] Climate of Contempt, Appendix G, pp. G-7 through G-9.

[7] Climate of Contempt, pp. 118-19.

[8] The Fundamental Voter, pp. 125-137.

[9] Partisan Hostility in American Democracy, pp. 3-5, and 170 (emphasis added). Here the authors cite much of the same social scientific literature I discuss in Climate of Contempt.

[10] I speculate that as the propaganda machine ramps up negative partisanship, “party affiliation may now be driving issue preferences, not the other way around.” Climate of Contempt, p. 122.

[11] Partisan Hostility in American Democracy, p. 136.

[10] See especially Part II.

.