Note: This is the third in a series of posts auditing the political analysis (and corresponding prescription) in Climate of Contempt. The first two were here and here.]

Longtime denizens of #Climate and #Energy social media communities will be familiar with the argument that it is Boomers who are standing in the way of a bolder climate policy and a more progressive politics. Some people see young Republicans’ professed support for a green energy transition (see here and here) and conclude that strong regulatory legislation will find its way through Congress when Boomers finally have exited this earth — and the voting pool.

Putting aside the attribution errors these sorts of generalizations trigger, the 2024 election cast some doubt on the blame-Boomers hypothesis. Many of the writers and pundits making the anti-Boomer argument are members of Generation X, and exit polls showed that GenX voters broke for Trump (54-45) more than Boomers (49-49) did. Still, Millennials and GenZ each broke for Harris, collectively 51-46. So the hope that young people will save climate policy is not extinguished.

Perhaps today’s young voters will turn out to be the kind of voters and political leaders who will prioritize regulating greenhouse gas emissions, either because more of them will join the Democratic Party or because more will be willing to reach across the aisle on that issue as Republicans.

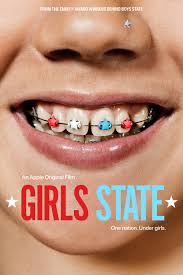

Earlier this year coverage of a new documentary film offered some support for that proposition. The film, Girls State, suggested that young people – or at least young women – might approach politics in more productive ways than their elders, offering hope for a return to a better functioning American democracy in the future. The film depicts a national summer camp on politics and governance for young women, and is a sort of sequel to the filmmakers’ earlier project, Boys State.[i] The BBC’s description of the documentary offers a flavor of the sort of hope it inspired:

One aspect [that filmmakers] Moss and McBaine did not anticipate was the nuanced nature of participants’ views on political subjects – which were often surprising. That diversity of opinions was reflected in participants such as Emily Worthmore, a conservative and daughter of a pastor who, while staunchly against abortion, believes in allowing other women to make their own choices on the matter. …

Yet one of the most refreshing elements was that those who disagreed showed compassion and respect. In one key moment, Worthmore and Cecilia Bartin, a liberal activist, have a lively yet civil debate on gun ownership. “There was a huge willingness to listen, that gave me a lot of optimism,” says McBaine.

NPR’s interview with the two filmmakers sounded similar notes:

[Interviewer Ayesha] RASCOE: What do you want the audience to take from both of these documentaries when thinking about teenagers and politics and how they grapple with issues?

[Filmmaker Jesse] MOSS: Well, I think we’re all curious about our future as a democracy. And I think these programs and these films are really tests of the proposition that we can find a kind of common ground and confront the existential problems that we have in our world and in our country. And we see, in both “Boys State” and “Girls State,” people actually trying to do politics in a healthier way than they do in the adult state. They look to listen. They look to build connections and find common ground, even around these divisive issues. They’re also not naive. They’re actually really smart and sophisticated about the world they’re sailing into, and yet they are not daunted. They are not cynical. They are really hopeful.

Those who have read chapters 3 and 4 of my book will already know why it is risky to extrapolate from the events depicted in Girls State to a real world future in which today’s teenagers inhabit positions of political leadership.

The key point is that Girls State participants need not worry about re-election. If they had to be re-elected, and they represented “safe seats” (like most members of Congress today), they would need to protect their re-election prospects by avoiding actions that displease the ideological extremists and negative partisans who vote in party primaries. Since re-election is not a concern for Girls State participants, they are free to explore solutions to complicated national problems through cross-party dialogue without worrying about accusations that they are fraternizing with the enemy.

In other words, this lack of accountability to voters allowed Girls State participants to problem solve better than members of Congress can. (Incidentally, this insulation from voter accountability is the same reason why regulatory agencies tend to produce better and more representative policy choices than Congress can.) In any case, until voters vote in ways that demand different behavior from their representatives, stronger national climate policy will probably continue to elude us. And until more of our political behavior and discussion moves offline, extremist negative partisans will continue to exert the lion’s share of influence over members of Congress.

Furthermore, younger voters’ support for Democrats last November wasn’t as strong as predicted. While young women voted Democrat at roughly the same percentages as in the recent past, young men voted Republican in larger numbers than recent presidential elections. A post-election Economist/YouGov poll indicated that 50% of 18-29 year olds have a favorable impression of the GOP, the same percentage that indicated a favorable impression of the Democrats. And young voters in swing states voted for Trump in larger numbers than in other recent elections.

So it remains to be seen how these countervailing forces will affect young voters in the future. Will the propaganda machine strengthen right populism among rural youth as it has their elders? Or will their belief in climate science withstand the propaganda onslaught? Perhaps in the coming years … as the costs of climate change hit younger GOP voters … and they see the national government turning a blind eye to those costs … and voters who already care deeply about climate change engage them in an ongoing dialogue about the issue … then perhaps national climate politics will change for the better.– David Spence

—————

[i] Boys and Girls state programs are more fully described in their Wikipedia entry here. The Boys State program has been held annually since the 1930s; Girls State is of more recent vintage. The documentary producers previously produced a film covering the Boys State national meeting.