Whatever the outcome of today’s voting, we will learn something from it. And I will post some reactions to specific races and what they signify for stronger climate policy on 11/10 and succeeding days.

It is likely that around 70 million Americans (or more) will indicate their preference that Donald Trump be the next president. If the climate coalition defaults to inferences that the 70 million must be unethical people, or the dupes of utilities or oil companies, or otherwise willfully blind to the implications of their vote for the future of democracy, that would be a mistake — for all the reasons outlined in my book. But their votes will represent a body blow to democratic values like rule of law, respect for truth, and good governance nevertheless.

Most people have heard of the marshmallow test, a set of studies purporting to demonstrate that humans’ ability to delay gratification predicts their future success. The original study presented four-year-old subjects with a marshmallow that they could eat any time they want; but if they waited a designated amount of time to eat the marshmallow, they would get an additional marshmallow. The robustness of the original finding is disputed by scholars, but clearly there are situations in which humans will be better off if they consider not only their immediate objective but also the larger context and long-term implications of their choice. The “selective attention test” is another illustration of the power of immediate concerns to block out more important, less immediate concerns.

This is a critical thinking skill. We are wired to be hypersensitive to near-term threats and challenges. Therefore, considering those broader implications in the presence of the challenge takes more cognitive effort. It’s a skill that people develop through education, practice, and experience. But when the near-term threat is sufficiently frightening, most of us do not make that extra cognitive effort.

When it comes to energy transition policy, proponents of the energy transition see the expert consensus in favor of strong climate policy and conclude that opponents of the energy transition are failing the marshmallow test. Opponents of strong climate policy, by contrast, charge climate activists with focusing myopically on the benefits of a transition and missing its important costs.

Fortunately, in places where people have to deal with real energy problems, smart, competent people are making lots of progress answering the questions that each side of this fight poses to the other. But as we descend into bitter partisan tribalism and its focus on near term wins and losses, we lose sight of the looming threats to the health of our liberal democracy, and the importance of respect for truth, pluralism, rule of law, and fair political competition. Leading Republicans, including J.D. Vance, analogize the United States to “late republican” Rome awaiting its Caesar. And scholars have documented a sharp rise in right wing vigilantism. This is more than a little troubling.

Yet after the attempted assassination of Donald Trump, MAGA Republicans claimed that the shooter was triggered by rhetoric associating a second Trump presidency with undermining democratic norms. To those of us who worry about the erosion of bipartisan support for the rule of law, truth-telling, and fair political competition, that claim rings hollow. But many believe it nevertheless.

In chapter 6 of Climate of Contempt I cite a list of historians and other scholars of dictatorships who make the case that American democracy is in decline, and that a transition to authoritarianism can happen here. And nothing that has transpired since the book went to press to reassure me that a Trump victory will not further undermine the rule of law:

- Trump’s jury conviction on 34 felony counts (and multiple indictments in cases awaiting trial) did not dampen GOP voters’ enthusiasm for his candidacy.

- The Supreme Court held in U.S. v. Trump that presidents are immune from criminal prosecution for crimes they commit as part of their official acts, and erected additional evidentiary barriers to prosecuting presidents for crimes they commit outside of their official duties.

- The GOP selected a vice presidential candidate that has advocating firing all senior civil servants, and House Speaker who has vowed to “take a blowtorch” to the regulatory state.

The party’s nominating convention continued its recent tradition of characterizing rule by Democrats (and Democrats’ legally-enacted policies) as illegitimate. And a ridiculously long list of veterans of the Trump White House and GOP campaign operatives have testified to Trump’s moral and intellectual unfitness for office, and disrespect for fundamental democratic principles.

So, worrying about what David Brooks called our “democracy in decline” seems justified.

A meta-lesson of the research discussed in Chapter 4 of Climate of Contempt is that modern media distorts (and amplifies) our perceptions of immediate threats, making winning the next policy battle seem like a moral imperative. And ideological media can reframe any fact or event in ways that serve a near term political goal. As a consequence, longer-term values fall off of our mental radar screens because those people must be stopped.*

Entire internet communities now consume misinformation designed to frighten or enrage them, 24/7/365. That information diet triggers violence in some. In 2016 a man brought an assault rifle to a Washington, DC pizza place hoping to foil a fictional child trafficking and prostitution ring run by prominent Democrats. At his arrest he credited his actions to “bad information.” This year violent thugs attacked immigrants in English cities based on false information they acquired online, prompting an insightful response from exiled royal, Prince Harry:

What happens online within a matter of minutes transfers to the streets. … People are acting on information that isn’t true. For as long as people are allowed to spread lies, abuse, harass, then social cohesion as we know it has completely broken down.

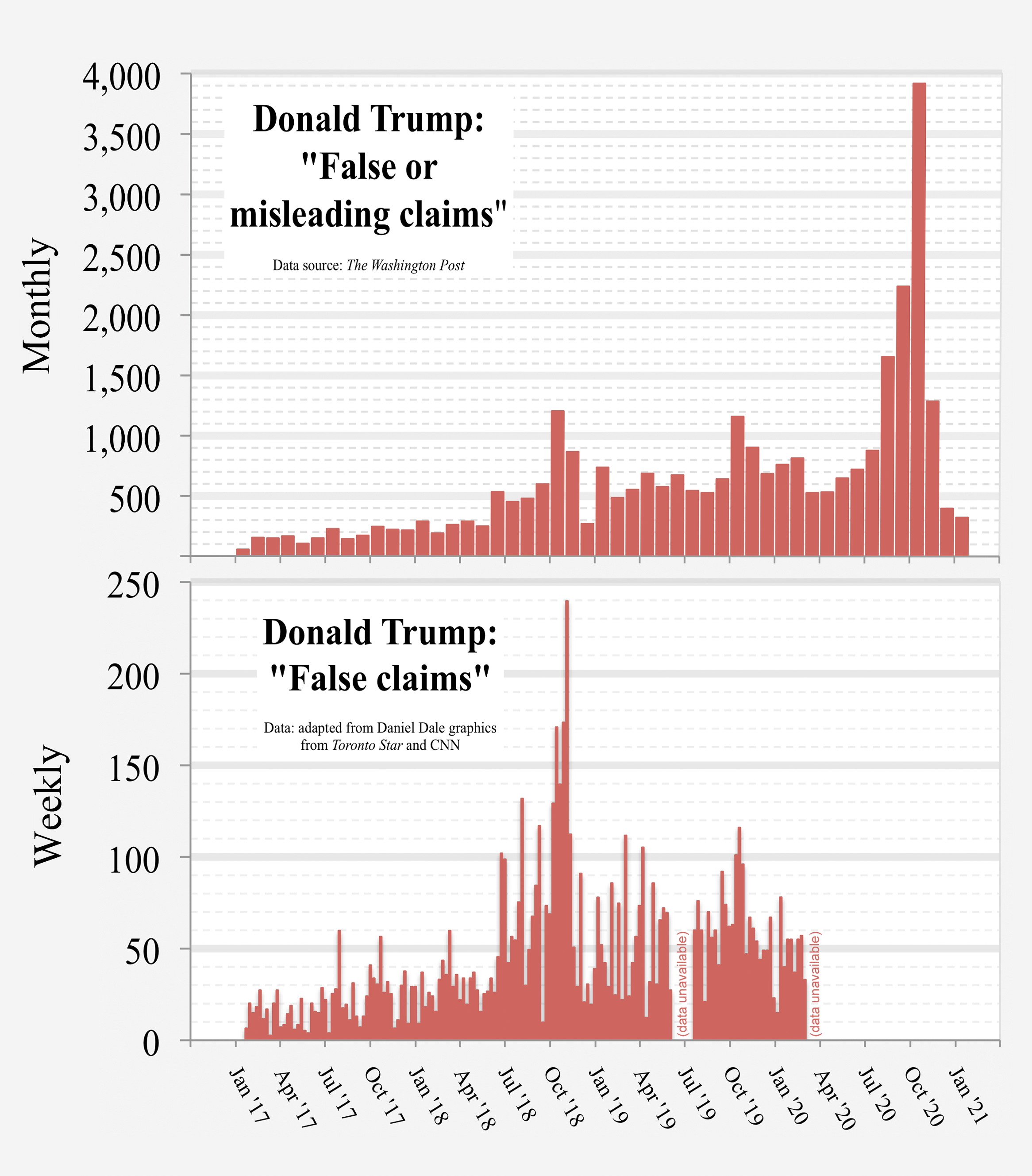

In the U.S., Democrats and liberals wonder why Republicans — leaders and voters — accept the obvious lying and venality of their standard-bearer, or justify their congressional representative’s vote to overturn the results of the 2020 presidential election, or reject the jury verdict in the criminal case against Donald Trump. Some Democrats assume that those choices reflect ignorance or character defects. And while Trump and his most cynical and famous media enablers do demonstrate an impressive array of human vices, research tells us that many GOP voters choose Trump because they believe he is the lesser of two evils — i.e., because ideological media has built Democrats and liberals into particularly frightening threats in their mind’s eye. (And while the two effects are not nearly symmetrical, there is a mirror image effect happening on left.)

The focus on winning prevents most conservative policymakers and politicos from acknowledging the danger of prioritizing policy victory over preserving liberal democracy. And conservative intellectuals who see the danger nevertheless embrace narratives that blame liberal, secular values in one way or another. American democracy may be in decline, but it is getting what it deserves.

For example, columnist David Brooks sees the “narcisism” of secular morality at the root of our troubles. Legal theorist Adrian Vermeule sees liberalism the way Marx saw capitalism, destined to be destroyed by irresistible destructive forces that it unleashes. To Vermeule liberal democracy’s primary virtue — its inexorable movement (halting and uneven as it may be) toward broader social inclusion — is its primary vice.

Yesterday the frontier was divorce, contraception, and abortion; then it became same-sex marriage; today it is transgenderism; tomorrow it may be polygamy, consensual adult incest, or who knows what. The uncertainty is itself the point. From the liberal standpoint, the essential thing is that the new issue provokes opposition from the forces of reaction, who may then be conquered in a public and dramatic fashion by the political mobilization of liberal forces.

In other words, the evolution of social morality is a process of bullying the defenders of the status quo into submission. It is not difficult to see how and why that view resonates so many of today’s conservatives. Never have a mob of bullies had the technology to shame others at the scale and speed that they have now. And the internet allows the rest of us to watch each and every time the mob oversteps the bounds of fairness and kindness, and to use that knowledge to justify our prior views.

So, it seems unlikely that conservative leaders will stop the threat to liberal democracy that MAGAism represents.** Only voters can do that, but the online media environment gets in their way. According to Pew Research’s latest findings on the subject, social media is at the center of how Americans debate politics, and Twitter/X is at the center of that social media discussion. A large academic literature illustrates how Twitter/X winds us up emotionally and misleads us about politics, and shields us from the kinds of experiences and information that prompt us to ask critical questions.

We are less likely today to have deep discussions of politics and policy across ideological and partisan boundaries. So we develop a less well-rounded understanding of the factual and normative aspects of political issues. Today’s politicians must “represent” that angrier, less reflective populace, one focused on defeating a political enemy. And we move farther away from a well-functioning liberal democracy and toward a future of more instability, poorer governance, and more political violence. Given the understanding of politics that voters get through the funhouse mirror of social and ideological media, they can’t see that coming. Finding a way to disrupt that distorted picture is the first step toward reversing the decline. – David Spence

————–

* For many voters these values may never have been on their radar screens. But what is surprising and alarming is that they have become so unimportant to pundits, voters, and others who formerly appreciated their value.

** The list of Republicans who oppose Donald Trump’s candidacy is lengthy — see here. But it includes only a SMALL minority of current GOP officeholders because GOP voters have punished most officeholders who stood up against Trump or MAGAism.

*** Now AI offers students and others opportunities to avoid the cognitive struggles that build their critical thinking muscles in the first place. AI may help a student write a better essay or poem or research paper or professional memo or legal brief, in which case the student earns a better grade – satisfying the near term objective. But that grade comes at the expense of the long term objective: namely, improving the student’s critical thinking skills.