[This is the second of two posts exploring what (if anything) we can learn about energy politics from the results of the November election. After this I will return to regular posting at regular intervals. — DS]

——-

In September I speculated about how each party’s energy messaging might play in competitive House districts in oil producing states. You can find that post here. This post makes good on the promise to revisit those races after the election. It also looks at what the election signifies about economic theories of voting and energy politics more generally.

Competitive Races in Oil Producing States

Did last Tuesday’s results offer any evidence that energy played a role in House election outcomes? VP Harris downplayed energy in her campaign. The GOP platform stressed “energy dominance,” and projected a message friendlier to fossil fuels. Did any of that matter in these particular races?

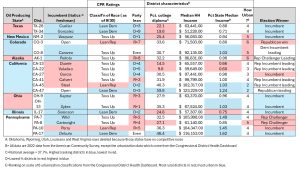

My September post speculated about competitive House races in oil producing states. Here is a modified version of the summary chart (from that earlier post) listing those competitive races. (Click on it to enlarge.)

Because all of these races were forecast to be competitive, it is not surprising that the Associated Press has yet to certify a winner in several of them. That said, other than the observation that many GOP candidates did better than expected last week, it doesn’t seem that we can really draw any broader conclusions from these results about the role of oil and gas jobs in driving votes.

Presumably, Donald Trump’s strong showing in Pennsylvania helped to flip two competitive seats there to the Republican column, and helped a GOP incumbent who is ideologically out of step with his district (Perry) retain his seat. Trump’s coattails may also be helping the three vulnerable Republican incumbents representing Democrat leaning districts in California to make a contest of their races. All of those races were anticipated to be tough ones for Republicans.

Nor is there much of an overall pattern in these results supporting the “rebellion against liberal elites” hypothesis. Looking at the table, in situations that pitted the partisan lean of a district against education level, results were mixed. In the two Texas races and IL-17, Democrats prevailed in districts with relatively low educations levels but leaned Democrat. Those particular results look inconsistent with the idea of the partisan “diploma divide.” But on the other hand, in CA-13 and CA-22, it looks like GOP incumbents may retain their seats despite the partisan lean toward Democrats, perhaps because of the diploma divide. Or maybe it was Trump’s coattails. Or maybe these districts simply demonstrate the incumbency advantage.

As I said in my last post, multiple narratives can explain many of these results.

Results in these races are similarly mixed with respect to the urban/rural divide and high/low income divide in this table. For example, Republicans are leading in two urban, high income districts (CA-45 and CA-47), one of which leans Dem and one of which leans GOP. So, teasing out the effects of the class. income, and educational divides will have to await more rigorous empirical study.

Did energy or climate messaging play a significant role in any of these races? It came up in most of these races, though other issues seemed more prominent in most of the campaigns. Most incumbents expressed some sort of pro-fossil fuel messages, as did most Republican challengers.

Democrat incumbents walked the line between their local oil industry constituents and their party’s support for the energy transition. Texas Rep. Henry Cuellar, for example, used social media to signal his friendliness to the oil industry and for energy transition technologies. And even though some Republican incumbents represented districts with both renewable and fossil energy industries, most signaled their support to the former more strongly than the latter – perhaps because wind and solar projects tend to produce fewer permanent jobs than fossil generators (per MW). For example, the national GOP tried to defend the California freshman incumbent David Valadao (whose race has not been called) by tying his challenger to locally unpopular energy policies pursued by California Gov. Gavin Newsom.

But as was true in the rest of the country, energy issues seemed to take a back seat to other issues — inflation, immigration, Trump’s fitness to lead, and culture war issues.

The Role of “Deliverism”

If oil and gas employment didn’t exert an observable pull on results, might local economic self-interest have played a role in other ways?

The Biden Administration has overseen a massive distribution of federal money to create jobs in industries related to the energy transition. If politics is mostly about economics — as an effort to capture economic benefits for oneself and to shift costs to others — that money ought to build support for Democrats and/or for the energy transition itself.

My book describes how this economic self-interest model of distributive politics is now bumping up against the 21st century rise of affective, negative partisanship. Thanks to partisan sorting of voters and the internet, most members of Congress protect their re-election is by voicing partisan animosity toward the other party and its agenda. For Republicans that now seems to include voicing opposition to green energy, even if it is bringing money and jobs to their districts.

Still, many in the climate coalition are hoping that distributive politics will reverse the trend toward affective partisanship in energy policy: i.e., that the largesse to red states and red districts from the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) and the 2021 Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL) will transform climate politics as those jobs materialize.

The next few congressional elections will give us a clearer picture of whether distributive politics is overcoming national partisan branding as a driver of election outcomes. It would be unfair to draw conclusions about deliverism from this election. The energy transition funding unleashed by the IRA and BIL is only just beginning to create the jobs and other economic benefits that might lead a critical mass of voters to prioritize climate policy in their voting decisions. The most we can say is that the early signs are mixed.

On the one hand, CNBC reporter Carl Quintanilla quoted someone at JP Morgan marveling at the inability of the “Harris team” to convert strong economic data into votes, including high “labor force participation,” “a surge in reshoring” manufacturing jobs, “an industrial policy that overwhelmingly benefits GOP districts,” and “wages rising faster than rents.” Republican House members who voted against the BIL and IRA happily take credit for bringing the benefits of those statutes to their districts, suggesting they see no electoral risk in doing so.

There are other signs that economic self-interest is losing importance in political calculations. For example, this year the Teamsters Union decided not to endorse Kamala Harris despite the Biden Administration’s delivery of significant benefits to the union under American Rescue Plan (ARP). In a series of September posts on Twitter/X about that decision, UC-Berkeley political scientist Jake Grumbach said this:

It is tempting to underestimate the power of the Internet propaganda machine to leverage human emotions and biases in subtly insidious ways, and to sustain false narratives. Ideas that seem ridiculously implausible to those looking in from outside of an information bubble are taken as articles of faith inside those bubbles.

A recent Politico/E&E News article (subscription required) described how victims of Hurricane Helene doubled down on implausible narratives in order to protect their political identities: Firsthand experience with a historic, climate-fueled hurricane has not inspired a reckoning with global warming in North Carolina, according to interviews with more than 75 residents in the disaster zone. Instead, survivors of the storm who already denied the existence of climate change are now turning to an increasingly prominent strain of disinformation.

According to those interviews, that disinformation includes the ideas that (i) the government used laser beams to steer Hurricane Helene toward an area it wanted to denude in order to access lithium deposits, (ii) “the Biden administration [is] diverting recovery funds to migrants while blocking aid from reaching Republican areas” and (iii) “missing persons lists were being doctored [and] dead bodies were being bulldozed under debris or trucked out of state” by the government.

On the other hand, around the same time that the Teamsters chose not to endorse a presidential candidate, 18 Republican House members sent a letter to Speaker Johnson urging the party not to repeal the tax credit provisions of the Inflation Reduction Act if they were to win control of the government, citing the benefits to their constituents from those provisions. And despite his promise to eviscerate the regulatory state, Johnson nevertheless signaled his intention to take a “scalpel not a sledgehammer” to the IRA. That statement, in turn, provoked a reaction from the House Freedom Caucus, who see the IRA as wasteful government handouts. (If Democrats retain control of the House, the question may be moot. But as of this writing Cook Political Report projects that GOP control is likely.)

All of which makes the signatories to the Johnson letter an interesting group to watch. We can try to infer their motives from their pre-election electoral circumstances, and we can watch how they behave when the GOP takes up the repeal of all or part of the IRA.

The table below (click to enlarge) summarizes the letter-signers’ ideology and electoral risk heading into last week’s election.

Signatories’ Rank Among the LEAST CONSERVATIVE (most liberal) of the 220 House Republicans?

Ten of the 18 represent swing districts or districts that “lean Dem” according to Progressive Punch. They know that the IRA is popular and so may be signalling their moderation to their moderate constituents. Consistent with that idea, 13 members on the list are among the 16 least conservative 200+ members of the House GOP caucus, according to both the Progressive Punch and Voteview.com ideology metrics. And a majority of those 13 are from solidly “blue” states. One of the few who is not, Marianette Miller-Meeks of Iowa, is Chair of the House Climate Caucus. None of these members voted for the IRA, so perhaps they believed they must distinguish themselves ideologically from the most extreme conservatives.

Of those ten swing and “lean Dem” states, three races are yet to be called by the AP, and four were won by Republicans. New York representatives Molinaro and D’Esposito lost their seats. Miller-Meeks is leading and the GOP incumbent won in the other “lean Rep” district.

By contrast, all the signatories representing “strongly Republican” districts won, unsurprisingly. That group includes the last four names in the table, staunch conservatives who represent solidly Republican districts (according to both Cook Political Report and Progressive Punch). They represent safe seats, so why are they willing to risk a primary challenge for defending a bill that conservative Republicans dislike? Or, alternatively, why do they see little risk in doing so?

The answer may be a deliverist one. According to Bloomberg, each of the four represents a district that received significant amounts of post-IRA clean energy investment — Amodei ($6.7 billion), Curtis ($550 million), Carter ($5.3 billion), and Houchin ($859 million). All four voted against the IRA.Maybe they worry about a backlash if it is repealed.

Of course, talk is cheap. The $64K questions is, would any of these Republicans be willing to anger the negative partisans who vote in primaries by voting against the IRA’s repeal? And if so, will they face serious primary challenges in 2026 if they do so?

Getting to net zero will require national legislation regulating greenhouse gas emissions. Last week’s results make that goal seem more remote. Nevertheless, the goal is popular, and it can be achieved (at least, theoretically) either by electing Republicans willing to vote for strong climate policy or by replacing Republicans who don’t with Democrats who do. So watching these letter signers may tell us whether or not the internet has made “all politics national,” or whether deliverism changes votes.

The IRA and BIL may yet transform climate politics. Even if they transform climate politics only in competitive districts, that may be enough to secure the kind of regulatory legislation that could make getting to net zero carbon emissions possible. But this election can also be read as a testament to the power of the Trump team’s messaging. If deliverism is to work as a political strategy, it will have to overcome the headwinds of propaganda. — David Spence

————-