All News

What’s with the pivot toward natural gas?

So far 2025 has seen a lot of “pivoting” away from clean energy and toward natural gas. Los Angeles Times writer Sammy Roth recently documented one such pivot, by wind energy champion and conservative billionaire Phil Anschutz. Tech industry giants who led the charge toward procuring “100% clean energy,” like Meta and Google, are also exploring the use of natural gas to power their energy-gobbling data centers (see e.g., here and here). Some utilities may be backing off their aggressive decarbonization goals, and BP has “dropped its green pledges” in favor of more focus on its core oil and gas business.

Nor are these pivots limited to the private sector, or to red states. A California regulator recently rejected a smog-fighting proposal to phase out gas appliances, citing affordability concerns. High electricity rates in New Jersey have gubernatorial candidates there distancing themselves from Governor Phil Murphy’s energy transition policies. The State of New York may be poised to approve construction of a natural gas pipelines connecting gas production centers in Pennsylvania with demand centers in New England, something the State has steadfastly refused to do since it banned the use of fracking to produce gas in 2015. Some other blue states are relaxing their decarbonization plans in various ways. And New Zealand has reversed its ban on offshore oil and gas production, citing worries about natural gas shortages.

What is going on?

The reasons behind these pivots are many and varied, but two factors figure prominently in the answer to that question. One is that consumers place a higher priority on reliable, affordable energy than on clean energy. In some situations decarbonization plans are in tension with those other goals, depending how market rules influence the availability and cost of backup power from less weather-dependent sources. Politicians and firms know this, and their futures depend upon keeping those consumers happy.

The other is that the Trump Administration is leading a multi-pronged, ferocious GOP attack on renewable energy and the very notion of a clean energy transition. It has triggered a precipitous drop in GOP support for renewable energy over the last five years, one that includes young Republicans. This may be an example of partisanship driving views, and seems consistent with GOP’s increasing tendency to define itself in opposition to what Democrats want. Companies see this happening too, and they are adapting to this new reality.

Does that mean that the energy transition is doomed? Certainly not, though it will be slower than some had hoped.

After a long period of rallying rhetoric in the discourse around the clean energy transition, more and more Democrats are now willing to talk openly about the tradeoffs between rapid decarbonization, on the one hand, and energy reliability and affordability, on the other. Suddenly the term “energy abundance” is everywhere, and its popularity is a partly an acknowledgment that no transition will happen if voters associate it less available or more expensive energy.

In the long run more transparency will be helpful, and will make the energy transition more durable. Meanwhile, the long list of solar, wind and battery projects seeking to interconnect to the grid demonstrate that there remain win-win opportunities to invest in clean energy. Repeal of all or parts of the Inflation Reduction Act will reduce the number of those opportunities, but there will still be many places where they can be had.

Some low carbon technologies may even get a boost from the new regulatory environment. The Trump administration seems to like nuclear power and to hate regulation. So, it may be willing to lower regulatory barriers to approving new nuclear powerplant designs or construction of new plants. And the new Secretary of Energy seems to like geothermal power, and seems inclined to want to hasten its development. Both of these technologies promise relatively firm (or dispatchable) carbon free power at the generation stage, and both need a boost to compete on price in electricity markets. So far, it looks like the Trump Administration may give them that boost.

At the same time the GOP’s sharp turn against clean energy is producing some nonsensical decisions and policy proposals. The president has ordered several inefficient coal-fired power plants that would otherwise have retired to remain open. This is a lose-lose proposition. Not only is coal-fired electricity more damaging to human health than any other electric generation technology, it is one of the more expensive technologies as well.

Not to be outdone, some red state legislatures have considered bills that would both increase electricity costs and jeopardize electricity reliability. A bill came dangerously close to passage in the 2025 Texas legislative session that would have required existing renewable energy power plants to have back up back up power supplies (other than batteries) to provide energy when the sun doesn’t shine and the wind doesn’t blow. In the end the bill failed, presumably because it would result in the loss of generating capacity at a time when growth in demand is skyrocketing. (See Doug Lewin’s Texas “grid roundup” site for the best coverage of these issues.)

Ironically, the same data centers and other forces responsible for projected increases in electricity demand may be protecting existing and proposed wind and solar projects from the GOP ax. These projects help keep the lights on, and they are cheap to operate. That they require backup from less weather-dependent resources doesn’t change that fact. Furthermore, building more natural gas-fired generation will take time, because natural gas turbines are on multi-year back order.

These are the sorts of real-world constraints that intrude on the neat pro- or anti-clean energy narratives that dominate much of the public discourse. This is an auspicious time to transition to cleaner forms of energy; but that task nevertheless requires tradeoffs. Many of the Trump Administration’s attempts to put a thumb on the scale for fossil fuels have no business or public policy justification. At the same time, the pivot toward natural gas is also partly a concession to need to provide consumers (a/k/a voters) with affordable, reliable energy in a time of historic growth in electricity demand. – David Spence

“There’s reason in the kindness”

A few weeks ago was graduation weekend at the University of Texas, during which I had the occasion to walk from the law school (in the northeast corner of campus) to an appointment at the business school (at the southwest corner). In that 15 minutes I passed by many joyful families and graduates, celebrating, taking pictures, etc. My brain was flooded all at once with reminders that:

- higher education is a privilege, one that is not available to everyone

- I am fortunate to be part of the system that delivers that education to appreciative students and families

- The quality of American universities attracts students from all over the world, and

- Bringing together students with a diversity of viewpoints, backgrounds and experiences is part of what makes our universities great.

My walk took me past people speaking, English, Spanish, Arabic, Chinese, and two or three other languages I didn’t recognize. I am proud that the University of Texas attracts bright and eager young people from all over the world who want to learn, and to carve out a successful path for themselves. Some of them come from countries that have never seen democracy, yet they get to experience American democracy for a while. And it has been my privilege to watch those students come to grips with its messy complexity.

On that walk I also thought about how higher education is under attack. The Trump administration is (i) taking an ax to the institutions that fund research, (ii) using its power to threaten institutions of higher learning, (iii) revoking visas of foreign students for their speech, and (iv) even snatching legally-present foreign students off the street for detention or expulsion without due process. As I walked, a wave of emotion came over me thinking about all of those things at once.

In the early 2000s I was fortunate to take students on three occasions to Central European University (CEU) in Budapest, Hungary. That institution was founded to promote liberal democratic values in post-Warsaw Pact nations. It is difficult to describe how inspirational and eye-opening those trips were. Of course, since then CEU has been forced out of Budapest by Viktor Orban, and American conservatives have embraced both Orban’s authoritarian ways and his (perhaps anti-Semitic) demonization of CEU’s American founder.

For a long time I have written about about the erosion of the foundational Enlightenment values on which our democracy depends, and its impact on policy. Now we must worry about protecting universities’ role in promoting and exemplifying those values. The Internet makes that harder to do, by making us more likely to misperceive each other and the world — something scholars call “pluralistic ignorance.” Feelings of alienation from politics are driving people away from liberal democratic values and toward the political ideologies that treat adversaries as enemies, worthy of neither civility nor respect. That is a worrying trend because demonization begets more demonization, in a self-perpetuating cycle.

The title of this post is a lyric from a song I once wrote about the historical rise of those liberal democratic values: i.e., about the connection between pluralism and respectful, reasoned discussion, on the one hand, and a freer, stronger and kinder society, on the other.[1] Enlightenment philosophers were explicit about the value of pluralistic, liberal democracy as a vehicle to facilitate and cultivate the connection between reason and kindness, and thereby to produce good government. Historian James Buchan described the Enlightenment this way: “A new theory of progress, based on good laws, international commerce and the companionship of men and women, displaced the antique world of valour, loyalty, religion, and the dagger.”[2]

That system is fragile, and it depends upon respect for truth and each other, and upon the marketplace of ideas to expand the store of available knowledge. If we kneecap research and deny some segments of society access to that higher education, it slows the search for new understandings.

The Administration’s assault on universities appears to be part of a broader strategy to weaken institutions that might challenge its apparent authoritarian intentions, and there is plenty of evidence to support that idea. But another part of the assault is based on the idea that it is universities that are censoring ideas by denying a platform to conservative thought. This “universities as left-wing indoctrination centers” narrative is mostly wrong, but only mostly. It is popular on the right in part because it serves the political purposes of those who promote it, but also because there are two kernels of truth floating around within it.

One is the fact that university faculty contain a much smaller percentage of conservatives than the general population, especially within certain departments and disciplines. A seminal 2006 study found that only 9 percent of university faculty identified as “conservative,” with the remainder split evenly between “liberal” and “moderate.” Another, contemporaneous study found especially high ratios of Democrats to Republicans in the humanities, and lower ratios in professional studies and science and engineering.

While there are explanations for this distribution that go beyond bias in hiring, the fact remains that conservatives on campus — faculty and students — feel like a small minority because they often are. However, it does not follow from that that liberal professors squelch or fail to acknowledge or develop ideas associated with conservatism. To the contrary, the vast majority are conscientious about creating a classroom environment that is open to all views.

Yet students today apparently feel uncomfortable speaking freely in class, and wide swaths of the public believe that university environments are more friendly to left-leaning than right-leaning expression. I suspect that if and when faculty send that kind of signal to students, most do so unconsciously rather than intentionally. And students’ use of social media to try to sanction other students for in-class speech exacerbates the sense that speaking up is risky. These are important challenges that university faculty and leadership are working to overcome. They neither endorse these dynamics nor are they indifferent to them, in my experience. But they remain a problem.

The second kernel of truth in the GOP assault on universities is that some academic paradigms do serve to suppress ideas by ruling out of bounds (read: delegitimizing rather than engaging or refuting) a much broader set of ideas than the set excluded from first amendment protection. This so-called “woke-ism” issue has been the subject of intense press scrutiny for a long time, and the GOP has leveraged it to its electoral advantage.

One byproduct of this line of thought is that universities have split over whether and when to sanction speech that causes serious offense in the listener. At one pole are free speech absolutists who believe that the freedom to express (and the ability to cope with hearing) offensive speech is a central part of the educational process and a pillar of academic freedom. The so-called Chicago Principles are perhaps the best expression of this point of view. At the other pole are proponents of postmodern or critical studies ways of thinking about speech-as-violence. According to this view, speech that offends too deeply ought to be sanctioned, just as the ,aw sanctions hostile environment sexual harrassment.

This fight has become sufficiently intense to divide, often sharply, the organizations that support academic freedom. The Associations of American University Professors (AAUP) and the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE) each claim to be dogged defenders of academic freedom, but their views of what that means differ significantly (see here and here). The Academic Freedom Alliance (AFA) appears to sit somewhere between AAUP and FIRE on these issues, though both APA and FIRE were formed in partial reaction to the AAUP’s stances on these issues.[3]

Contrary to popular opinion, this divide doesn’t map neatly onto partisan divisions. While conservative academics tend to support the traditional, broader definition of beneficial speech,[4] so do many left-leaning academics. That has been the case from the first late-20th c. flowering of postmodern ideas about speech. One illustrative example is law professor Dan Farber, no conservative, who in 1997 co-authored a ferocious book-length attack on postmodernism’s redefinition of acceptable speech, calling it a “radical assault on truth.”

Nevertheless, the perception persists that left-leaning academics pose a threat to students’ ability to think and speak freely. That perception may be feeding support for Donald Trump despite the Administration’s unprecedented attacks on universities and the presence of foreign students therein. Right now, that support is producing harm to the basic research that benefits society and to the environment that has made American universities the envy of the world — an envionment that is open and broadly welcoming to both ideas and people. If Republicans manage carry that threat to its logical conclusion, that will represent a preventable and historic tragedy. — David Spence

————

[1] You can find a recording of that song here. The full chorus lyric is “There’s peace within the silence / And reason in the mind / There’s reason in the kindness / So remember to be kind.” The song is also an ode to the City of Edinburgh, a place whose political philosophers played such a key role in the formulation of the Enlightenment values that influenced the drafters of the U.S. Constitution.

[2] Buchan, James. 2007. Capital of the Mind: How Edinburgh Changed the World. Edinburgh: Birlinn, p. 2.

[3] My University of Texas colleague David Rabban has published a comprehensive exploration of these various meanings of academic freedom, and its relationship to the first amendment. You can find that book here.

[4] Many GOP politicians, on the other hand, seem to embrace free speech selectively, condemning anti-Semitic speech more eagerly than other types of speech that offends.

Problem-solving > Blame

It is no secret that ideological and social media have amplified the worst of human nature in many ways. One away it does this is to supercharge the human instinct to blame a group for the bad acts of its individual members, and to endorse punishment of all the members (or every member) of that group. Writing about the recent violent attacks on U.S. Jews by people angry about Israel’s violent oppression in Gaza, New York Times editor Jonathan Weisman wrote:

There is a useful distinction between the clear bigotry of Jew hatred and the political and historical debate over Zionism … But attacks on Jews for the actions of an Israeli government a world away are collective punishment, and collective punishment is bigotry.

Yes, collective punishment is bigotry.

In my book I describe this notion more dryly as an attribution error, one often produced by the logical fallacies of composition and division. Perhaps it is an instinct wired into us from our days surviving in groups on the savannah. Whatever its origins, we are too quick to assign group blame in this way, particularly when we are angry or afraid. And the Internet is the most effective tool in human history for cultivating and steering fear and anger. Indeed, it trains its denizens in the art of “rage farming,” using censored ideological messaging, our instinct to flock to ideological kin groups, and appeals to negative emotions.

So, anger at Israeli violence in Gaza has begotten attempts to assassinate American Jews, some of them successful. Anger at the U.S. health care system has made another assassin a hero to thousands (perhaps millions) of angry Americans.[i] And the nativists managing immigration policy in the Trump administration try to get us to think of undocumented immigrants not as refugees or economic migrants but as “invaders“ and gang members. That way, we are more likely to accept the abduction of immigrants off the street by plain clothes groups of armed, masked thugs, or the deportation of migrants to brutal El Salvadoran prisons.

So much of political debate on social media appeals to our lesser angels because it is effective. It relentlessly builds the case for the immorality of the other group, and why its members deserve our contempt. But this constant rage farming is making us dumber about politics and policy, focused more on who we hate than on devising workable policy responses to complex problems, including climate and energy problems.

The future of democracy depends upon breaking this cycle of escalating hatred. The question is “how?” I don’t know exactly, but I do know that this is a bottom-up problem. Therefore, one constructive step we can each take is to help each other to recognize rage farming and its destructive effects, to discourage it online, and to elevate voices focused on solving problems over those focused on group blame.

One such voice is former Prime Minister of New Zealand, Jacinda Ardern. Ardern said the following this week on the Stephen Colbert show:

We have choices in leadership, particularly in politics. When you’re in times … when people have fear and uncertainty, you can either weaponize that [and] appeal to people using fear and blame, or you can actually tackle the issues that are affecting people’s lives. And you can do it with … kindness and empathy, and strength, and courage, and resilience as well.

I hope people will watch the clip and the audience’s reaction to it. Perhaps more people are tiring of blame-hatred politics. I hope so. Ardern’s message is not unlike the approach advocated by U.S. politicians like Cory Booker and Pete Buttigieg. But if we hear their words as advice directed only at the other side, we will have missed the point entirely. – David Spence

————

[i] The results of this YouGov poll offer a deeper dive into the appeal of Luigi Mangione to his fans.

Strongly worded letters and the Inflation Reduction Act

Over the last few months Republicans in Congress have been writing strongly worded letters to each other about the various green energy subsidies created by the 2022 passage of the Inflation Reduction Act. In early March, 21 House Republicans urged Speaker Mike Johnson not to repeal the IRA in its entirety. About a month later four senators expressed a similar sentiment to congressional leaders. About a month after that, 38 other House Republicans urged the speaker to “fully repeal” the IRA.

We can understand each of these dueling letters – and members’ upcoming votes on IRA repeal – as the product of the way each of the signatories experiences bottom-up pressure from voters.[1] Members sign letters like these – or choose not to sign – based mostly on how the decision will affect the probability that they will be re-elected.

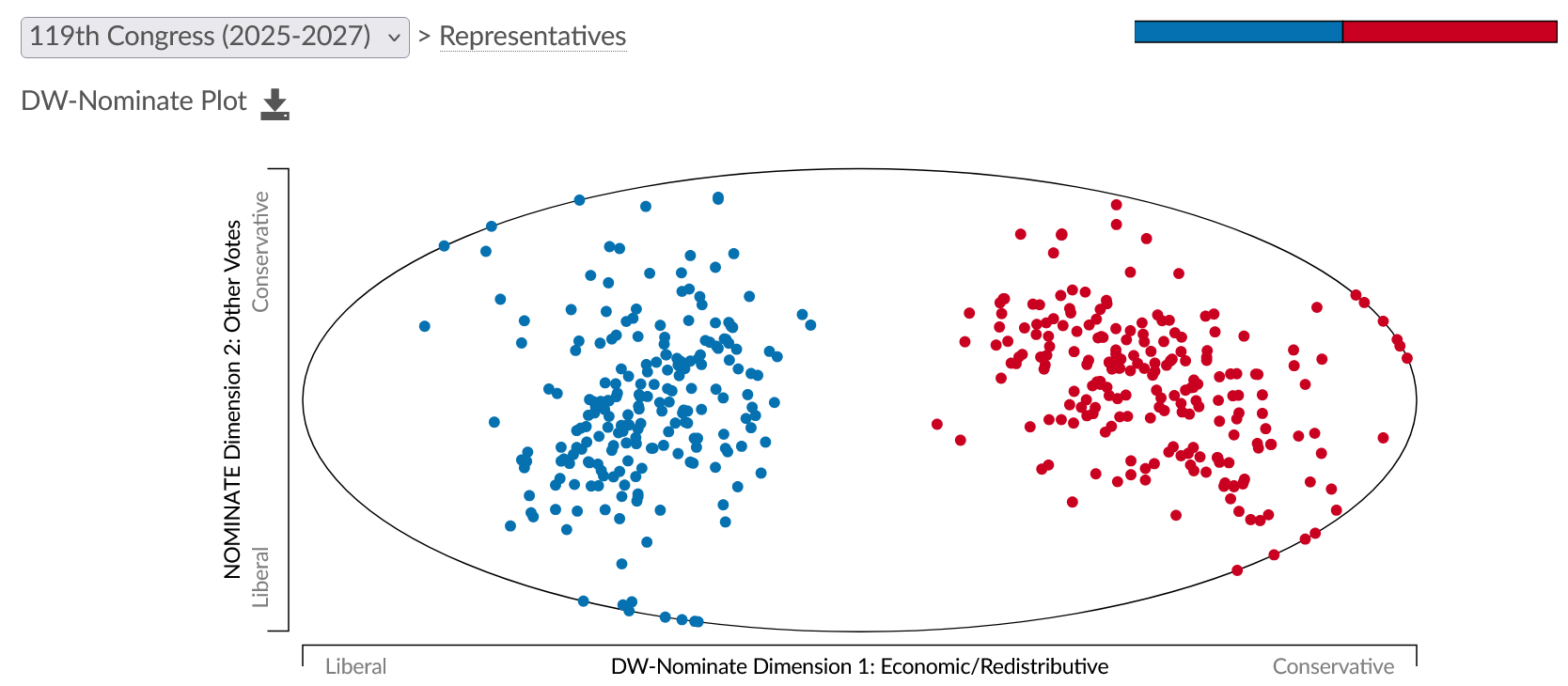

As mentioned many times before in this space, the primary reason that Congress is more ideologically polarized than the electorate is because most members represent safe seats: seats in which voters of one party or the other are so numerically dominant that the candidate of that party cannot lose the general election. These members protect their re-election prospects not by keeping their average constituent happy but rather by keeping the average primary voter happy. Primary voters, in turn, are much more negatively partisan and ideologically extreme than both the average voter and the average member of their own party.

Knowing all this, we can take a more educated look at who signed each of the two House letters? (We will ignore the Senate letter because only one of the signatories – Sen. Thom Tillis, R-NC – is up for re-election in 2026.) Do the signatories line up neatly along ideological lines? Do the signers of the anti-IRA letter represent safer GOP seats than the signers of the earlier pro-IRA letter? Does the amount of IRA funding that flowed (or was intended to flow) to their districts explain these decisions?

Helpful Data

IDEOLOGY: Political scientists measure the ideology of members of Congress on a left-right scale, and leading measure comes from a web site called Voteview.com.[2] That measure runs from -1 (most liberal) to +1 (most conservative). Today the average House Democrat sits at -.38 and the average House Republican at +.52; and there is no ideological overlap between the parties. Indeed, there has been no overlap for almost two decades, and the ideological gap between the most conservative Democrat and the most liberal Republican has grown since.

SAFE SEATS: The Cook Political Report is the leading measure of the “partisan lean” of a district. Cook’s 2025 PVI by district can be found here (though some of the data is behind a paywall).

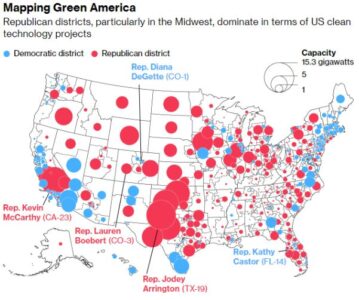

IRA FUNDING: It has been widely reported that more IRA funding has gone to GOP districts than Democrat districts, though not every district has benefited from that statute’s largesse. The Trump Administration is in the process of trying to claw some of that money back. But as of August 2024 the consultancy E2 had matched IRA projects to congressional district, specifying number of projects, dollar values and number of jobs for each. That report can be found here.

[NOTE: None of the signatories to either letter appear among the top House recipients of money from the fossil fuel industry. See e.g., here and here.]

What do the data show?

This table lists the signatories to both House Republican letters, sorted by voteview ideology score – from most to least conservative. Signers of the pro-IRA letter are shaded green; signers of the anti-IRA letter are shaded red (click on table to enlarge).

Eyeballing the table a few things stand out. As a group, the signers of the pro-IRA letter are significantly more liberal than the signers of the anti-IRA letter. Recall that the average ideology score for House Republicans is +0.52. The average signer of the pro-IRA letter has a score of +0.34; the average signer of the anti-IRA letter has a score of +0.71. Not coincidentally, the anti-IRA letter signers represent districts that lean Republican by an average of more than 12 points, while the pro-IRA letter signers represent seats whose average partisan lean toward the GOP is less than 3 points. Neither group appears to have received significantly more IRA project funding or jobs than the other.

This is consistent with the idea that the signatories of the pro-IRA letter are protecting their re-election prospects by signaling their support for the IRA to their constituents, in the hope that it will matter in the relatively competitive general election they face in 2026. Those who signed the anti-IRA letter, in turn, protect their re-election prospects by pleasing their own party’s primary voters.

Still, there are some interesting exceptions in the table. Representatives Buddy Carter (GA-1), John Joyce (PA-13), and Erin Houchin (IN-9) are each more conservative than most of their Republican colleague, but each signed the pro-IRA letter. We can speculate they did so because their districts will gain jobs and money from IRA programs. Perhaps so, especially for Rep. Carter. Of the people listed in this table, no one’s district gained more projects as the result of the IRA, and the district ranks second in jobs and money gained from IRA programs.

On the other hand, several signers of the anti-IRA letter represent districts with much to gain from the IRA. The IRA was slated to bring 15 new projects, more than $10 billion dollars, and about 3,700 new jobs to the districts represented by Reps. Brecheen (OK-2), Spartz (IN-5), and Norman (SC-5). Yet all three endorsed “full repeal” of the IRA. Perhaps their choices are purely ideological. Norman and Brecheen have especially conservative voting records — even more conservative than Rep. Carter. And both represent seats that are safer than Carter’s.

But what about Rep. Spartz? Her seat, like Carter’s is rated R+8 by Cook Political Report. And like Carter her district stands to gain economically from the IRA. But she and Carter have staked out opposite positions on IRA repeal.

Spartz, Brecheen and Norman may be betting that flouting the president’s anti-green energy agenda carries more electoral risk for them than protecting the money and jobs the IRA is bringing to their constituents. Rep. Carter may simply be making the opposite bet. Or maybe Carter just believes that the IRA subsidies are good policy, and is willing to risk the president’s wrath. Regardless, it will be interesting to see if their positions affect their 2026 election campaigns. Will Spartz face risk in the general election for biting the hand that fed her district? Will Carter face a primary opponent who takes him to task splitting with the president on this issue?

The Fate of the IRA

For all of these reasons, the people to watch in this fight are the members who represent competitive districts. The things they have to do to protect their re-election prospects in the general election increase their electoral risk in a primary election. Some politicians navigate this difficult reality by signaling their “concern” about partisan legislation, while voting with their party when push comes to shove. (See e.g., Sen. Susan Collins, uses this technique so frequently that one news outlet called it “a meme.”)

As of this writing the House Ways and Means Committee is close to releasing the (budget) bill that will likely repeal some or all of the IRA energy subsidies. And in the last few days the signers of the March letter defending the IRA have been active. Rep. Jen Kiggans (R-VA) introduced a bill that would eliminate IRA tax credits for wind and solar generation, perhaps as a way to divert Republican energy away from broader IRA repeal. Several signatories of the March letter signed a May 9 letter to the Ways and Means Committee urging retention of the IRA “45X” tax credit for green manufacturing, and several are also co-sponsors of Kiggans’ bill. And one of the signatories to the Senate letter defending the IRA, Sen. Lisa Murkowski, aggressively defended carbon capture subsidies in the IRA in recent Senate hearings.

Assuming that the bill that emerges from the Ways and Means Committee repeals many but not all of the IRA subsidies, it will call the bluffs of each of the authors of these strongly worded letters. And it will reflect the GOP leadership’s best guesses about which GOP faction is making the more credible threat to break ranks if it doesn’t get its way. At that point, defenders of the IRA will have to decide which is the greater risk: defying a president and party that has turned against supporting the clean energy transition, or defying moderate voters in their districts who favor it.

My best guess is that they fear the former more than the latter, because the MAGA faction of the GOP has been willing to punish dissent than have the GOP voters who vote in general elections. But we shall see. — David Spence

———————

[1] See this earlier post examining the election results in a similar way.

[2] Lewis, Jeffrey B., Keith Poole, Howard Rosenthal, Adam Boche, Aaron Rudkin, and Luke Sonnet (2025). Voteview: Congressional Roll-Call Votes Database. https://voteview.com/

On Billionaires and Bullies

Climate of Contempt bemoans the way ideological and social media encourages and supercharges the human instinct to make attribution errors in politics. These errors involve a number of logical fallacies I describe in the book, and they often take the form of assigning blame to the wrong person or to the broader group of which the right person is a member.

So, with that in mind, let’s talk about billionaires.

Economic Inequality

Just about every measure of economic inequality shows its steady increase in the United States since the last quarter of the 20th century. The United States now has roughly 800 billionaires, up from 66 in 1990.[i] And the share of wealth controlled by the richest 1 percent has grown from about 23% to about 30% over that same period.

For all their wealth, until recently today’s billionaires paled by comparison to the Robber Barons of the Gilded Age, at least when measuring their wealth against national GDP. But that has changed. Elon Musk has leapfrogged John D. Rockefeller to top that list, though (except for Bill Gates) early 20th c. industrialists still dominate its upper reaches. But tech billionaires have been gaining on the Robber Barons over the last two decades.

The massive accumulations of wealth in the hands of a few naturally rankles, especially when accompanied by the claim that the U.S. cannot afford the kind of investments in infrastructure, public health, environmental protection and a social safety net that most other first world nations make. Stark inequality is one of the drivers of populism – “every billionaire a policy failure” – and generates hilarious parodies like this one.

Economists disagree about the key drivers of inequality, but it coincided with the late 20th c. rise to dominance in policymaking circles of ideas from public choice economics.[ii] These ideas included increasing faith in the self-correcting nature of free markets, lower marginal tax rates, and skepticism toward government regulation. When Ronald Reagan assumed the presidency in 1981, the marginal tax rate on the highest earners was 70%; when he left office it was 28%. (It had reached more than 90% during the Eisenhower era.) The conservative economic theories embraced by Reagan, Margaret Thatcher and others fed deregulation of the utilities, finance, and transportation industries, but they found their fullest flowering in antitrust law.

Antitrust and Competition

For much of its first century, antitrust law treated big firms’ use of their market power to destroy smaller competitors as illegal. John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil used its leverage over railroads and retailers to force other producers of oil products to sell their companies to him in exchange for Standard Oil stock. In response to his bullying, the Supreme Court ordered the company broken up into 34 parts in 1911.[iii]

Eight decades later, however, federal courts declined to break up Bill Gates’ Microsoft Corporation, despite finding that the company had engaged in almost identical forms of bullying. Why? Because in the intervening period many antitrust enforcers and judges had become convinced that the market will discipline tech monopolies that abuse their monopoly power. This modern era of light-touch antitrust enforcement has coincided with increased market concentration in most industries, yielding (according to one NYU study) “higher profit margins, positive abnormal stock returns, and more profitable M&A deals, suggesting that market power is becoming an important source of value.”

Interestingly, many (most?) of the tech billionaires whose companies rose to dominance during this time identified with the ideological left, professing progressive ideals (including a dedication to clean energy) and other social aspirations summed up by Google’s original “don’t be evil” motto. Indeed, as I show in Appendix D of my book, as recently as 2022 political giving by those on the Forbes list of the 25 wealthiest Americans was fairly evenly split between the two parties. But while Kamala Harris did very well with super-rich donors in the 2024 election cycle, the wealthiest tech billionaires flocked to Trump.

The reason may have to do with antitrust law. And bullying. And the art of the deal shakedown.

Recovering Older Notions of Market Power Abuses

When I taught the U.S. v. Microsoft in class this year some students were surprised by the facts of the case; one reacted by saying, “Bill Gates must have a great P.R. staff.” But the trajectory Gates’ career has followed mirrors those of Rockefeller, Andrew Carnegie and many of the 20th c. Robber Barons:

Step 1: Grow to dominance by innovating and persevering.

Step 2: Use monopoly power to destroy competition and gain unfair advantages in new markets.

Step 3: Retire and spend decades mastering the art of strategic philanthropy.

Today’s dominant firms, like Google and Amazon, are still in Step 2. They are using their monopoly control of one product market to (a) gain unfair advantages in related markets, and (b) continue to crush those who would compete in the market they dominate.

Biden Administration antitrust enforcers, particularly Federal Trade Commission head Lina Khan, saw these kinds of activities the way early 20th century enforcers did: namely, as abuses of monopoly power. The Biden Administration filed multiple suits against Google and won some victories (see here and here). A similar suit against Amazon is set to go to trial in 2026.[iv] So the sudden embrace of Trump by tech billionaires – after decades of mostly left-leaning political affiliations – may represent little more than an attempt to secure a return to light-touch antitrust enforcement for their companies.

But it is also worth noting that the anti-competitive methods employed by Standard Oil, Microsoft, Google and Amazon bear a striking resemblance to the way Donald Trump has done business — as a real estate developer and as president. They are all essentially shakedowns of the weak by the strong: the use of the stronger party’s leverage to take from the weak something that the stronger party could not have acquired by fairer means.

For Rockefeller and Gates the shakedown involved the use of leverage over third parties to punish competitors. For Google and Amazon, the shakedown is more direct. They demand business information from those who need access to their online platforms – i.e., to secure favorable positions in Google search results or Amazon Marketplace – then use that information to start competing businesses in the most promising new online markets. Then they favor their affiliated new businesses on their platforms in order to take market share away from the innovative firms whose ideas they admired.

Donald Trump’s real estate business never acquired that kind of market power, but he did routinely create economic leverage with contractors and trades people by refusing to pay them, using that leverage to “renegotiate” a better price. And as president he has secured concessions from universities, law firms and others using the leverage afforded him as head of the executive branch (and of a congressional party that he has cowed into submissiveness, for reasons explained in this space many times before).

All of these billionaires believe that their particular forms of bullying and shakedown were/are justified, and sometimes their arguments win the day. Andrew Carnegie’s U.S. Steel Corp. won its antitrust case in the Supreme Court. And despite multiple bankruptcies and hundreds of contract dispute lawsuits, Trump-the-Brand has emerged more or less intact.

Today’s tech billionaires may see in Trump someone who understands their economic bullying the way they do. Perhaps they see the world as a dog-eat-dog place where those who do not destroy their enemies will be destroyed themselves. Maybe they are simply rationalizing their massive riches in a world where so many have so much less. (The psychology of tech billionaires, and of Trump, is probably a far more complicated subject than can fit in this space.) But it remains to be seen whether their Trump sycophancy will pay off. As of this writing many of the FTC suits against tech firms remain active.

Conclusion

I don’t know the precise intended meaning of the slogan “every billionaire is a policy failure.” Perhaps it is meant as shorthand for the following logic:

- Billionaires have earned unimaginable wealth in the shelter of American legal and governmental institutions. Under that umbrella they enjoy secure property rights, the enforcement of contracts, physical security, stable capital markets (until the last few months), and clean, pleasant places to live. Some of them (Andrew Carnegie, Elon Musk and Sergei Bryn, e.g.) migrated to the U.S. from elsewhere to enjoy that stable economic environment.

- Having benefited from the economic security that our liberal democracy affords entrepreneurs, billionaires have a moral obligation to “give back” – not just through private philanthropy, but through taxes paid to the very government whose statutes, courts, police, military, and regulators provide that security.

- And because billionaires vanquish competitors along the way, others lose (economically) so that they might win. Therefore, they ought to pay much more in taxes as a share of income (or wealth, if they hide their income) to finance the services that are the foundation of their success. That is, tax rates ought to be much more progressive than they are now.

If that slogan means these things, great. I agree. If it is instead a rallying cry for the kind of intellectually sloppy attribution errors that feed feelings of contempt toward a class of people, then count me out because some of those people are allies who subscribe to all or most of the logic above.

If we still want to speak precisely and accurately about billionaires and politics, we ought to acknowledge that the picture is complicated. Many billionaires supported Kamala Harris and continue to support Democrats. Many believe the superrich should pay more in taxes. Many care about climate change and spend lavishly to try to mitigate it. If left populism morphs into something more revolutionary or anti-capitalistic than the logic contained in the numbered propositions above, those allies may no longer be allies.

Being precise and accurate isn’t inconsistent with being horrified with the current attack on our political-economic institutions, or with “fighting back.” To the contrary, it’s part of how one can fight back effectively. – David Spence

———————–

[i] For context, real GDP roughly tripled over that same period, and the value of a 1980 dollar was $3.88 in 2024.

[ii] I summarize these effects in chapter 2 of Climate of Contempt.

[iii] There are many excellent accounts of this history. I recommend those found in Ron Chernow’s Titan and Daniel Yergin’s The Prize. But Wikipedia offers a shorter version.

[iv] The FTC also brought an enforcement action against Zuckerberg’s Meta.

Advertorials, Influence, and Guilt By Association

As a couple of billionaires (or one billionaire and one pretender) run roughshod over legal standards and democratic norms, it reinforces the suspicion that economic elites get the policies that they want at the expense of the public interest. Folk wisdom says that he who pays the piper calls the tune. But as I show in Climate of Contempt, social scientists have struggled to find empirical support for that idea in politics. And the related proposition — that the United States would have stronger national climate legislation by now but for corporations’ control of the policymaking process — is also dubious.

Just about everyone condemns instances of actual political payoffs and corruption, such as the First Energy scandal in Ohio, or the spread of climate disinformation by the Heartland Institute,or Elon Musk’s efforts to gut agencies that are investigating his companies. But the natural outrage that that kind of behavior provokes sometimes leads people to infer that corruption is the norm in politics. It isn’t.

Blaming “corporations” takes people’s eyes off the prize. They focus less on stabilizing and reducing atmospheric carbon, and instead on vanquishing enemy industries or companies, or expelling them from participation in a net zero energy future.

Public discussion of oil company advertising and lobbying sometimes falls into this trap. In some social media and academic communities it is assumed that the goals of utilities and oil companies are almost always contrary to the public interest. And once you are convinced that an adversary is guided only by nefarious motives, everything that actor does can look condemnable. In that environment we can lose sight of what is truly deceitful or corrupt, on the one hand, and what is mere advocacy, advertising or lobbying, on the other.

Two websites that feed this particular contempt narrative are Amy Westervelt’s Drilled and the DeSmog Blog, both of which focus on the petroleum industry as a political bad actor. Both sites invite readers to feel contempt for oil industry, sometimes by casting innocuous behavior (as well as bad behavior) as blameworthy. A good example is their 2023 report on the industry’s relationship with news outlets, “Readers for Sale.”

That report documents the oil industry’s longstanding use of “advertorials” to try to influence public opinion about political issues, a practice that apparently continues today. I have mentioned advertorials in a previous post. They are the ads dressed up as news articles that one sees all the time on the CNN web site or the pages of the New York Times. They are usually marked as ads or “sponsored content,” but often in relatively small print, and too often without indicating up front who sponsor is. So readers skimming the headline will not learn the identity of the sponsor. And according to some studies, many people do not recognize them as ads at all.

Therefore, these arrangements between media outlets and the sponsors deserve some scorn because they are apparently deceiving some readers. So kudos to Drilled/DeSmog for providing a primer on this practice, and examples. Their report is worth reading in full for that reason.

But like an advertorial, that report can also mislead those who don’t read it, or who read it uncritically. The report opens with a description of how a Mobil Oil VP “invented” the advertorial in the 1970s,* suggesting that thereafter the practice became so commonplace that “[t]oday, almost every major media outlet offers space for corporations to run advertorials … [and] a creative team ready to write those advertorials, and create graphics, videos, and podcasts to go with it.”

Well, not exactly. In fact, a close reading of the full report reveals the various exaggerations in the report’s own summary statement. But more importantly, the report lumps together several different types of actions: (i) publishing advertorials, (ii) selling ads and advertising services, and (iii) sponsoring events. And it is a mistake to paint these three types of actions with the same broad condemnatory brush. They are different types of commercial relationships, each with its own ethical dimensions. And their differences are best illustrated using the report’s own examples from two media companies: Bloomberg News and The Economist.

The report takes Bloomberg to task for a accepting “more than $2 million in ad revenue from fossil fuel companies,” and for Michael Boomberg’s remarks at its “Qatar Economic Forum 2024,” which included positive statements about liquified natural gas and Qatar’s geopolitical significance. The report does not seem to allege any deception on the part of Michael Bloomberg or his company, but rather hypocrisy for promoting both LNG and carbon capture in ways that “contradict[] the findings of Bloomberg’s excellent roster of climate reporters.”

To support the hypocrisy allegation the report cites a November 2023 Bloomberg story on the Energy Transitions Commission, a group of corporate leaders who are doubtful about the future viability of carbon sequestration. Thus, Drilled/DeSmog ascribes to Bloomberg reporters the positions of the people who were the subjects of a Bloomberg article. Given that leap, the imputation of hypocrisy to the organization is easy. But it is misplaced, unless one assumes that those corporate leaders’ beliefs about the future will prove correct, and that Bloomberg reporters also believe those same things. Sloppy.

When it comes to accepting oil company ad revenue, the report doesn’t seem to charge Bloomberg with running advertorials — only with selling a lot of ads to oil companies. Presumably these are the sort of clearly marked ads that Bloomberg and most media outlets run for other sponsors. The authors of “Readers for Sale” do not state whether they believe that all sales of ad space to companies influences reporters’ coverage of those companies, but the implication is that the authors’ would make that inference with respect to oil companies. Of course, in the cash-strapped world of news reporting, ad revenues are an unavoidable necessity. Indeed, in the online world where consumers expect free content, ads are THE revenue model. And presumably modern consumers are more savvy consumers of advertising (not disguised as news) than previous generations were.

The report also takes both Bloomberg and The Economist to task for accepting oil company sponsorship for educational events that carry the media companies’ brand. That sort of sponsorship of an event, service or research is deceptive if the sponsorship is not disclosed. And it gives rise the the possibility that the the funder is influencing or driving the event content. For that reason, some people or organizations decline outside sponsorship in order to avoid the problem altogether. But of course, that sort of funder contamination is a possibility, not an inevitability. Some organizations or researchers may bend over backwards to avoid letting sponsorship skew their work, and err in the opposite direction.** Others may be influenced subconsciously in the direction of the funder. Many choose to disclose sponsorship and leave it to the reader to decide whether the event or research has been contaminated by the funder’s support.

The sponsored events run by The Economist (and cited in the report) were a Shell-sponsored event on the future of education, a BP-sponsored event called “Sustainability Week,” and a Chevron- and ExxonMobil-sponsored “summit” on sustainability. Readers should go to the Drilled/DeSmog report (linked above) and click the links to those cited examples. Decide for yourself if (a) there is any deception about sponsorship, or (b) whether the event seems to have been influenced by the presence of oil industry sponsors. (To my eye the latter two look like attempts by business leaders to promote conversation about sustainability; and the first one seems to be about education, not energy policy. But look for yourself.)

Some industry groups try to influence academic research through sponsorship; other times the industry’s sponsorship of research is aimed at solving an environmental problem. Recently Stanford University convened a select committee to review the oil industry sponsorship of research activities at Stanford’s new Doerr School of Sustainability. The committee issued a report recommending the addition of more “guardrails” to Stanford’s industry-funded research, but against “dissociating” from industry by banning such support. Seeing “mutual benefit” in those arrangements, the committee went further and questioned whether “dissociation based on companies’ climate transition pathways could be consistent with … Stanford’s [academic freedom policies],” … and “the University’s capacity to determine whether a company has obstructed climate policies in a manner that would justify dissociation.”

The Stanford report disappointed critics who equate sponsorship with contamination. A recent paper in a journal called WIREs argues that “universities are an established yet under-researched vehicle of climate obstruction by the fossil fuel industry.” As evidence for that conclusion the authors cite evidence of extensive financial and human connections between the industry and university research, but much less evidence demonstrating systematic bias. Still, the inference that researchers will be reluctant to bite the hand that feeds them is attractive because it is intuitive. And it would have been understandable had Stanford decided to avoid the appearance of impropriety by banning such support.

But the notion that sponsorship inevitably contaminates results is too neat, as evidenced by the fact that this issue has divided environmental NGOs for decades. The Environmental Defense Fund, for example, has cooperated with industry to study environmental problems, reasoning that it can get better data and build better studies with firms’ inside knowledge. EDF has produced a body of research on methane leakage from oil and gas operations that has proven extremely important and useful, much of it undertaken with the industry’s cooperation. In my view, it would be difficult to review EDF’s body of work in this field and call it “greenwashing,” but each reader can make their own decision about that. The same could be said for the work of the Princeton Net Zero America project and other groups who advocate for the environment but accept industry funding.

Too often complaints about industry contamination of research or reporting are tautologies, based on the assumption (as opposed to the demonstration) of bias. Rejecting industry sponsorship is a good way to avoid those suspicions, but accepting sponsorship does not confirm them. Rather, it takes investigation to demonstrate bias. And it is misleading to portray the “old energy” industries as only and always working against the public interest. It just isn’t that simple. So don’t let ad hominem arguments cheat you out of a fuller understanding of the messy complexity and unavoidable moral ambiguity of the energy transition. — David Spence

——-

*Most sources place the invention of advertorials much earlier. The use of television newspeople to advertise products was common in the 1950s. However, that practice was discontinued among network major news divisions because it allowed sponsors to capitalize upon reporters’ reputations for credibitlity and objectivity, which is the very problem the Drilled/DeSmog report raises. This sort of host advertising remains a common feature of podcasts that already have a clear ideological bent. Right wing podcasters like Charlie Kirk and Alex Jones hawk survivalist gear to their conspiracy-interested audiences. Likewise, the progressive hosts of Pod Save America endorse their sponsors’ products during the episodes — things like meal kits, bespoke tailored clothing and home security systems. Presumably that sort of thing is less misleading when the podcaster isn’t a trained journalist.

**I recall a statement I heard decades ago from an attorney whose firm was disqualified by professional responsibility rules from representing any of about 100 parties to complex litigation that involved allocating financial responsibility for cleaning up an old landfill. (Several of those 100 companies were the firm’s clients, and representation of any one would create an “appearance of impropriety” or conflict of interest.) The attorney said, perhaps facetiously, “We can’t violate that ethical rule. But these companies could never get better representation that two of our attorneys competing against one another.”

The Speech, The Censure, The Rebuttal … and the energy transition

The national GOP has taken a fairly sharp turn against green energy in the last few years, suggesting that persuading GOP politicians to support a lower-carbon energy future is unlikely in the near term. Instead, it looks like the only near term path to stronger climate policy is more Democratic Party victories in future elections. But while Democrats in Congress are united in support of the energy transition, they remain divided in other ways. And they disagree about the most likely route to future electoral successes.

A few weeks ago three items came across my news feed on the same day that illustrate this problem. One was a report on the censure of Rep. Al Green for his organized protests during President Trump’s March 3 address to Congress. The second was an article in The Atlantic describing Rep. Elise Slotkin’s approach to delivering the democratic response to that address. The third item was about the Cook Political Report’s publication of historical PVI ratings for all 50 states from 1997-2024.

Let’s take The Atlantic piece first.

The article, by Tim Alberta, is an account of how Slotkin approached the task of delivering the opposition’s remarks from the time Senate Minority Leader Charles Schumer asked her to do so until she delivered the speech on March 3d. But it is also an account of Slotkin’s enthusiastic rejection of progressive “identitarian” politics, and her focus on economic issues instead. Alberta:

Slotkin argues that the surest way to heal the country—to defuse identitarian struggles, pacify the culture wars, uncoil our hypertense politics—is by restoring the confidence of working families. When people feel assured of their financial welfare and of their children’s future, she insists, they become far less receptive to the type of strongman demagoguery that thrives on scapegoats and feasts on anxiety.

This approach sets Slotkin apart from many of her fellow Democrats, though the difference is better measured by degree than kind. She is quite familiar—as a woman, as a Jew, as the daughter of a woman who came out late in life as a lesbian—with the plight of certain constituencies within her party’s coalition. It’s simply a matter of emphasis: Slotkin sees electoral success as the path to addressing America’s injustices, not the other way around.

To my mind, Slotkin’s optimism about returning economic issues their dominant position in the minds of voters may be underestimating the power of the propaganda machine to elevate cultural divides in voters’ minds. Nevertheless, Alberta goes on to note correctly that Slotkins’ approach was unpopular with a segment of progressives:

Naturally, not everyone was thrilled with what they heard. “Slotkin’s address suffered from the same half-heartedness that has seized the Democrats since last November,” my colleague Tom Nichols wrote in The Atlantic, echoing some of the criticism online. “Her response, and the behavior of the Democrats in general, showed that they still fear being a full-throated opposition party, because they believe that they will alienate voters who will somehow be offended at them for taking a stand against Trump’s schemes.”

This is the view that “fighting back” implies a “full-throated” intensity of feeling – the same hostility, the same contempt – that the captive-of-MAGA GOP now regularly displays toward Democrats. In this framing, fighting back is as much about tone and emotional style as it is about substance. Nor is tone the only cleavage line in the party divides. Aspects of Slotkin’s background disqualified her in the eyes of influential progressive Twitter accounts, who criticized the party’s decision to have a “former CIA operative and hardcore Zionist” and “national security Karen” deliver such a “contemptible response” to Trump.

Of course, many Democrats disagreed with these assessments. (Slotkin’s remarks were short (10 minutes), and you can judge for yourself by watching them here.) But Alberta is probably correct when he describes Slotkin’s philosophy as one that “wins” in places where Democrats need to win. The article explains why Slotkin “reject[ed] all of the suggestions she received about her speech. … The problem isn’t with any of the[] particular causes [she was asked to champion], she said; the problem is that everyone seemed focused more on the people she might name in her remarks and less on the people who would be at home listening to them.”

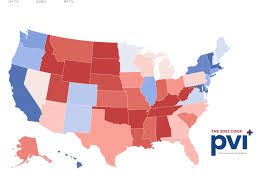

Which brings us to what the Cook PVI data tell us.

Readers of this blog or of Climate of Contempt can anticipate the story the new Cook data tell: namely, that the electoral strategies Slotkin rejected are unlikely to help Democrats win control of national policymaking institutions in the near term. Those strategies do have a logic. They are intended to move the Overton Window: i.e., to change public opinion in the long run. But in today’s information environment they are more likely to be weaponized effectively against Democrats than to help Democrats win elections in the few remaining contestable jurisdictions.

David Wasserman’s summary of the data (subscription required) hits the key points:

As recently as 2005, the states of West Virginia, Arkansas, Ohio, Missouri and Iowa performed within a few points of the nation as a whole. Today, obviously, they’ve exited stage right. The same was true back then of Oregon, Washington and Colorado, which have exited stage left. …

Just two generations ago, America was hardly geographically polarized at all at the presidential level. In the 1960 race between John F. Kennedy and Richard Nixon, there were 34 states decided by single digits and 20 states decided by fewer than five points. Fast forward to the 2024 race between Trump and Kamala Harris, and just 13 states were decided by single digits, and just eight states were decided by fewer than five points [Cook’s definition of “competitive”].

This is the same story we see in congressional elections. Crucially, the decline in competitiveness favors the GOP in presidential elections. Wasserman again:

Today, going by Cook PVI, there are 31 states totaling 312 Electoral College votes that are more GOP-leaning than the nation as a whole …. In other words, Trump performed better in these 31 states than he did in the national popular vote. …

Back in 2013, just 27 states totaling 255 Electoral votes were more GOP-leaning than the nation as a whole (23 states plus DC totaling 283 votes leaned Democratic). And in 1997, 28 states totaling 271 Electoral votes were more GOP-leaning than the nation, while 22 states plus DC totaling 267 votes leaned Democratic — virtually no skew at all.

In other words, the key to the policy future lies in the hands of small group of people in swing jurisdictions, many of whom currently vote Republican. Progressive messaging may be working to solidify support in blue states and districts, but doesn’t seem to moving the needle in the desired direction in competitive places. These data suggest that future Democratic presidential nominees may be wise to follow Elise Slotkin’s approach.

Nevertheless, some progressives willing to risk alienating moderate voters in contestable jurisdictions in the hope that it (a) activates more new voters than the voters it alienates, and (b) nudges the Overton Window in the “right” direction. They may see no downside taking this chance. It may also be that they see no important differences between Democratic Party moderates who represent contestable jurisdictions now, on the one hand, and Republicans on the other. They may view both groups as corrupted by corporate interests, despite the fact that measures of ideology put moderate Democrats much closer to progressives than to even the most moderate Republican.

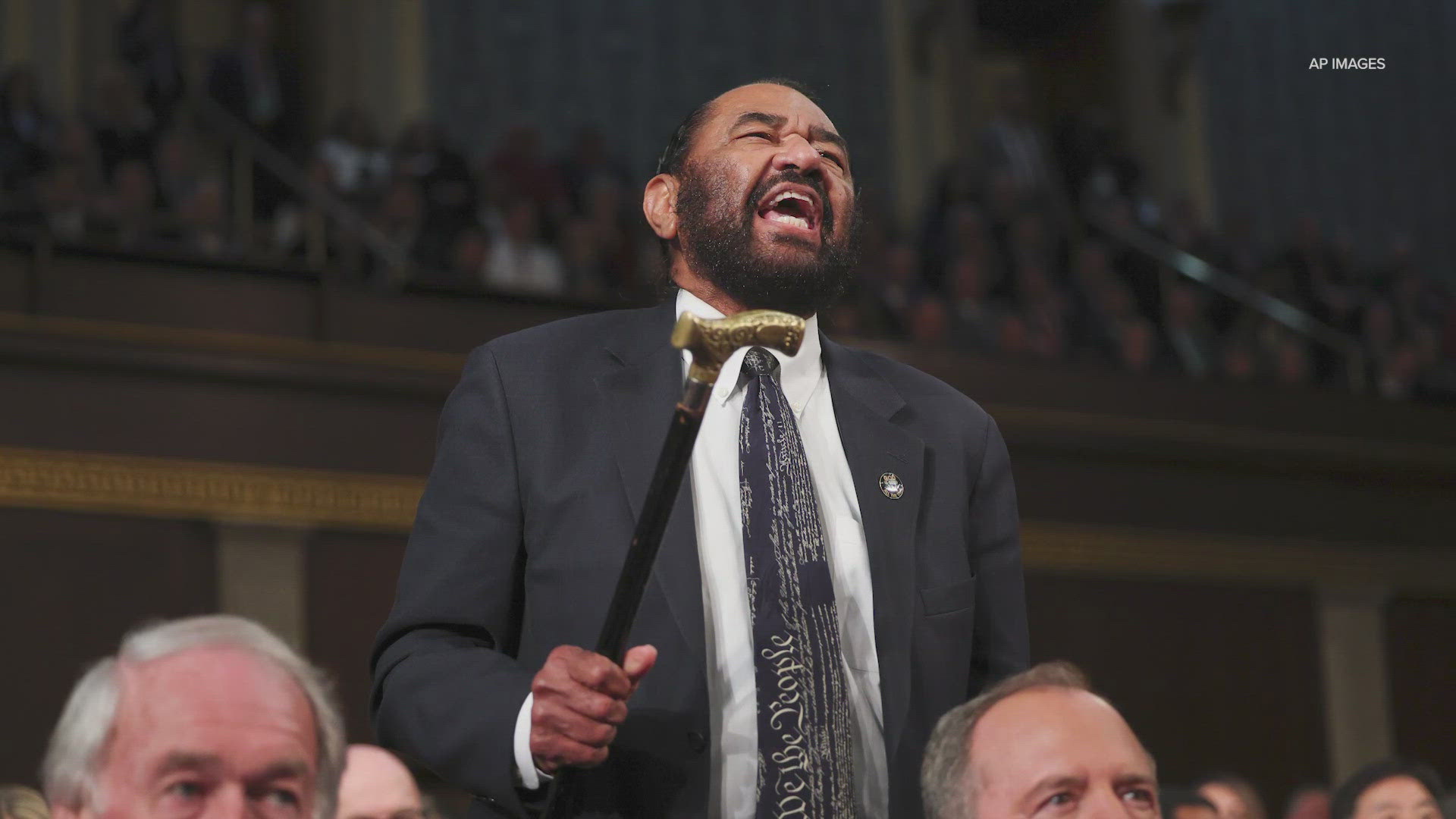

Last, consider the House vote censoring Rep. Al Green.

For those who missed the Al Green controversy, Rep. Green stood early in the president’s speech and heckled the president for a few minutes, and was eventually removed from the chamber. Two days later the House censured Green, 224-198. Tired of being alone during his chamber protest, Green successfully enlisted several of his co-partisans to oppose censure a few days later by singing the protest song “We Shall Overcome.” But in the ensuing vote Green was unable to convince House Democrats to stay together, as 10 of voted in favor of the censure.

The 10 House Democrats who supported the censure represented different types of districts from a variety of states. We don’t know why they voted the way they did; collectively, however, their districts’ Cook PVI scores average D+2.3, much more competitive than the House average. Some of the 10 may be people who feel as though they are in a bit of an electoral bind. They understand that the forces pushing politicians to the ideological extremes affect their party too. They must try to please both primary voters, who are more ideologically extreme and negatively partisan than the average party member. But the things that help elected Democrats enhance their chances of winning a primary election may hurt their chances of winning the general election in a contestable seat, and vice versa.

In competitive seats, signalling moderation and bipartisanship may make electoral sense.

Back to the Energy Transition

The second Trump Administration is making it clearer than ever that climate policy and the energy transition are partisan issues. This is not a surprise, given that the last decade has seen the departure of the most prominent climate hawks from the GOP congressional caucus. And Republican politicians who claim to value stronger climate policy rarely back up those claims with their votes. Indeed, the forthcoming votes over the repeal of the Inflation Reduction Act will show us more about those putatively pro-climate conservatives, and exactly how hard the congressional GOP will work to derail the energy transition.

Meanwhile, if stronger national climate policy requires Democratic Party victories, that, in turn, implies winning elections in places where Republicans win them now. Some Democrats have done well in those kinds of places. Perhaps the party’s national message-makers ought to listen to those people. – David Spence

How to Support the Energy Transition in Difficult Times

Every once in a while, on a whim, I decide to assemble all of the stories in my energy news feed from a single month regarding local opposition to energy transition projects — new wind farms, solar farms, transmission lines, nuclear plants, hydrogen plants, etc.. I decided to do so once again for the month of January 2025, and you can find those stories here.

The purpose of this exercise, from my point of view, is to illustrate just how common and local these NIMBY (“not in my backyard“) movements are.

NIMBY opposition is common because it has a basic logic to it. Often times local people believe they are being asked to bear the costs of an energy project without capturing enough of the benefits. Communities know that for renewable energy plants, most of the jobs will be temporary construction jobs. Some projects, like transmission lines, may bring no benefits to the local community at all. And sometimes local opposition is based on a misunderstanding of the project’s attributes, or even local resentment that a one community member is making money off the project while the rest of the community is not.

NIMBY opposition is local in that it is usually a grassroots phenomenon. Some energy transition activists dismiss opposition to clean energy projects as an “astroturf” phenomenon — that is, as the product of elite manipulation of locals. That sort of dismissal is both inaccurate and counterproductive. Even when local groups receive outside support, their core energy remains local. Rejecting that notion makes locals want to double down their opposition.

What energy transition projects need are local advocates for the project other than the project sponsors.

In chapter 5 of my book I mention several organizations that try to provide this sort of advocacy, or to assist those locals who are willing to champion energy infrastructure projects in their community. One is the Renewable Energy Legal Defense Initiative, an effort out of Columbia University that provides legal assistance in the sighting process for renewable energy projects. Another national group called Greenlight America is now providing technical and political assistance to advocates seeking to support clean energy projects in their communities. And in chapter 6 I list a number of rural clean energy organizations that provide political and technical assistance to local advocates. Perhaps the most effective and long standing of these efforts is the Rural Minnesota Energy Board, a cooperative effort of rural counties to organize and facilitate energy project siting.

The politics of local trade-offs are complicated, and they require treating locals’ concerns with understanding and respect. It is not simply a matter of sharing economic benefits with locals; it is also about listening to them and making them a part of the decision-making process. It also requires overcoming the temptation to free ride: that is, the “I support the energy transition, but you can’t build here“ temptation.

Championing a local energy transition project is perhaps the best way individuals can support the energy transition. It is far more productive than venting anger online, which in today’s media environment is more likely to become fodder for caricaturing your group than to persuade anyone to oppose the other group. — David Spence

Don’t watch, read

The poet Robert Burns once wrote, “Be merry, I advise. But as we be merry, may we also be wise.” As Republicans aim to roll back climate policy progress it is increasingly difficult for the climate coalition to be merry.

The fire hose of frightening news is by design. It is Steve Bannon’s promise to “flood the zone with shit” realized, and it is intended to stick a thumb in the eye of the Democrats, liberals and progressives who the MAGA right regards with such dripping contempt. If you are wondering why formerly thoughtful, sober congressional conservatives go along — why they support policies or unqualified nominees that they would have openly opposed a few years ago — the answer lies in the power of the modern media environment to shape voters’ views and preferences.

It would be comforting to think that the propaganda machine only distorts other people’s political views. But it is an equal opportunity warper of perceptions. It winds us up emotionally and censors the information we see — all in order to persuade us. Today, cable news hosts, pundits, podcasters — anyone who isn’t a dedicated, trained journalist serving a politically-broad audience — is trying to persuade you at least as much as they try to inform or educate you. And they do that by provoking emotion, sharing your outrage and steering it toward particular political conclusions.

When you watch or listen to news, you encounter pundits and prognosticators whose job it is to provide an opinion; they do so because it helps to fill air time. The opinion may or may not be the same opinion they would have developed away from the cameras or microphone if given more time. These people are content providers, and so they supply opinions, and do so in a hyper-competitive market for your attention — one in which provocative views get more clicks.

Reading the news is different. When you read the news you can control the rate at which you take in new information. When you read news from a trained journalist who has curated expert opinions for you, you get a much fuller picture of the facts and the context in which they sit. Reading the news is better for both sides of your brain: the emotional side and the rational side.

Passive learning is less effective than active learning, and reading is more active than watching or listening. It is better for children’s cognitive development to read a story rather than to watch the movie version of the story because it invokes their imagination. So it is with adults and information about complex policy problems like climate change.

So the problem is not just that formerly thoughtful conservative politicians must kowtow to the MAGA Republicans who vote in Republican primaries. Cable news and podcasts keep the climate coalition angry and anxious too, suggesting that talking to our GOP friends, family and neighbors about politics and policy is pointless. But it is essential to political progress.

Today it is more difficult to be merry and wise about regulatory politics than at any time in a century. But unless we all figure our how to get smarter about consuming news in the modern media environment, policy progress will elude us. — David Spence

Why my political predictions could be wrong #3 – Young people will save us.

Note: This is the third in a series of posts auditing the political analysis (and corresponding prescription) in Climate of Contempt. The first two were here and here.]

Longtime denizens of #Climate and #Energy social media communities will be familiar with the argument that it is Boomers who are standing in the way of a bolder climate policy and a more progressive politics. Some people see young Republicans’ professed support for a green energy transition (see here and here) and conclude that strong regulatory legislation will find its way through Congress when Boomers finally have exited this earth — and the voting pool.

Putting aside the attribution errors these sorts of generalizations trigger, the 2024 election cast some doubt on the blame-Boomers hypothesis. Many of the writers and pundits making the anti-Boomer argument are members of Generation X, and exit polls showed that GenX voters broke for Trump (54-45) more than Boomers (49-49) did. Still, Millennials and GenZ each broke for Harris, collectively 51-46. So the hope that young people will save climate policy is not extinguished.

Perhaps today’s young voters will turn out to be the kind of voters and political leaders who will prioritize regulating greenhouse gas emissions, either because more of them will join the Democratic Party or because more will be willing to reach across the aisle on that issue as Republicans.

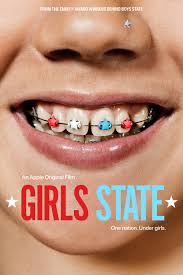

Earlier this year coverage of a new documentary film offered some support for that proposition. The film, Girls State, suggested that young people – or at least young women – might approach politics in more productive ways than their elders, offering hope for a return to a better functioning American democracy in the future. The film depicts a national summer camp on politics and governance for young women, and is a sort of sequel to the filmmakers’ earlier project, Boys State.[i] The BBC’s description of the documentary offers a flavor of the sort of hope it inspired:

One aspect [that filmmakers] Moss and McBaine did not anticipate was the nuanced nature of participants’ views on political subjects – which were often surprising. That diversity of opinions was reflected in participants such as Emily Worthmore, a conservative and daughter of a pastor who, while staunchly against abortion, believes in allowing other women to make their own choices on the matter. …

Yet one of the most refreshing elements was that those who disagreed showed compassion and respect. In one key moment, Worthmore and Cecilia Bartin, a liberal activist, have a lively yet civil debate on gun ownership. “There was a huge willingness to listen, that gave me a lot of optimism,” says McBaine.

NPR’s interview with the two filmmakers sounded similar notes:

[Interviewer Ayesha] RASCOE: What do you want the audience to take from both of these documentaries when thinking about teenagers and politics and how they grapple with issues?

[Filmmaker Jesse] MOSS: Well, I think we’re all curious about our future as a democracy. And I think these programs and these films are really tests of the proposition that we can find a kind of common ground and confront the existential problems that we have in our world and in our country. And we see, in both “Boys State” and “Girls State,” people actually trying to do politics in a healthier way than they do in the adult state. They look to listen. They look to build connections and find common ground, even around these divisive issues. They’re also not naive. They’re actually really smart and sophisticated about the world they’re sailing into, and yet they are not daunted. They are not cynical. They are really hopeful.

Those who have read chapters 3 and 4 of my book will already know why it is risky to extrapolate from the events depicted in Girls State to a real world future in which today’s teenagers inhabit positions of political leadership.

The key point is that Girls State participants need not worry about re-election. If they had to be re-elected, and they represented “safe seats” (like most members of Congress today), they would need to protect their re-election prospects by avoiding actions that displease the ideological extremists and negative partisans who vote in party primaries. Since re-election is not a concern for Girls State participants, they are free to explore solutions to complicated national problems through cross-party dialogue without worrying about accusations that they are fraternizing with the enemy.

In other words, this lack of accountability to voters allowed Girls State participants to problem solve better than members of Congress can. (Incidentally, this insulation from voter accountability is the same reason why regulatory agencies tend to produce better and more representative policy choices than Congress can.) In any case, until voters vote in ways that demand different behavior from their representatives, stronger national climate policy will probably continue to elude us. And until more of our political behavior and discussion moves offline, extremist negative partisans will continue to exert the lion’s share of influence over members of Congress.

Furthermore, younger voters’ support for Democrats last November wasn’t as strong as predicted. While young women voted Democrat at roughly the same percentages as in the recent past, young men voted Republican in larger numbers than recent presidential elections. A post-election Economist/YouGov poll indicated that 50% of 18-29 year olds have a favorable impression of the GOP, the same percentage that indicated a favorable impression of the Democrats. And young voters in swing states voted for Trump in larger numbers than in other recent elections.

So it remains to be seen how these countervailing forces will affect young voters in the future. Will the propaganda machine strengthen right populism among rural youth as it has their elders? Or will their belief in climate science withstand the propaganda onslaught? Perhaps in the coming years … as the costs of climate change hit younger GOP voters … and they see the national government turning a blind eye to those costs … and voters who already care deeply about climate change engage them in an ongoing dialogue about the issue … then perhaps national climate politics will change for the better.– David Spence

—————

[i] Boys and Girls state programs are more fully described in their Wikipedia entry here. The Boys State program has been held annually since the 1930s; Girls State is of more recent vintage. The documentary producers previously produced a film covering the Boys State national meeting.

Big Oil Urges Trump Not to Gut Climate Law

Wall Street Journal

Why Isn’t the IRA More of a Political Winner for Democrats?

Inside Climate News

Why Isn’t Harris Clobbering Trump? These 15 Swing State Voters Can Tell You

New York Times

Positive Climate Tipping Points?

Positive News

October is Crunch Time for Election Interference

New York Times

Maine’s Maverick Democrat Prepares to Wield New Power

E&E Daily (Politico)

Popular Reactions to Donald Trump’s Indictments and Trials

Gary Jacobson (UC-San Diego political scientist)

Manchin-Barrasso Permitting Bill Subject of Intense Discussions

E&E Daily (Politico)

Google AI Chatbot Prone to Produce Climate Misinformation

Center for Countering Digital Hate

8 House Democrats Join Vote to Overturn Tailpipe Rule

E&E Daily (Politico)

How China and a tariffs row cast a shadow over booming U.S. solar power

The Guardian

Union Workers Making EV Batteries Lament Partisan Divide on EVs

Inside Climate News

How Russia Uses American Political Influencers

Wired

How Swing State Politics are Sinking a Global Steel Deal

New York Times

South Carolina is Considered a Model for ‘Managed Retreat’

Inside Climate News

France’s ‘Digital Pause’

Positive News

The Energy Transition – Where are we really?

McKinsey

The New Eco-Right

USA Today

Climate change isn’t top of mind for NC voters. Here’s why.

USA Today Network

Permitting Reform and Partisan Polarization

Regulatory Review

Greens Fume Over Fossil Fuel Presence at DNC

Politico

Coal Power Defined This Minnesota Town. Can Solar Win It Over?

New York Times

American Militia and the 2024 Election