A Texas faculty friend who worries about our political descent keeps asking me “So, how does it end?” He shares my sense that today’s assault on our liberal democratic institutions is more than a swing of the pendulum to the political right. It looks more like an historical pivot toward a more authoritarian form of government. I tell him that I don’t know how it ends. But as with climate change, if we want to avoid its worst effects it pays to take a clear-eyed look at what is actually happening, and to avoid being distracted by misleading narratives that just confirm our prior beliefs.

Those of us who write about climate and energy policy have no choice but to think about politics, because politics determines the viability of potential solutions to national policy problems. As our policy-making institutions crumble under the weight of ideological polarization and negative partisanship, the menu of viable solutions shrinks. Some of us ignore the difficult political environment and write for an assumed or imagined future in which “the pendulum swings back” to a more functional policymaking process But for others of us, the awareness of the political breakdown colors both our policy diagnoses and our policy prescriptions. We either tailor our work to the narrowing set of “realistic” options, or incorporate proposed “fixes” to the dysfunctional system itself. Politics necessarily creeps into our work.

Non-experts, in turn, rely on journalists, academics, and pundits to understand policy problems and solutions. That imposes a duty on experts to be conscientious about getting the facts right. Most experts are conscientious in that way, but less so when it comes to politics. They defer to scientists on matters of climate science, or to economists on economic matters, for example, but not to political scientists when it comes to politics.

Why? Sometimes the cause is “I’m smarter than they are” hubris. There are academic economists who like to treat politics and political behavior as “just another market.” In his 2014 address as president of the American Finance Association, Luigi Zingales reasoned through the politics of finance in just such a manner (“Rich financiers can easily buy their political protection …”), ignoring great swaths of empirical work that contradicted his conclusions.

Other pundits and academics may think they know better simply because they have had to form beliefs about government and how it works in order to decide how to cast their vote. That sort of intuition is good enough for voters, who claim no particular expertise on the subject. But it is not good enough for experts who write about policy issues, and on whom readers and listeners rely. Their beliefs about power and political economy ought not to be so tightly held that they can’t be exposed to what empirical political science has to say. Indeed, expertise is supposed to be the product of just that kind of exposure.

So, pundits, writers, and academics have three defensible choices: (1) be cautious, precise and circumspect when opining about power and politics, (2) refrain from opining on those topics at all, or (3) get familiar with what empirical social sciences have to say about them. Option number 3 is best. Political scientists study our political institutions more closely than others do, and they measure. They have created a body of knowledge that deepens our understandng of regulatory and climate politics. We all ought to use it.

My book explains what I think empirical political science tells us about today’s regulatory politics, which is that the most rigorous empirical work (a) suggests circumspection about the ability of corporations to use money to control the policy process for their own ends, and (b) points toward a more voter- and media-centric dynamic that is amplifying the voices of the most ideologically extreme and negatively partisan voters.[1]

If I have gotten some of that wrong, my understanding will benefit if others point that out — not by simply saying so, or with an anecdote or two, but by bringing rigorous evidence to the discussion. I am not suggesting that everyone can be like the late David Broder, who prowled the halls of the annual meeting of the American Political Science Association, collecting papers as a check his own understanding of how American politics works. But when experts ignore what we know from empirical political science in favor of a cherished narrative, they aren’t doing their job.

So …

In the spirit of actively open-minded thinking and checking my own understanding against new information, over the next three days I will review five new politics books.[2] All five aim to illuminate our understanding of today’s climate or regulatory politics, directly or indirectly, and all are from academic presses. Three were written or co-written by political scientists, and two were not: but the two put empirical claims about politics at the center of their analyses.

Collectively, the five books challenge parts of my analysis in Climate of Contempt, while confirming other parts. And they illustrate the error of pat generalizations about the many and complex sources of our current political dysfunction, and why those pat generalizations are common nevertheless.

So here is the plan of attack:

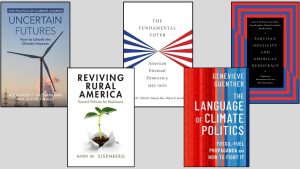

Tomorrow (5/2), we look at two books that explore rural communities’ ambivalence to the energy transition: Alexander F. Gazmararian & Dustin Tingley, Uncertain Futures: How to Unlock the Climate Impasse (Cambridge U Press, 2023); and Ann M. Eisenberg, Reviving Rural America: Toward Policies for Resilience (Cambridge U Press, 2024).

The next day (5/3), we examine two empirical studies of partisan polarization and partisan animosity, and what they have to say about the origins of these phenomena: John H Aldrich, Suhyen Bae, and Bailey K Sanders, The Fundamental Voter: American Electoral Democracy, 1952–2020 (Oxford U Press, 2024); and James N. Druckman, Samara Klar, Yanna Krupnikov, Matthew Lewendusky, and John Barry Ryan, Partisan Hostility and American Democracy: Explaining Political Divisions and Why They Matter (University of Chicago Press, 2024).

On 5/4 we turn to politics in the public square, and compare the way political scientists discuss politics to the way pundits and active partisans do — by way of my review of Genevieve Guenther’s, The Language of Climate Politics: Fossil Fuel Propaganda and How to Fight It (Oxford U. Press, 2024).

I hope you find these reviews helpful. But most of all, I hope that they inject more precision and circumspection in the way we talk about climate politics online. — David Spence.

———————————–

[1] Because my job is to help people understand climate politics (not push them toward particular policy views), I cite political scientists who disagree with me, and then explain why I tend to credit some empirical research over other research.

[2] Four of these books were too recent to have been included in Climate of Contempt; one came out just before my book went to press and I did not see it in time to reference it in my book.