The national GOP has taken a fairly sharp turn against green energy in the last few years, suggesting that persuading GOP politicians to support a lower-carbon energy future is unlikely in the near term. Instead, it looks like the only near term path to stronger climate policy is more Democratic Party victories in future elections. But while Democrats in Congress are united in support of the energy transition, they remain divided in other ways. And they disagree about the most likely route to future electoral successes.

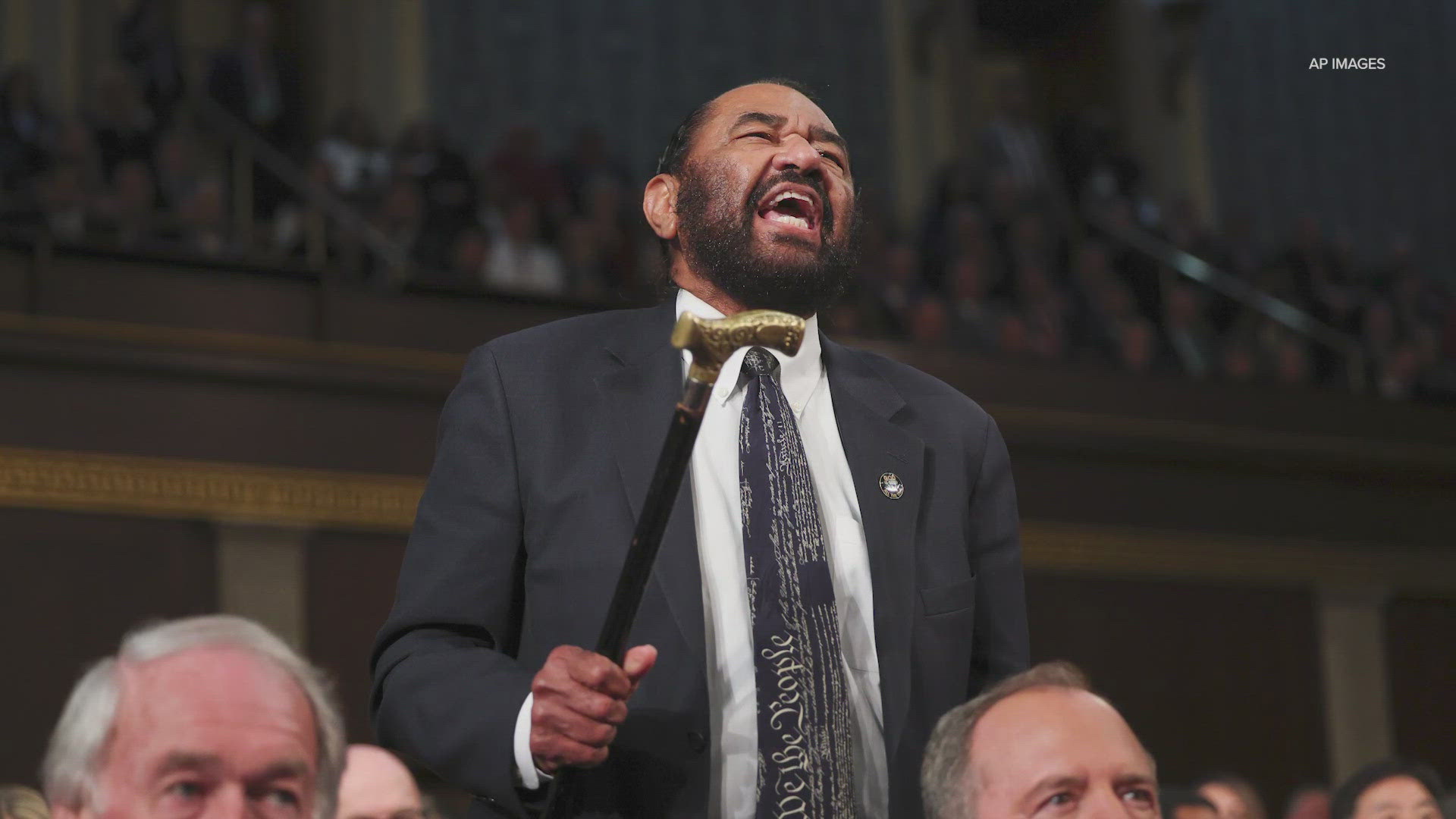

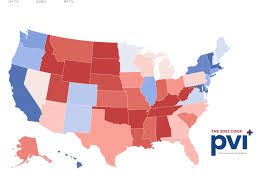

A few weeks ago three items came across my news feed on the same day that illustrate this problem. One was a report on the censure of Rep. Al Green for his organized protests during President Trump’s March 3 address to Congress. The second was an article in The Atlantic describing Rep. Elise Slotkin’s approach to delivering the democratic response to that address. The third item was about the Cook Political Report’s publication of historical PVI ratings for all 50 states from 1997-2024.

Let’s take The Atlantic piece first.

The article, by Tim Alberta, is an account of how Slotkin approached the task of delivering the opposition’s remarks from the time Senate Minority Leader Charles Schumer asked her to do so until she delivered the speech on March 3d. But it is also an account of Slotkin’s enthusiastic rejection of progressive “identitarian” politics, and her focus on economic issues instead. Alberta:

Slotkin argues that the surest way to heal the country—to defuse identitarian struggles, pacify the culture wars, uncoil our hypertense politics—is by restoring the confidence of working families. When people feel assured of their financial welfare and of their children’s future, she insists, they become far less receptive to the type of strongman demagoguery that thrives on scapegoats and feasts on anxiety.

This approach sets Slotkin apart from many of her fellow Democrats, though the difference is better measured by degree than kind. She is quite familiar—as a woman, as a Jew, as the daughter of a woman who came out late in life as a lesbian—with the plight of certain constituencies within her party’s coalition. It’s simply a matter of emphasis: Slotkin sees electoral success as the path to addressing America’s injustices, not the other way around.

To my mind, Slotkin’s optimism about returning economic issues their dominant position in the minds of voters may be underestimating the power of the propaganda machine to elevate cultural divides in voters’ minds. Nevertheless, Alberta goes on to note correctly that Slotkins’ approach was unpopular with a segment of progressives:

Naturally, not everyone was thrilled with what they heard. “Slotkin’s address suffered from the same half-heartedness that has seized the Democrats since last November,” my colleague Tom Nichols wrote in The Atlantic, echoing some of the criticism online. “Her response, and the behavior of the Democrats in general, showed that they still fear being a full-throated opposition party, because they believe that they will alienate voters who will somehow be offended at them for taking a stand against Trump’s schemes.”

This is the view that “fighting back” implies a “full-throated” intensity of feeling – the same hostility, the same contempt – that the captive-of-MAGA GOP now regularly displays toward Democrats. In this framing, fighting back is as much about tone and emotional style as it is about substance. Nor is tone the only cleavage line in the party divides. Aspects of Slotkin’s background disqualified her in the eyes of influential progressive Twitter accounts, who criticized the party’s decision to have a “former CIA operative and hardcore Zionist” and “national security Karen” deliver such a “contemptible response” to Trump.

Of course, many Democrats disagreed with these assessments. (Slotkin’s remarks were short (10 minutes), and you can judge for yourself by watching them here.) But Alberta is probably correct when he describes Slotkin’s philosophy as one that “wins” in places where Democrats need to win. The article explains why Slotkin “reject[ed] all of the suggestions she received about her speech. … The problem isn’t with any of the[] particular causes [she was asked to champion], she said; the problem is that everyone seemed focused more on the people she might name in her remarks and less on the people who would be at home listening to them.”

Which brings us to what the Cook PVI data tell us.

Readers of this blog or of Climate of Contempt can anticipate the story the new Cook data tell: namely, that the electoral strategies Slotkin rejected are unlikely to help Democrats win control of national policymaking institutions in the near term. Those strategies do have a logic. They are intended to move the Overton Window: i.e., to change public opinion in the long run. But in today’s information environment they are more likely to be weaponized effectively against Democrats than to help Democrats win elections in the few remaining contestable jurisdictions.

David Wasserman’s summary of the data (subscription required) hits the key points:

As recently as 2005, the states of West Virginia, Arkansas, Ohio, Missouri and Iowa performed within a few points of the nation as a whole. Today, obviously, they’ve exited stage right. The same was true back then of Oregon, Washington and Colorado, which have exited stage left. …

Just two generations ago, America was hardly geographically polarized at all at the presidential level. In the 1960 race between John F. Kennedy and Richard Nixon, there were 34 states decided by single digits and 20 states decided by fewer than five points. Fast forward to the 2024 race between Trump and Kamala Harris, and just 13 states were decided by single digits, and just eight states were decided by fewer than five points [Cook’s definition of “competitive”].

This is the same story we see in congressional elections. Crucially, the decline in competitiveness favors the GOP in presidential elections. Wasserman again:

Today, going by Cook PVI, there are 31 states totaling 312 Electoral College votes that are more GOP-leaning than the nation as a whole …. In other words, Trump performed better in these 31 states than he did in the national popular vote. …

Back in 2013, just 27 states totaling 255 Electoral votes were more GOP-leaning than the nation as a whole (23 states plus DC totaling 283 votes leaned Democratic). And in 1997, 28 states totaling 271 Electoral votes were more GOP-leaning than the nation, while 22 states plus DC totaling 267 votes leaned Democratic — virtually no skew at all.

In other words, the key to the policy future lies in the hands of small group of people in swing jurisdictions, many of whom currently vote Republican. Progressive messaging may be working to solidify support in blue states and districts, but doesn’t seem to moving the needle in the desired direction in competitive places. These data suggest that future Democratic presidential nominees may be wise to follow Elise Slotkin’s approach.

Nevertheless, some progressives willing to risk alienating moderate voters in contestable jurisdictions in the hope that it (a) activates more new voters than the voters it alienates, and (b) nudges the Overton Window in the “right” direction. They may see no downside taking this chance. It may also be that they see no important differences between Democratic Party moderates who represent contestable jurisdictions now, on the one hand, and Republicans on the other. They may view both groups as corrupted by corporate interests, despite the fact that measures of ideology put moderate Democrats much closer to progressives than to even the most moderate Republican.

Last, consider the House vote censoring Rep. Al Green.

For those who missed the Al Green controversy, Rep. Green stood early in the president’s speech and heckled the president for a few minutes, and was eventually removed from the chamber. Two days later the House censured Green, 224-198. Tired of being alone during his chamber protest, Green successfully enlisted several of his co-partisans to oppose censure a few days later by singing the protest song “We Shall Overcome.” But in the ensuing vote Green was unable to convince House Democrats to stay together, as 10 of voted in favor of the censure.

The 10 House Democrats who supported the censure represented different types of districts from a variety of states. We don’t know why they voted the way they did; collectively, however, their districts’ Cook PVI scores average D+2.3, much more competitive than the House average. Some of the 10 may be people who feel as though they are in a bit of an electoral bind. They understand that the forces pushing politicians to the ideological extremes affect their party too. They must try to please both primary voters, who are more ideologically extreme and negatively partisan than the average party member. But the things that help elected Democrats enhance their chances of winning a primary election may hurt their chances of winning the general election in a contestable seat, and vice versa.

In competitive seats, signalling moderation and bipartisanship may make electoral sense.

Back to the Energy Transition

The second Trump Administration is making it clearer than ever that climate policy and the energy transition are partisan issues. This is not a surprise, given that the last decade has seen the departure of the most prominent climate hawks from the GOP congressional caucus. And Republican politicians who claim to value stronger climate policy rarely back up those claims with their votes. Indeed, the forthcoming votes over the repeal of the Inflation Reduction Act will show us more about those putatively pro-climate conservatives, and exactly how hard the congressional GOP will work to derail the energy transition.

Meanwhile, if stronger national climate policy requires Democratic Party victories, that, in turn, implies winning elections in places where Republicans win them now. Some Democrats have done well in those kinds of places. Perhaps the party’s national message-makers ought to listen to those people. – David Spence