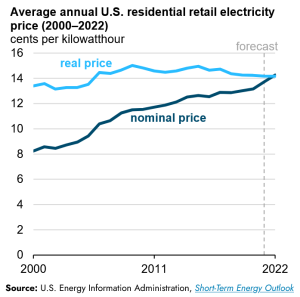

The U.S. electricity system has enjoyed several decades characterized by flat (overall) demand, sharply declining costs in less polluting forms of generation, and the presence of firm, mostly legacy gas-fired backup generation on the grid. In most places, these forces have kept rates relatively stable for a long time.

Now we face an era of sharp demand growth led by AI servers, the closure of older, inexpensive sources of firm generation, more intense severe weather events due to climate change, and high political barriers to building the transmission connections that would tamp down shortages and the price spikes they trigger.

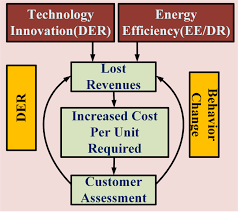

The price of electricity service has become a political hot button issue in wildfire-ravaged California, the mid-Atlantic states of the PJM region, and New England, especially Connecticut. As the price of solar panels and batteries fall, some foresee a utility death spiral — customers exiting the grid in favor of self-supply — in places where electric rates are high and solar power is cheap. As customers exit the system, the costs must be spread over a shrinking number of remaining captive customers. Hence the phrase “death spiral.”

It can be human nature to downplay the hard tradeoffs at the heart of the energy system when trying to enlist others in a reform cause. Many (but not all) economists succumbed to it when urging the restructuring of electricity markets three decades ago. They understood that competitive markets posed the risk of under-investment in supply and more price volatility. But they were optimistic about managing those problems, so they underplayed those risks.+

More recently, proponents of a rapid energy transition sometimes succumb to this same temptation, if only by ignoring (rather than denying) the practical difficulties of ensuring that the transition doesn’t exacerbate energy poverty in the U.S.. While there are scholars focusing hard on these issues, the set of scholars and experts who advocate a less grid-centric electric system in the U.S. are not always attentive to this risk. But they should be, because it is the kind of risk that is often top-of-mind for politicians and policymakers.

It doesn’t take much imagination to recognize how economically regressive it could be for a cascade of well-off customers to exit the grid. In the first place, it would raise prices for those left behind, and high energy prices are harder on those with fewer dollars. They are less able not only to pay higher energy bills, but also to access capital necessary to exit the grid. In public utility law, this is known as “the Market Street Railway problem.”*

And if electricity demand growth outpaces supply growth, prices will rise further. There are lots of good ideas about how to remedy that problem, but they all require political will. In a litigious, NIMBY world, political will sometimes lags (or derails) investment in supply.

For a long time too many scholars and policy wonks acted as though the energy transition will be only good news for the economically-vulnerable, because that population tends to bear the brunt of fossil-fuel pollution. But high prices and price volatility are another kind of cost that burdens the poor more than the rich. Price volatility is a feature (not a bug) of competitive electricity markets, and increased reliance on more weather-dependent generation can exacerbate that volatility.

Better demand management can help, but is probably not the solution during the severe weather events of the future. And some of those demand management solutions would put more responsibility on customers to provide for themselves when supply constraints raise prices. But those sorts of solutions will also favor the relatively wealthy and sophisticated consumers — those with the wherewithal to hedge price risk, supply their own backup power, invest in demand management systems, etc.

That may be a future that leaves the poor behind. Ideally, policymakers won’t let that happen. One good way to make sure of that is to talk about those risks, to be open and transparent about them. — David Spence

———–

+If you would like to dive into these issues more deeply, economist James Bushnell recently blogged about these problems here. I wrote about them in 2008 here. Before that, LADWP leader David Freeman testified before Congress about them, here. And before that, economist Paul Joskow wrote about them here.

*Ask you AI assistant about this problem and there is a decent chance that it will give you a clear and succinct answer. The case from which the name comes is here: https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/324/548/.