I have learned that there is one sentence in Climate of Contempt that, more than any other, seems to grate on the the ears of some in the climate coalition. It is found on page 166:

“[O]ur economy’s deep reliance on petroleum products is due less to that industry’s long tradition of throwing its political weight around than to the attributes of its products.”

As explained in the book, this claim is not about the impossibility or unworthiness of the energy transition project, but rather about understanding it fully.

But, that sort of clear-eyed look at the task does underscore the importance of the “net” part of aiming for a net zero carbon economy. Some oppose developing a carbon sequestration (CS) industry for fear that it will slow the search for fossil fuel substitutes, or because they oppose a continuing role for the fossil fuel companies likely to be active in CS sector. But viable negative emissions technologies (NETs) and CS will be essential to the transition.

One way to make your own assessment of the truth of my claim (about why petroleum products are so ubiquitous) is to spend a few hours rigorously investigating the role of petroleum products in your own life, and why we use them. Ignore the obvious things like fossil fuel powered transportation, or fuels for cooking and heating. The process of transitioning to lower carbon in those sectors is relatively advanced because alternative options exist. Look instead at the objects you use every day, what they are made of — and especially why they use petroleum derivatives.

For example, we all wear clothes, use home appliances, and enjoy hobbies. About 60 percent of all clothing is made with synthetic fibers. This is so despite the facts that natural fibers predate synthetics, and synthetic fiber made from the petroleum molecule shed micro plastics that enter the food chain and otherwise contribute to plastic pollution.[1] Why? Synthetics are prevalent because they offer comparable attributes at lower cost, and are often more durable, thereby allowing more of the world’s consumers to enjoy those attributes. Replacing synthetic fiber with natural fibers is technologically straightforward, but would displace land used for other purposes and price some consumers of warm, durable clothing out of the market (in the absence of redistributive policies to remedy the problem).

Next, consider appliances. Irrespective of the energy sources that power them, our refrigerators, stoves, coffee makers, vacuum cleaners, laptops, phones, and other appliances are almost invariably made of metals or plastics. The production of stainless steel, cast iron and hard plastics emit carbon and other pollutants. We use them because they offer attributes consumers want at the most affordable price. That price omits the social costs of pollution. Again, plastics can be made from vegetable oils, and greener steel production is becoming technologically possible. But that transition will include a period in which substitutes are more expensive for consumers. And while a world in which all light- and heavy-duty vehicles, refrigerators, stoves, and other steel products use the lowest emission production methods is not a zero emission world, it could be a net zero one.

Finally, what are your hobbies? Maybe they involve playing music or sports. I have two guitars at home, one electric and one acoustic. Both are made mostly of wood. But their tuners, strings, bindings, fingerboard inlays, and electronics use various metals and plastics. The mineral oils or shellac used to finish the woods are also petroleum-based. What natural products would you substitute for these petroleum-based substances?

The same can be asked of sporting equipment. For example, tennis rackets use graphite, carbon fiber, and nylon strings that are derived from petroleum. Golf, basketball, football, hockey and most other popular sports depend (for now, at least) on petroleum products. So does outdoor recreation. Tents use nylon and lightweight steel or plastic. Canoes are made from specialty materials like ABS or Kevlar, or aluminum. The production of all of these substances emits carbon. We can return to canvas tents, wooden canoes, and balls made of animal leather, but that seems unlikely. New non-petroleum based substitutes of equal quality are likely to emerge, but will be expensive in the medium term.

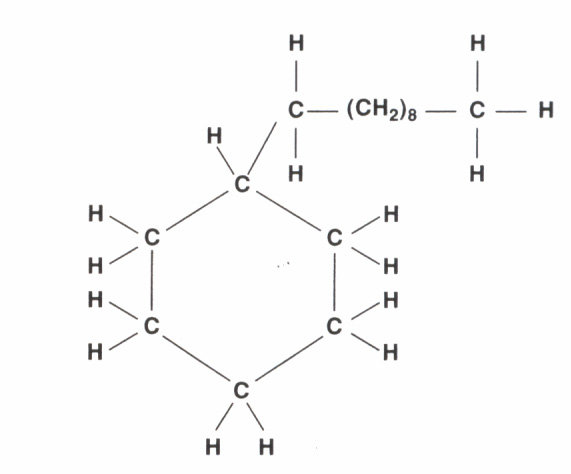

The list goes on and on. Virtually everywhere you look in your home and on your person you were find products that are most affordably and durably made using a petroleum molecule because consumers have chosen those products, based upon their prices and attributes. (And one could fill another blog post summarizing the role of plastics in the advancement of medical care.)

Which is not to forget that today’s choices were facilitated by prices that were artificially low; they did not account for the carbon and other pollution that were part of the production process. That is part of the reason why many of us now seek a transition toward a lower or net zero carbon economy. But that is a much more difficult task than some seem to appreciate, and it involves trade-offs that (if not made wisely) could harm the most economically vulnerable among us. In any case, those tradeoffs have to be made collectively.

Concerns about consumer prices may be why John Podesta touted the boom in oil and gas production during the Biden Administration as a “victory.” Or why those responsible for ensuring a reliable electric grid worry about having enough natural gas-fired generation on the grid. They are not enemies of the transition; they are people responsible for meeting a different public goal: namely, ensuring a reliable energy supply.

All of which implies — to many of us, at least — the need to develop the NET and CS industries. As with renewable energy, electric vehicles, and other fossil fuel substitutes, these industries will not scale up instantly. There will be fits and starts and setbacks along the way. These are a necessary part of the journey to commercial viability, which is why Congress has chosen to incentivize the development of CS and NETs.

Not long ago former Secretary of State John Kerry challenged the CCS industry to prove it could be a part of the transition. At the same time the Biden EPA is depending upon that industry’s viability to support the legality of its power plant rule.

It’s a touchy subject within the climate coalition. Some members of he climate coalition lament these all-of-the-above approaches. I think we ought to celebrate them. — David Spence

[1] One can find analyses suggesting that production of clothing from some natural fibers have higher carbon emissions than clothing made from nylon. But this blog post doesn’t address or evaluate those claims. The point here is that their emissions are > 0.